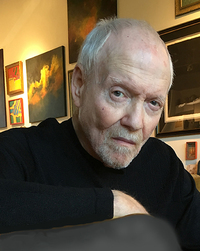

Daniel Quinn

Daniel Clarence Quinn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 11, 1935[1] Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died | February 17, 2018 (aged 82) Houston, Texas, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Website | |

| ishmael | |

Daniel Clarence Quinn (October 11, 1935 – February 17, 2018)[2] was an American author (primarily, novelist and fabulist),[3] cultural critic,[4] and publisher of educational texts, best known for his novel Ishmael, which won the Turner Tomorrow Fellowship Award in 1991 and was published the following year. Quinn's ideas are popularly associated with environmentalism, though he criticized this term for portraying the environment as separate from human life, thus creating a false dichotomy.[5] Instead, Quinn referred to his philosophy as "new tribalism".[6]

Biography

[edit]Daniel Quinn was born in Omaha, Nebraska, where he graduated from Creighton Preparatory School. He went on to study at Saint Louis University, at the University of Vienna, Austria, through IES Abroad, and at Loyola University, receiving a bachelor's degree in English cum laude in 1957. He delayed part of this university education, however, while a postulant at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Bardstown, Kentucky, where he hoped to become a Trappist monk;[7] however his spiritual director, Thomas Merton, prematurely ended Quinn's postulancy. Quinn went into publishing, abandoned his Catholic faith, and married twice unsuccessfully,[8] before marrying Rennie MacKay Quinn, his third and final wife of 42 years.[9]

In 1975, Quinn left his career as a publisher to become a freelance writer. He is best known for his book Ishmael (1992), which won the Turner Tomorrow Fellowship Award in 1991. Several judges disputed giving the entire $500,000 award to Quinn for Ishmael, rather than dividing the money among several authors, though judge Ray Bradbury, for one, supported the decision.[10] Ishmael became the first of a loose trilogy of novels by Quinn, including The Story of B and My Ishmael, all of which brought increasing fame to Quinn throughout the 1990s. He became a well-known author to followers of the environmental, simple living, and anarchist movements, although he did not strongly self-identify with any of these.[11]

Quinn traveled widely to lecture and discuss his books. While response to Ishmael was mostly very positive, Quinn's ideas have inspired the most controversy with a claim mentioned in Ishmael but made much more forcefully in The Story of B's Appendix that the total human population grows and shrinks according to food availability and with the catastrophic real-world conclusions he draws from this.[12]

In 1998, Quinn collaborated with environmental biologist Alan D. Thornhill in producing Food Production and Population Growth, a video elaborating in-depth the science behind the ideas he describes in his fiction.[13]

Quinn's book Tales of Adam was released in 2005 after a long bankruptcy scuffle with its initial publisher. It is designed to be a look through the animist's eyes in seven short tales; Quinn first explores the idea of animism as the original worldwide religion and as his own dogma-free belief system in The Story of B and his autobiography, Providence: The Story of a Fifty-Year Vision Quest.[7]

In February 2018, Quinn died of aspiration pneumonia in hospice care.[9]

Philosophy and themes

[edit]Daniel Quinn was largely a fiction writer who explored the culturally-biased world-view ("mythology", in his terms) driving modern civilization and the destruction of the natural world.[14] He sought to recognize and criticize some of civilization's most unchallenged "myths" or memes, which he considered to include the following: that the Earth was made especially for humans, so humans are destined to conquer and rule it; that humans are innately and inevitably flawed;[11][15] that humans are separate from and superior to nature (which Quinn called "the most dangerous idea in existence");[16] and that all humans must be made to live according to some one right way.[17]

Other common themes included ecology, environmental ethics, culture, and an in-depth look at human population dynamics. Although Quinn himself regarded the following associations as coincidental, his philosophy is sometimes compared with deep ecology, dark-green environmentalism, or anarcho-primitivism.[11][16][18]

