Brihadisvara Temple

| Brihadisvara Temple | |

|---|---|

தஞ்சைப் பெருவுடையார் கோயில் | |

Brihadishvara Temple complex | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Hinduism |

| District | Thanjavur district |

| Deity | Shiva |

| Festivals | Maha Shivaratri |

| Location | |

| Location | Thanjavur |

| State | Tamil Nadu |

| Country | India |

| Geographic coordinates | 10°46′58″N 79°07′54″E / 10.78278°N 79.13167°E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Chola architecture |

| Creator | Rajaraja I |

| Completed | 1010 CE[1][2] |

| Inscriptions | Tamil |

| Elevation | 66 m (217 ft) |

| Official name | The Brihadisvara Temple complex, Thanjavur |

| Part of | Great Living Chola Temples |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (iii) |

| Reference | 250bis-001 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| Extensions | 2004 |

| Area | 18.07 ha (44.7 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 9.58 ha (23.7 acres) |

Brihadishvara Temple, called Rajarajesvaram (lit. 'Lord of Rajaraja') by its builder, and known locally as Thanjai Periya Kovil (lit. 'Thanjavur Big Temple') and Peruvudaiyar Kovil, is a Shaivite[3][4] Hindu temple built in a Chola architectural style[5] located on the south bank of the Cauvery river in Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India.[1][6] It is one of the largest Hindu temples and an exemplar of Tamil architecture.[7] It is also called Dakshina Meru (Meru of the South).[8] Built by Chola emperor Rajaraja I between 1003 and 1010 CE, the temple is a part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the "Great Living Chola Temples", along with the Chola-era Gangaikonda Cholapuram temple and Airavatesvara temple, which are about 70 kilometres (43 mi) and 40 kilometres (25 mi) to its northeast respectively.[9]

The original monuments of this 11th-century temple were built around a moat. It included gopura, the main temple, its massive tower, inscriptions, frescoes, and sculptures predominantly related to Shaivism, but also of Vaishnavism and Shaktism. The temple was damaged in its history and some artwork is now missing. Additional mandapam and monuments were added in the centuries that followed. The temple now stands amidst fortified walls that were added after the 16th century.[10][11]

Built using granite, the vimana tower above the shrine is one of the tallest in South India.[6] The temple has a massive colonnaded prakara (corridor) and one of the largest Shiva lingas in India.[6][9][12] It is also famed for the quality of its sculpture, as well as being the location that commissioned the brass Nataraja, Shiva as the lord of dance, in the 11th century. The complex includes shrines for Nandi, Parvati, Murugan, Ganesha, Sabhapati, Dakshinamurti, Chandeshvara, Varahi, Thiyagarajar of Thiruvarur, Siddhar Karuvoorar and others.[9][13] The temple is one of the most visited tourist attractions in Tamil Nadu.[14]

Nomenclature

Rajaraja Chola, who commissioned the temple, called it Rajarajeshvaram (Rajarājeśvaram), literally "the temple of the god of Rajaraja".[15] A later inscription in the Brihannayaki shrine calls the temple's deity Periya Udaiya Nayanar, which appears to be the source of the modern names Brihadisvara and Peruvudaiyar Kovil.[16]

Location

The Peruvudaiyar Temple[17] is located in the city of Thanjavur, about 350 kilometres (220 mi) southwest of Chennai. The city is connected daily to other major cities by the network of Indian Railways, Tamil Nadu bus services and the National Highways 67, 45C, 226 and 226 Extn.[18][19] The nearest airport with regular services is Tiruchirappalli International Airport (IATA: TRZ), about 55 kilometres (34 mi) away.[20]

The city and the temple though inland, are at the start of the Kaveri River delta, thus with access to the Bay of Bengal and through it to the Indian Ocean. Along with the temples, the Tamil people completed the first major irrigation network in the 11th century for agriculture, for movement of goods and to control the water flow through the urban center.[21]

History

A spectrum of dravidian temple styles continued to develop from the fifth to the ninth century over the Chalukya era rule as evidenced in Aihole, Badami and Pattadakal, and then with the Pallava era as witnessed at Mamallapuram and other monuments. Thereafter, between 850 and 1280, Cholas emerged as the dominant dynasty.[2][22] The early Chola period saw a greater emphasis on securing their geopolitical boundaries and less emphasis on architecture. In the tenth century, within the Chola empire emerged features such as the multifaceted columns with projecting square capitals. This, states George Michell, signaled the start of the new Chola style.[2][note 1] This South Indian style is most fully realized both in scale and detail in the Brihadeshwara temple built between 1003 and 1010 by the Chola king Rajaraja I.[1][2]

Additions, renovations and repairs

The main temple along with its gopurams is from the early 11th century. The temple also saw additions, renovations, and repairs over the next 1,000 years. The raids and wars, particularly between Muslim Sultans who controlled Madurai and Hindu kings who controlled Thanjavur caused damage.[11][note 2] These were repaired by Hindu dynasties that regained control. In some cases, the rulers attempted to renovate the temple with faded paintings, by ordering new murals on top of the older ones. In other cases, they sponsored the addition of shrines. The significant shrines of Kartikeya (Murugan), Parvati (Amman) and Nandi are from the 16th and 17th-century Nayaka era.[11][26] Similarly the Dakshinamurti shrine was built later.[26] It was well maintained by Marathas of Thanjavur.