Quinn notably claimed that the total population of humans, like all living things, grows and shrinks according to a basic ecological law: an increase in food availability for any population yields an accompanying increase in the population's overall size.[19] Quinn worried that popular cultural thinking ignores this reality, instead regarding civilized humans as separate from and above any such law.[11] He identified the Neolithic Revolution as the start of human overpopulation, when civilized peoples began to practice an imperialistic world-view that denigrates nature and that relies entirely upon expansionist farming ("totalitarian agriculture"),[20] the human population growing in proportion to the decline of the rest of the world's biomass.[11]

Quinn's warnings about population, especially in relation to food availability, have often been compared to the warnings of 19th-century economist Thomas Robert Malthus.[21] However, while Malthus warned that excess human population precariously motivates an excess of food production in order to sustain that population, Quinn considered the priorities of this assessment backwards. He instead warned that excess population is the inevitable result of access to excess food for the human organism en masse just as surely as it is for any other species, a concept which he described as one of the "ABCs" of well-established ecology, professing that no ecologist argues with the law (inevitable growth in the face of food availability) except in the case of the human, which he stated was universally regarded an exceptionalism despite "10,000 years of evidence" to the contrary in the form of the history of human population growth coincident with the rise of agriculture and the mass production of foodstuffs in excess to the needs for survival.

According to Quinn, the success of this totalitarian style of agriculture is unsustainable because we "kill all of our competitors for food" and even kill our "competitors once-removed" by attacking all of our favorite food species' competitors or predators, which he described as "practically holy work for our farmers: kill everything that you can't eat. Kill everything that eats what you eat.", and so on, which he claimed is causing the catastrophic loss of biodiversity planetwide, and, just as directly, an overshoot towards an eventual population crash, of which the civilized mainstream shows very little anticipation or interest.[22][23]

Quinn's conclusions on population also imply the controversial notion that sustained food aid to starving nations is merely delaying and dramatically worsening massive starvation crises, rather than resolving such crises, as is commonly assumed. Quinn claimed that reconnecting people to the food made available through their local habitats is a proven way to avoid famines and accompanying starvation. Some have interpreted this to mean that Quinn was resolving to let starving people in impoverished nations continue starving.[24][25]

Quinn described civilization as primarily a single global economy and culture, whose total dependence on agriculture requires ever-more expansion, in turn generating ever-more population growth[26] (an escalating vicious cycle he identifies as the "food race").[12] As a result, he viewed modern civilization, by definition, as unsustainable.[26] He commonly analyzed and defended the effectiveness of traditional indigenous tribal societies—regarded by anthropological research as fairly egalitarian, ecologically well-adapted, and socially secure[27] —as role models for developing a new diversity of workable human social structures in the future.[28]

Quinn self-admittedly avoided presenting simplistic or universal solutions,[29] though he strongly encouraged a worldwide paradigm shift away from the self-destructive memes of civilization and towards the values and organizational structures of a "new tribalism". He clarified that this did not refer to the old style of ethnic tribalism so much as new groupings of individuals as equals trying to make a living communally, while still subject to evolution by natural selection.[30] He eventually named this hypothetical, gradual shift the "New Tribal Revolution". Quinn cautioned that his admiration for the sustainable lifestyles of indigenous tribes is not intended to encourage a massive "return" to hunting and gathering. Rather, he intended merely to acknowledge the enormous history of relative ecological harmony between humans and the rest of the environment (from which humans are never separate) and embrace the basic unit of a tribe as an effective model for human societies (just as the pack works for wolves, the hive for bees, etc.).[27][29]

Quinn was influential in developing a vocabulary for his philosophy; he coined or popularized a variety of terms, including the following:

- Takers and Leavers — "Takers" refers to members of the dominant globalized civilization and its culture, while "Leavers" refers to members of the countless other non-civilized cultures existing both in the past and currently.[14][20][31] Quinn later regretted these terms, supposing that "hierarchical" and "tribal," respectively, may be better alternatives.[32]

- Mother Culture – a personification of any culture's inherently biased influences that are not perceived as biased by its members[33]

- Food Race – the phenomenon of ongoing human overpopulation and its accompanying global catastrophes, in which the giving of more food to starving, growing populations paradoxically yields only still greater population growth and starvation[12][34]

- Law of limited competition – a biological law that "defines the limits of competition in the community of life," according to which "you may compete to the full extent of your capabilities, but you may not hunt down your competitors or destroy their food or deny them... access to food in general," meaning across-the-board;[35] species that violate this law end up extinct