Description

Architecture

The Peruvudaiyar temple's plan and development utilizes the axial and symmetrical geometry rules.[27] It is classified as Perunkoil (also called Madakkoil), a big temple built on a higher platform of a natural or man-made mounds.[28] The temple complex is a rectangle that is almost two stacked squares, covering 240.79 metres (790.0 ft) east to west, and 121.92 metres (400.0 ft) north to south. In this space are five main sections: the sanctum with the towering superstructure (sri vimana), the Nandi hall in front (Nandi-mandapam) and in between these the main community hall (mukhamandapam), the great gathering hall (mahamandapam) and the pavilion that connects the great hall with the sanctum (Antrala).[29]

The temple complex integrates a large pillared and covered veranda (prakara) in its spacious courtyard, with a perimeter of about 450 metres (1,480 ft) for circumambulation. Outside this pillared veranda there are two walls of enclosure, the outer one being defensive and added in 1777 by the French colonial forces with gun-holes with the temple serving as an arsenal. They made the outer wall high, isolating the temple complex area. On its east end is the original main gopuram or gateway that is barrel vaulted. It is less than half the size of the main temple's vimana. Additional structures were added to the original temple after the 11th century, such as a mandapa in its northeast corner and additional gopurams (gateways) on its perimeters to allow people to enter and leave from multiple locations.[29][30] Some of the shrines and structures were added during the Pandya, Nayaka, Vijayanagara and Maratha era, before the colonial era started, and these builders respected the original plans and symmetry rules. Inside the original temple courtyard, along with the main sanctum and Nandi-mandapam are two major shrines, one for Kartikeya and for Parvati. The complex has additional smaller shrines.[29][31][32]

The Peruvudaiyar temple continued the Hindu temple traditions of South India by adopting architectural and decorative elements, but its scale significantly exceeded the temples constructed before the 11th century. The Chola era architects and artisans innovated the expertise to scale up and build, particularly with heavy stone and to accomplish the 63.4 metres (208 ft) high towering vimana.[29][31]

The temple faces east, and once had a water moat around it. This has been filled up. The fortified wall now runs around this moat. The two walls have ornate gateways called the gopurams. These are made from stone and display entablature. The main gateways are on the east side. The first one is called the Keralantakan tiruvasal, which means the "sacred gate of the Keralantakan". The word Keralantakan was the surname of king Rajaraja who built it. About a 100 metres (330 ft) ahead is the inner courtyard gopuram called the Rajarajan tiruvasal. This is more decorated than the Keralantakan tiruvasal, such as with its adhishthanam relief work narrating scenes from the Puranas and other Hindu texts.[29] The inner eastern gopuram leads to a vast courtyard, in which the shrines are all signed to east–west and north-west cardinal directions. The complex can be entered either on one axis through a five-story gopuram or with a second access directly to the huge main quadrangle through a smaller free-standing gopuram. The gopuram of the main entrance is 30 m high, smaller than the vimana.[13] The main temple-related monuments and the great tower is in the middle of this courtyard.[29] Around the main temple that is dedicated to Shiva, are smaller shrines, most of which are aligned axially. These are dedicated to his consort Parvati, his sons Murugan and Ganesha, Nandi, Varahi, Karuvur deva (the guru of Rajaraja Chola), Chandeshvara and Nataraja.[13] The Nandi mandapam has a monolithic seated bull facing the sanctum. In between them are stairs leading to a columned porch and community gathering hall, then an inner mandapa connecting to the pradakshina patha, or circumambulation path. The Nandi (bull) facing the mukh-mandapam weighs about 25 tonnes.[33] It is made of a single stone and is about 2 m in height, 6 m in length and 2.5 m in width. The image of Nandi is a monolithic one and is one of the largest in the country.[34]

Preservation & Restoration

As a world heritage monument, the temple and the premises comes under the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) which falls under the Ministry of Culture of the Government of India, to ensure safety, preservation and restoration. The surrounding facilities have been upgraded to create an ambience worthy of the grandeur of this ancient marvel with lighting, signage and facilities for devotees and visitors. The lighting of the monument is designed to enhance the natural color of the stone along with the sculptural forms adorning all corners of the temple. The restoration has been undertaken by the Archaeological Survey of India that commissioned Sheila Sri Prakash Indian architect and designer to lead the design.[35]

Sanctum and the Sri-vimana

The sanctum is at the center of the western square. It is surrounded by massive walls that are divided into levels by sharply cut sculptures and pilasters providing deep bays and recesses. Each side of the sanctuary has a bay with iconography.[36][27] The interior of the sanctum sanctorum hosts an image of the primary deity, Shiva, in the form of a huge stone linga. It is called Karuvarai, a Tamil word that means "womb chamber". This space is called garbha griha in other parts of India. Only priests are allowed to enter this inner-most chamber.[37]

In the Tamizhan style, the sanctum takes the form of a miniature vimana. It has the inner wall together with the outer wall creating a path around the sanctum for circumambulation (pradakshina). The entrance is highly decorated. The inside chamber is the sanctum sanctorum, which houses the brihad linga.[2]

The main Vimana (Shikhara) is a massive 16 storeys tower of which 13 are tapering squares. It dominates the main quadrangle. It sits above a 30.18 metres (99.0 ft) sided square.[36] The tower is elaborately articulated with Pilaster, piers (a raised structure), and attached columns which are placed rhythmically covering every surface of the vimana.[38]

Deities and Natya Sastra dance mudras

The temple is dedicated to Shiva in the form of a huge linga, his abstract aniconic representation. It is 29 feet (8.7 m) high, occupying two storeys of the sanctum.[6][12] It is one of the largest monolithic linga sculptures in India.[34]

| North side | South side |

| Bhairava (Shiva) | Ganesha |

| Mahishasuramardini (Durga) | Vishnu |

| Saraswati | Gajalakshmi |

The Shaivism temple celebrates all major Hindu traditions by including the primary deities of the Vaishnavism and Shaktism tradition in the great mandapa of the main temple. The distribution of the deities is generally symmetric, except for the east entrance side which provide for the door and walkway. In addition to the main deities, each side provides for dvarapalas (guardians), and various other sculptures. The vestibule has three stone sculptures that is intricately carved, and mural paintings.[40] The ground floor level sanctum walls have the following sculptures:[40]

- East wall: Lingodbhava, standing Shiva, Pashupata-murti, plus two dvarapalas flanking the pathway from ardha-mandapam

- South wall: Bhikshatana, Virabhadra, Dakshinamurti, Kalantaka, Nataraja[note 3] plus two dvarapalas

- West wall: Harihara (half Shiva, half Vishnu), Lingodbhava, Chandrashekhara without prabhavali, Chandrashekhara with prabhavali, plus two dvarapalas

- North wall: Ardhanarishvara (half Shiva, half Parvati), Gangadhara without Parvati, Pashupata-murti, Shiva-alingana-murti, plus two dvarapalas

On the second floor, Shiva's Tripurantaka form in different postures is depicted corresponding to these sculptures. Above these floors, the sri-vimana towers above in thirteen storeys (talas). Above these storeys is a single square block of granite weight 80 tons, and 7.77 metres (25.5 ft) side. On top of this block, at its corners are Nandi pairs each about 1.98 metres (6 ft 6 in) by 1.68 metres (5 ft 6 in) in dimension. Above the center of this granite block rises the griva, the sikhara and the finial (stupi) of Tamil Hindu temple architecture. This stupi is 3.81 metres (12.5 ft) in height, and was originally covered with gold (no longer). The sikhara at the top is cupola-shaped and weighs 25 tons.[40][41] Each storey of this tower is decorated with kutas and salas. The shrinking squares tower architecture of this temple differs from the tower at the Chola temple at Gangaikondasolisvaram, because this is straight in contrast to the latter which is curvilinear. The temple's sri-vimana magnitude has made it a towering landmark for the city.[40] The upper storey corridor wall of the aditala is carved with 81 of the 108 dance karanas – postures of Natya Sastra. This text is the basis of the Bharathanatyam, the classical dance of Tamil Nadu. The 27 unrepresented karanas are blank blocks of stone, and it is unclear why these were not carved. The 81 postures carved suggest the significance of this classical Indian dance form by early 11th century.[12]

The garbhagriha is square and sits on a plinth. This is moulded and 0.5 metres (1 ft 8 in) thick. It consists of upapitham and adhishthanam, respectively 140 cm and 360 cm thick.[12]

Mandapa

The two mandapa, namely maha-mandapa and mukha-mandapa, are square plan structures axially aligned between the sanctum and the Nandi mandapa. The maha-mandapa has six pillars on each side.[42] This too has artwork. The Vitankar and Rajaraja I bronze are here, but these were added much later. The maha-mandapa is flanked by two giant stone dvarapalas. It is linked to the mukha-mandapa by stairs. The entrance of the mukha-mandapa also has dvarapalas. With the mandapa are eight small shrines for dikpalas, or guardian deities of each direction such as Agni, Indra, Varuna, Kubera and others. These were installed during the rule of Chola king Rajendra I.[42]