- Law of Life – the universal collection of all evolutionarily stable strategies

- Totalitarian Agriculture – today's dominant form of agriculture that "subordinates all other life-forms to the relentless, single-minded production of human food," unsustainable because it generates enormous food supplies that in turn generate ever-greater human population booms[20]

- The Great Forgetting – widespread historical ignorance regarding "the fact that we [humans] are a biological species in a community of biological species and are not exempt or exemptible from the forces that shape all life on this planet; this also includes our forgetting of the fact that most of human history has been based on an ecologically sound way of life (largely hunting and gathering)"[36]

- Boiling frog – "a metaphor for so many circumstances in life when people are unwilling or unable to react effectively to crises that occur very gradually or imperceptibly,"[37] used especially by Quinn to refer to creeping normality in terms of escalating environmental degradation

- New Tribal Revolution – a hypothetical, sociocultural period of global change that Quinn supports, in which civilization would gradually begin to transform into a collection of more sustainable, tribally-organized societies[6]

Food race

[edit]Quinn coined the term food race (by analogy to the Cold War's "nuclear arms race") to describe his concept of a perpetually escalating crisis of growing human population due to growing food production, of which the former is fueled by the latter. Quinn argues that as the worldwide human population increases, the typical international response is to produce and distribute more food to feed these greater numbers of people. However, assuming that population increases according to increased food availability, Quinn argues that this response only ends up leading to an even larger population and thus greater starvation in the end. Quinn's solution to the food race—to stop producing so much food—is not generally a common-sense or intuitive response; instead he claims he is counter-intuitive or "outside-the-box" thinking.[38][39][40]

Russell Hopfenberg has written at least two papers attempting to prove Quinn's ideas, one paper with David Pimentel titled Human Population Numbers as a Function of Food Supply[41] and Human Carrying Capacity is Determined by Food Availability.[42] Hopfenberg has also made a narrated slide show titled World Food and Human Population Growth.

Basis

[edit]Quinn bases the food race on the premise that the total human population, like that of other animals, is influenced by food supply. Thus, larger populations are the result of more abundant food supplies, and intensification of food cultivation in response to population growth merely leads to still more population growth. Quinn compared this to the arms race in the Cold War. Like Garrett Hardin, Quinn believes any development to address food security will only lead to catastrophe.[citation needed]

Comparison to Malthusian catastrophe

[edit]The similarities between this concept and a Malthusian catastrophe are obvious, but Quinn states there are certain key differences. The primary problem in a Malthusian catastrophe is a population growing faster than the growth in food supply. Quinn states that population is a function of food supply, and not merely some independent variable. Quinn considers that problem is not a scarcity of food, but, rather, overpopulation. Quinn characterizes the Malthusian problem as "how are we going to FEED all these people?", and characterizes the "Quinnian problem" as "how are we going to stop PRODUCING all these people?"[43]

Criticism

[edit]The idea that human population is tied to food supply is contentious, however. Many biologists[who?] disagree with Quinn's assessment. While food supply certainly imposes an upper limit on population growth, they point out that culture, living standards, human intelligence, and free will can impose lower, secondary limits to population growth. Critics also point out that the most significant population growth is occurring in the developing world, where regional food production is lowest. Meanwhile, the First World, where food is most plentiful, is undergoing a decline in birth rates. Quinn has suggested this results from international food distribution, claiming that the farms of the First World fuel population growth elsewhere. United Nations projections that the world population will level off sometime in the near future also contradict Quinn's statements. In 1998 Daniel Quinn and Alan D. Thornhill then of the Society for Conservation Biology made a video exploring these topics titled Food Production And Population Growth.[citation needed]

Influence

[edit]Ishmael directly inspired the 1998 Pearl Jam album Yield (and particularly the song "Do the Evolution"),[44] and the Chicano Batman song "The Taker Story" on their 2017 album Freedom is Free.[45] In 2019 The Mammals, a folk band including Mike Merenda & Ruth Ungar, released Nonet with many of the songs on it inspired by Ishmael and other Quinn books, most especially Beyond Civilization.[46] North Carolina's vegan hardcore band Undying has been heavily influenced by the work of Daniel Quinn.[47]