Inscriptions indicate that this area also had other iconography from major Hindu traditions during the Chola era, but these are now missing. The original eight shrines included those for Surya (the sun god), Saptamatrikas (seven mothers), Ganesha, Murugan, Jyeshtha, Chandra (the moon god), Chandeshvara and Bhairava.[42] Similarly, in the western wall cella was a massive granite Ganesha built during Rajaraja I era, but who is now found in the tiruch-churru-maligai (southern veranda). Of the Shaktism tradition's seven mothers, only Varahi survives in a broken form. Her remnants are now found in a small modern era brick "Varahi shrine" in the southern side of the courtyard. The original version of the others along with their original Chola shrines are missing.[42]

Murals

The temple has an underneath layer of Chola frescoes on the sanctum walls along the circumambulatory pathway. These frescoes which cover floor to ceiling, were discovered in 1931 by S. K. Govindasami of the Annamalai University.[43] The painters used natural pigments and infused it into the wet limestone layer as it was setting in. The Chola frescoes were largely of Shaivism themes. These were restored in the 2000s.[44] The total Chola fresco area is about 670 square metres (7,200 sq ft), of which about 112 square metres (1,210 sq ft) had been uncovered as of 2010 in a method that preserves both paintings, a technique developed by Archaeological Survey of India.[43] The frescoes narrate Hindu mythology.[43][45] According to Balasubrahmanyam, most frescoes are related to Shiva, but the 11th century Chola frescoes also show Vishnu, Durga and others, as well as scenes of Chola royalty, courtly and common life.[45]

The later constructions, additions and modifications to the temple curtailed the amount of natural light inside the temple. The frescoes were thus photographed in a limited way and interpreted. According to Sriraman, a complete imaging with better photographic equipment suggests that these historic interpretations were incorrect.[43] For example, a fresco that was previously interpreted as Dakshinamurti Shiva is actually a secular scene of a royal guru meditating under a banyan tree. On the tree are shown peacocks, birds, monkeys, squirrels and owls, plus a cobra. The animals and birds are shown as worried of the cobra, the ones closer to the snake are shown to be more worried.[43] Other parts of the panel similarly show a court listening to a saint. Other show women in different dresses in different dance mudra.[43]

Some of the paintings in the sanctum sanctorum and the walls in the passage had been damaged because of the soot that had deposited on them once upon a time. Owing to the continuous exposure to smoke and soot from the lamps and burning of camphor in the sanctum sanctorum over a period of centuries certain parts of the Chola paintings on the circumambulatory passage walls had been badly damaged.[44] The Archaeological Survey of India, for the first time in the world, used its unique de-stucco process to restore 16 Nayak paintings, which were superimposed on 1000-year-old Chola frescoes.[44] These 400-year-old paintings have been mounted on fibre glass boards, displayed at a separate pavilion.[44]

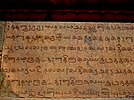

Inscriptions

The temple walls have numerous inscriptions in Tamil and Grantha scripts. Many of these begin with customary Sanskrit and Tamil language historical introduction to the king who authorized it, and predominant number of them discuss gifts to the temple or temple personnel, in some cases residents of the city.[46][47] The temple complex has sixty four inscriptions of Rajaraja Chola I, twenty nine inscriptions of Rajendra Chola I, one each of Vikrama Chola, Kulottunga I and Rajamahendra (Rajendra II), three of a probable Pandyan king, two of Nayaka rulers namely, Achyutappa Nayaka and Mallapa Nayaka.[48]

Temple personnel

An inscription on the north wall of enclosure, dated 1011 CE, gives a detailed accounts of people employed and supported by the temple. The inscription gives their wages, roles and names. It includes over 600 names including those of priests, lamp lighters, washermen, tailors, jewelers, potters, carpenters, sacred parasol bearers, dance gurus, dancing girls, singers, male and female musicians, superintendents of performance artists, accountants among others. Their wages was in parcels of land, so their temple employment was likely part-time.[47][49]

The temple employed devadasis who were dancers and singers of devotional hymns. Among its numerous inscriptions are frequent gifts that state, "to provide for worship, for food to assembly of sannyasis (monks or ascetics) and for repairs". According to George Michell, the Thanjavur temple was a major charity institution in its history. It provides free meal for pilgrims, devotees and wayfarers on a daily basis. On the days of Hindu festivals, these meals were elaborate and when brahmins were particularly invited and fed.[47][49]

Millennium commemoration

Built in the year 1010 CE by Chola emperor Rajaraja I in Thanjavur, the temple is popularly known as the Big Temple. It turned 1,000 years old in September 2010. To celebrate the 1000th year of the grand structure, the state government and the town held many cultural events. It was to recall the 275th day of his 25th regal year (1010 CE) when Rajaraja I (985–1014 CE) handed over a gold-plated kalasam (copper pot or finial) for the final consecration to crown the vimana, the 59.82-metre tall tower above the sanctum.[50][51][52]

Bharathanatyam Yajna

To mark the occasion, the state government organised a Bharathanatyam Yajna, classical dance show under noted dancer Padma Subramaniam. It was jointly organised by the Association of Bharatanatyam Artistes of India (ABHAI) and the Brhan Natyanjali Trust, Thanjavur. To mark the 1000th anniversary of the building, 1,000 dancers from New Delhi, Mumbai, Pune, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Singapore, Malaysia and the US danced in concert to the recorded 11 verses of divine music Thiruvisaippa (ninth volume of Thirumurai) composed by Karuvur deva (the guru of Rajaraja). The small town turned into a cultural hub for two days beginning 26 September 2010 as street performers and dancers performed throughout the town.[53][54]

Commemorative stamps and coins

On 26 September 2010 (Big Temple's fifth day of millennium celebrations), as a recognition of Big Temple's contribution to the country's cultural, architectural, epigraphical history, a special ₹ 5 postage stamp featuring the 66 metres (216 ft) tall giant Raja Gopuram was released by India Post.

The Reserve Bank of India commemorated the event by releasing a ₹ 5 coin with the model of temple embossed on it.[55][56] A Raja, Cabinet Minister of Communications and Information Technology released the esteemed Brihadeeswarar temple special stamp, the first of which was received by G K Vasan, Cabinet Minister of Shipping.

Mumbai Mint issued Rs 1,000 Commemorative Coin with the same picture as on the Rs 5 coin. It was the first 1,000 Rupees coin to be released in the Republic of India coinage. This coin was a Non Circulative Legal Tender (NCLT).[57]

On 1 April 1954, the Reserve Bank of India released a ₹ 1,000 currency note featuring a panoramic view of the Brihadeeswar temple marking its cultural heritage and significance. In 1975, the then government led by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi demonetised all ₹ 1,000 currency notes in an effort to curtail black money. These notes are now popular among collectors.[58]

In 2010, the then Tamil Nadu chief minister, M Karunanidhi renamed Semmai Rice, a type of high productivity paddy variant, as Raja Rajan-1,000 to mark the millennial year of the constructor of the temple, Rajaraja Chola.[59]

Reception

The temple "testifies the brilliant achievements of the Chola in architecture, sculpture, painting and bronze casting".[60] The temple finds mention in many of the contemporary works of the period like Muvar Ula and Kalingathuparani. According to Chatterjee, the Dravidian architecture attained its supreme form of expression in the temple and it successor, the Brihadeeswarar Temple, Gangaikonda Cholapuram.[61] The temple has been declared as a heritage monument by the Government of India and administered by the Archaeological Survey of India as a protected monument. The temple is one of the most visited tourist attractions in Tamil Nadu.[14]

The temple was declared as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, along with the Brihadeeswara Temple at Gangaikondacholapuram and Airavatesvara temple at Darasuram that are referred as the Great Living Chola Temples.[9] These three temples have similarities, but each has unique design and sculptural elements.[62] All of the three temples were built by the Cholas between the 10th and 12th centuries CE and they have continued to be supported and used by Hindus. The temples are classified as "Great Living" as the temples are active in cultural, pilgrimage and worship practises in modern times.[63]

Cultural events

The Brihadishvara temple at Thanjavur is the site of annual dance festivals around February, around the Mahashivratri. Major classical Indian dance form artists, as well as regional teams, perform their repertoire at this Brahan Natyanjali festival over 10 days.[64]

Car festival

The Temple car was rolled out on its trial run from opposite to Sri Ramar temple on 20 April 2015 witnessed by a large number of people.[65] Nine days later, the maiden procession of the temple car was held. This was the first such procession in this temple held in the past hundred years, according to news reports.[66]

Novels

Kalki Krishnamurthy, a renowned Tamil novelist, has written a historical novel named Ponniyin Selvan, based on the life of Rajaraja.[67] Balakumaran, another Tamil author has written a novel named Udaiyar themed on the life of Rajaraja I and the construction of the temple.[68]