Quinn's writings have also influenced the filmmaker Tom Shadyac (who featured Quinn in the documentary I Am); the entrepreneur Ray C. Anderson, founder of Interface, Inc. (the world's largest manufacturer of modular carpet), who began transforming Interface with more green initiatives;[48] as well as some of the ideology behind the 1999 drama film Instinct,[3] and the 2007 documentary film What A Way To Go: Life at the End of Empire. Playwright Derek Ahonen has cited Quinn as the foremost influence on his play, The Pied Pipers of The Lower East Side, which attempts to dramatize the philosophies of New Tribalism.[49]

Actor Morgan Freeman's interest in the Ishmael trilogy inspired his involvement with nature documentaries, such as Island of Lemurs: Madagascar and Born to Be Wild, both of which he narrated, while adopting from Quinn the phrase "the tyranny of agriculture".[50][51] Punk rock band Rise Against includes Ishmael on their album The Sufferer & the Witness' reading list,[52] and its sequel, My Ishmael, inspired the name of the band Animals as Leaders.[53]

Bibliography

[edit]- (1982) The Book of the Damned Part One, Part Two and Part Three Hard Rain Press, PO Box 5495, Santa Fe, NM 87502 ISBN 9781499149999

- (1988) Dreamer CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform ISBN 9781481850063

- (1992) Ishmael, Bantam, ISBN 0553375407

- (1996) The Story of B, Bantam, ISBN 0553379011

- (1996) Providence: The Story of a 50 Year Vision Quest (autobiography), Bantam, ISBN 0553375490

- (1997) My Ishmael, Bantam, ISBN 0553379658

- (1997) A Newcomer's Guide to the Afterlife (with Tom Whalen), Bantam, ISBN 0553379798

- (1999) An Animist Testament (audio cassette of Quinn reading The Tales of Adam and The Book of the Damned)

- (2000) Beyond Civilization, Broadway Books, ISBN 0609805363

- (2001) The Man Who Grew Young (graphic novel with Tim Eldred), Context, ISBN 1893956172

- (2001) After Dachau, Steerforth, ISBN 1581952155

- (2002) The Holy, Steerforth, ISBN 1581952147

- (2005) Tales of Adam, Steerforth, ISBN 1586420747

- (2006) Work, Work, Work, Steerforth, ISBN

- (2007) If They Give You Lined Paper, Write Sideways, Steerforth, ISBN 1586421263

- (2010) Moral Ground: Ethical Action for a Planet in Peril. (chapter) Nelson, Michael P. and Kathleen Dean Moore (eds.). Trinity University Press, ISBN 9781595340665

- (2012) At Woomeroo, CreateSpace, ISBN 1477599975

- (2014) The Invisibility of Success, CreateSpace, ISBN 1494930935

- (2014) The Teachings, CreateSpace, ISBN 1502356155

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Von Ruff n.d.

- ^ n+1 2018.

- ^ a b Wilson (2007:70)

- ^ Quinn 2007.

- ^ Quinn 2002.

- ^ a b Bei Dawei (2014:53)

- ^ a b Bei Dawei (2014:46)

- ^ Quinn (Providence, 1996:107)

- ^ a b "In Memory of Daniel Clarence Quinn". Legacy. Neptune Society. 2018.

- ^ McDowell 1991.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor (2010:78–79)

- ^ a b c Bei Dawei (2014:44)

- ^ [1] Moral Ground. Trinity University Press. 2010. (Wayback Machine Archive, May 23 2016)

- ^ a b Gorman (2012:201–2)

- ^ Burr (2007:36–38)

- ^ a b Seed (2005)

- ^ Burr (2007:37–38)

- ^ Zellen, Barry (2008), Breaking the Ice. From Land Claims to Tribal Sovereignty in the Arctic, Lexington Books, 2008, pg. 331

- ^ Foung (2002:91)

- ^ a b c Burr (2007:24–5)

- ^ Ishmael.org n.d.

- ^ Bei Dawei (2014:45)

- ^ Godesky, Jason (2005). "Thesis #4: Human population is a function of food supply Archived June 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." The Anthropik Network. Rewild.info.