Administration

The temple is currently administered and managed by Babaji Bhonsle, the head of the Thanjavur Maratha royal family. He serves as the hereditary trustee of the palace Devasthanam which continues to manage 88 Chola temples including the Brihadeeswara temple. Tamil groups have been unsuccessfully petitioning the Tamil Nadu government to revoke these rights as he is not of Chola or Tamil lineage. According to one of the protesters, who also happens to be the coordinator of the Big Temple Rights Retrieval Committee, Babaji Bhonsle is also not the legal heir of the Maratha kings of Thanjavur.[69]

Gallery

The temple features many sculptures, reliefs and murals:[70]

-

Brihadisvara Temple, Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India

-

An elephant relief on the Brihadisvara Temple, Thanjavur

-

Shiva with a begging bowl as a saddhu (monk, Bhikshatana)

-

Ardhanarishvara (half Shiva, half Parvati) symbolizing that the male and female principles are inseparable[71]

-

Ganesha is depicted both in the main temple and a separate shrine.

-

Separate Ganesha shrine with temple corridor in the back

-

Subrahmanyar shrine in the north part of the courtyard. Also called "Murugan", "Kartikeya" or "Skanda".

-

Chandeshvara shrine. On right is the wall of main temple, in back the eastern gopuram. Chandeshvara is a meditating yogi and Nayanmar Bhakti movement saint.

-

Lakshmi statue, a Vaishnava sculpture reverentially displayed

-

Gaja-lakshmi mural, another Vaishnavism themed artwork

-

Vishnu sculpture at the Shaivism temple

-

A yoga and meditation relief; the temple portrays numerous secular and saint scenes.

-

Krishna playing prank on gopikas by hiding on the tree, with their clothes

-

Nandi shrine

-

Sculpture

-

Vimana outer wall detail

-

Reliefs adorning the stairs

-

Relief detail

-

Relief detail

-

Entrance

-

Vimana view

-

Left profile view

-

The view at night

-

Early hours at Tanjore Periya Koil

-

A yoga and meditation relief

-

Tamil inscriptions at Brihadisvara Temple

See also

- Penneswaraar Temple

- Thanjavur Chariot festival

- Raja Raja Chola I

- Chola Dynasty

- List of largest monoliths

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

- Great Living Chola Temples

Notes

- ^ Douglas Barrett in his 1975 publication on Chola architecture states that a new style emerged between 866 and 940 CE starting with Vijayalaya, the first Chola ruler. According to Barrett, the Chola style did not develop out of the Pallava tradition.[23] According to Gary J. Schwindler, Barrett's work supplies opinions that are "opportunities for endless conjecture and debate".[24]

- ^ Thanjavur was a target of both Muslim and Hindu neighbouring kingdoms, both near and far. The Madurai Sultanate was established in the 14th century, after the disastrous invasions and plunder of South India by Ala ud-Din Khalji's armies of Delhi Sultanate led by Malik Kafur.[25] Later Adil Shahi Sultanate, Qutb Shahis, Randaula Khan and others from east and west coasts of South India raided it, and some occupied it for a few years.[11]

- ^ In Tamil literature, the lord of dance form of Shiva, is referred to as Adavallan or Kuttaperumanadigal. This bronze style Nataraja from the Chola era is much celebrated and studied, including those of later texts such as Unmaivilakkam and Citampara Mummani Kovia describing its significance. Nataraja in Indian art dates to earlier pre-Chola centuries.[39]

References

- ^ a b c d Thanjavur Archived 7 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ a b c d e f Michell 1988, pp. 145–148

- ^ Rajaraja the Great: A Garland of Tributes. Department of Museums, Government Museum. 1984. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ India Perspectives. PTI for the Ministry of External Affairs. 1995. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Rao, Raghunadha (1989). Indian Heritage and Culture. Sterling Publishers. p. 32. ISBN 9788120709300. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d "The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI)". Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ Keay, John (2000). India, a History. New York, United States: Harper Collins Publishers. pp. xix. ISBN 0-00-638784-5. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ K. V. Raman. Temple Art, Icons And Culture Of India And South-East Asia. Sharada Publishing House, 2006. p. 136.

- ^ a b c d "Great Living Chola Temples". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2004. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, pp. 1–21.

- ^ a b c d George Michell (2008), Architecture and Art of Southern India, Cambridge University Press, pages 16-21, 89-91

- ^ a b c d S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, pp. 16–29.

- ^ a b Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 185.

- ^ D. Raphael (1996). Temples of Tamil Nadu, Works of Art. Ratnamala. p. 9. ISBN 978-955-9440-00-0. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ S. R. Balasubrahmanyam (1975). Middle Chola Temples: Rajaraja I to Kulottunga I, A.D. 985-1070. Thomson. p. 87. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ "Brihadeeswara Temple". Brihadeeswara Temple. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "NH wise Details of NH in respect of Stretches entrusted to NHAI" (PDF). Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India. National Highways Authority of India. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ "Thanjavur bus routes". Municipality of Thanjavur. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ Ē. Kē Cēṣāttiri (2008). Sri Brihadisvara: The Great Temple of Thānjavūr. Nile. p. 5.

- ^ Marshall M. Bouton (2014). Agrarian Radicalism in South India. Princeton University Press. pp. 72–78. ISBN 978-1-4008-5784-5.

- ^ S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Douglas E. Barrett (1974). Early Cola Architecture and Sculpture; 866-1014 A.D. Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-10507-6. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ Schwindler, Gary J. (1977). "Review: Early Cola Architecture and Sculpture". The Journal of Asian Studies. 36 (4). Cambridge University Press: 705. doi:10.2307/2054437. JSTOR 2054437. S2CID 163896079.

- ^ George Michell (2008), Architecture and Art of Southern India, Cambridge University Press, pages 9-13, 16-21

- ^ a b S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Thapar 2004, pp.43, 52–53

- ^ Reddy, G.Venkatramana (2010). Alayam - The Hindu temple - An epitome of Hindu Culture. Mylapore, Chennai: Sri Ramakrishna Math. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-7823-542-4.

- ^ a b c d e f S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, pp. 16–19.

- ^ Winand M. Callewaert (1995). Gods and Temples in South India. Manohar. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-81-7304-107-5. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ a b Tanjavur: Brhadisvara temple, The monument and the living tradition Archived 30 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Kapila Vatsyayan and R Nagaswamy et al, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, Government of India (2012), page 7

- ^ Branfoot, Crispin (2008). "Imperial Frontiers: Building Sacred Space in Sixteenth-Century South India". The Art Bulletin. 90 (2): 185. doi:10.1080/00043079.2008.10786389. JSTOR 20619601. S2CID 154135978.

- ^ S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, p. 22, Quote: "It is 3.65 m high, 5.94 m long and 2.59 m broad, estimated to weigh 25 tons.".

- ^ a b V., Meena (1974). Temples in South India (1st ed.). Kanniyakumari: Harikumar Arts. pp. 23–24.

- ^ "Architecture is Ultimately about People". Architecture Construction & Engineering Update Magazine. 18 February 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, pp. 17–19.

- ^ "Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent – Glossary". Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2007.

- ^ Ching 2007, pp. 338–339

- ^ a b Padma Kaimal (1999), Shiva Nataraja: Shifting Meanings of an Icon Archived 28 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 81, No. 3, pages 394-395, Figure 3 on page 392

- ^ a b c d e S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, pp. 18–21.

- ^ "Great Living Chola Temples". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, pp. 22–25.

- ^ a b c d e f PS Sriraman (2010), Digital photo documentation of murals at Brihadisvara Temple, Tanjavur: a tool for art historians in Space, Time, Place (Editors: Stefano Campana et al), pages 167-172

- ^ a b c d "ASI restores 400-year-old paintings". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 28 February 2010. Archived from the original on 17 November 2004. Retrieved 22 June 2010.; Another report about Chola frescoes[dead link]

- ^ a b S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, pp. 29–36.

- ^ S.R. Balasubrahmanyam 1975, pp. 15, 25, 53 with footnotes.

- ^ a b c PV Jagadisa Ayyar (1993), South Indian Shrines, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 81-206-0151-3, pages 411-423

- ^ C. Sivaramamurti. The Great Chola Temples: Thanjavur, Gangaikondacholapuram, Darasuram. Archaeological Survey of India, 2007 - Architecture, Chola - 96 pages. p. 26.

- ^ a b Michell 1988, pp. 59–60.

- ^ BBC News augue (25 September 2010). "India's Big Temple marks 1,000th birthday". Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ PS. R. Balasubrahmanyam (1971), Orient Longman Publications, Early Chola temples:Parantaka I to Rajaraja I, 907–985 A.D

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Ananthacharya Indological Research Institute (1984), Rāja Rāja, the great:seminar proceedings

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Rediff News. "India's Biggest Temple turns 1000-years". Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ Subramanian, T. S. (1 August 2010). "A grand dance spectacle at the Thanjavur Big Temple". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 4 August 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ Deccan Herald (26 September 2010). "Stamp, coin release mark 1,000 years of Big Temple". Archived from the original on 6 October 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Release of a special postal stamp and a five- rupee coin". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 27 September 2010. Archived from the original on 29 September 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ "Release of Commemorative Coin" (PDF). 3 July 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Express Buzz, The Indian Express (26 September 2010). "INR 1000 note of 1954 popular in Tanjavur". Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ MSN News (26 September 2010). "Semmai Paddy as "Raja Rajan-1000"". Retrieved 27 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)[permanent dead link] - ^ "Great Living Chola Temples". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- ^ Roma Chatterjee, ed. (2016). India Art and Architecture in ancient and medieval periods. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 32. ISBN 978-81-230-2080-8.

- ^ Ayyar, P.V. Jagadisa (1993). South Indian Shrines. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 316. ISBN 81-206-0151-3.

- ^ Srinivasan, Pankaja (4 June 2012). "Inside the Chola Temple". The Hindu. Coimbatore. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ Brahan Natyanjali Archived 29 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu

- ^ Trial run of Big Temple car, Rolls; out after 100 years; maiden run on April 29 Archived 19 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Hindu, 21 April 2015

- ^ Big temple chariot festival held after 100 years Archived 19 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Hindu, 30 April 2015

- ^ A., Srivathsan (19 October 2011). "Age hardly withers charm of Ponniyin Selvan". The Hindu. Chennai. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Special Coin to Remember Rajendra Chola". Express News Service. Chennai: The New Indian Express. 4 February 2014. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Tamil groups want Maratha hold over Thanjavur Big Temple to go". Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ C. Sivaramamurti (1977). L'Art en Inde. H. N. Abrams. pp. 287–288, 427. ISBN 978-0-8109-0630-3.

- ^ "Ardhanārīśvara". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2011. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

Bibliography

- Prasanna Kumar Acharya (2010). An encyclopaedia of Hindu architecture. Oxford University Press (Republished by Motilal Banarsidass). ISBN 978-81-7536-534-6.

- Prasanna Kumar Acharya (1997). A Dictionary of Hindu Architecture: Treating of Sanskrit Architectural Terms with Illustrative Quotations. Oxford University Press (Reprinted in 1997 by Motilal Banarsidass). ISBN 978-81-7536-113-3. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Vinayak Bharne; Krupali Krusche (2014). Rediscovering the Hindu Temple: The Sacred Architecture and Urbanism of India. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-6734-4. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- S.R. Balasubrahmanyam (1975), Middle Chola Temples, Thomson Press, ISBN 978-9060236079

- Ching, Francis D.K. (2007). A Global History of Architecture. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 338–339. ISBN 978-0-471-26892-5.

- Alice Boner (1990). Principles of Composition in Hindu Sculpture: Cave Temple Period. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0705-1. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Alice Boner; Sadāśiva Rath Śarmā (2005). Silpa Prakasa. Brill Academic (Reprinted by Motilal Banarsidass). ISBN 978-8120820524. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- A.K. Coomaraswamy; Michael W. Meister (1995). Essays in Architectural Theory. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. ISBN 978-0-19-563805-9. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Dehejia, V. (1997). Indian Art. Phaidon: London. ISBN 0-7148-3496-3.

- Adam Hardy (1995). Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-312-0. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Adam Hardy (2007). The Temple Architecture of India. Wiley. ISBN 978-0470028278. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Adam Hardy (2015). Theory and Practice of Temple Architecture in Medieval India: Bhoja's Samarāṅgaṇasūtradhāra and the Bhojpur Line Drawings. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. ISBN 978-93-81406-41-0. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Monica Juneja (2001). Architecture in Medieval India: Forms, Contexts, Histories. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-8178242286. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Stella Kramrisch (1976). The Hindu Temple Volume 1. Motilal Banarsidass (Reprinted 1946 Princeton University Press). ISBN 978-81-208-0223-0. Archived from the original on 10 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Stella Kramrisch (1979). The Hindu Temple Volume 2. Motilal Banarsidass (Reprinted 1946 Princeton University Press). ISBN 978-81-208-0224-7.

- Michael W. Meister; Madhusudan Dhaky (1986). Encyclopaedia of Indian temple architecture. American Institute of Indian Studies. ISBN 978-0-8122-7992-4. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- George Michell (2000). Hindu Art and Architecture. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20337-8.

- Michell, George (1988), The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-53230-5

- Man, John (1999). Atlas of the Year 1000. United Kingdom: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-7946-0011-5. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Thapar, Binda (2004). Introduction to Indian Architecture. Singapore: Periplus Editions. pp. 43, 52–53. ISBN 0-7946-0011-5.

- T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Ajay J. Sinha (2000). Imagining Architects: Creativity in the Religious Monuments of India. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-684-5. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Burton Stein (1978). South Indian Temples. Vikas. ISBN 978-0706904499. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Burton Stein (1989). The New Cambridge History of India: Vijayanagara. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26693-2. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Burton Stein; David Arnold (2010). A History of India. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Kapila Vatsyayan (1997). The Square and the Circle of the Indian Arts. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-362-5. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

External links

- Tanjavur Brihadisvara Temple, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, Government of India

- Brihadeeswara Temple, Tamil Nadu tourism

- Dakshina Meru: The Brihadeswara Temple, Government of India

- Photos on art-and-archaeology web site

- Unesco Great Living Chola Temples