- ^ Ishmael.org 2013a.

- ^ Ishmael.org 2013b.

- ^ a b Experiencing Globalization: Religion in Contemporary Contexts. Derrick M. Nault, Bei Dawei, Evangelos Voulgarakis, Rab Paterson, Cesar Andres-Miguel Suva (eds). Anthem Press. 2014. p. 12.

- ^ a b Frank, Adam. "Is Civilization a Bad Idea?" NPR, 2011.

- ^ Bei Dawei (2014:49)

- ^ a b Bei Dawei (2014:52)

- ^ Rehling, Petra (2012) "Enemy metaphors and the countdown for mankind in the American TV series Space: Above and Beyond (1995–1996) and Battlestar Galactica (2003–2009)", in Jordan J. Copeland (ed.), The Projected and Prophetic: Humanity in Cyberculture, Cyberspace and Science Fiction. Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press, 145-152; PDF version: p. 7 Archived May 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Foung (2002:94)

- ^ FFF 2018.

- ^ Burr (2007:33–4)

- ^ Burr (2007:48)

- ^ Bei Dawei (2014:55)

- ^ Burr (2007:30–1)

- ^ Day, Lori. "Republicans and the Parable of the Boiling Frog", TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc., 2013.

- ^ Quinn, Daniel, and Alan D. Thornhill. "Food Production and Population Growth." Video documentary supported by the Foundation for Contemporary Theology. Houston: New Tribal Ventures (1998).

- ^ "Controlled food supply could stop overpopulation". Carrie Gazarish. Daily Kent Stater, Volume 32, Number 52, Kent State University.

- ^ "Food Production and Population Growth". Daniel Quinn, Alan D. Thornhill, PhD. Ecofuture. Population and Sustainability Media, Non-fiction.

- ^ "Human population numbers as a function of food supply" (PDF). Russell Hopfenberg (1 Duke University, Durham, NC, USA;)* and David Pimentel (2 Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA). Environment, development and sustainability 3.1: 1-15.

- ^ Russel Hopfenberg. "Human Carrying Capacity is Determined by Food Availability" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ "Q and A #83". Ishmael.org. Archived from the original on September 1, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ Anderson, Stacey. "Do the Evolution: 5 Insights From Ovation's Pearl Jam Doc." Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone, 2014.

- ^ Brown, August (2017). [www.latimes.com/entertainment/music/la-et-ms-chicano-batman-20170223-story.html Chicano Batman takes on the 800-pound gorilla with 'Freedom Is Free']. Los Angeles Times.

- ^ More information and the backstories behind these songs can be found in the Inspired section on the Ishmael website.

- ^ Times, Hardcore (January 26, 2001). "Undying". HARDCORE TIMES. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ Hart, Craig. Climate Change and the Private Sector. Routledge, 2013. p. 174.

- ^ Webster, Andy (August 7, 2009). "Bohemians: Endangered but Not Extinct". The New York Times.

- ^ "Interview: Morgan Freeman on Narrating Born to be Wild", Coming Soon. CRAVEONLINE MEDIA, LLC, 2011.

- ^ Triplett, Gene. "Morgan Freeman narrates new documentary on dwindling lemur population", News OK. News OK (The Oklahoman), 2014.

- ^ Busteed, Sheila (2007). "The state of the nation: Rise Against frontman talks about war, education and the modern role model Archived September 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine". PlugInMusic.

- ^ Chopik, Ivan (2010). "Tosin Abasi Interview". Guitar Messenger. Guitar Messenger.

Works cited

[edit]- Bei Dawei (2014), "Chapter 3: Daniel Quinn on Religion: Saving the World through Anti-Globalism?", Experiencing Globalization: Religion in Contemporary Contexts, Anthem Press

- "The Blaze". n+1. March 9, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- Burr, Chuck (2007), Culturequake: The Restoration Revolution, Trafford Publishing, ISBN 978-142511043-7

- FFF (March 30, 2018), Daniel Quinn interviewed to What a Way to Go: Life at the End of Empire, archived from the original on January 24, 2019, retrieved March 5, 2019 – via YouTube

- Foung, Mira (2002), "Chapter 4: Genetic Trespassing and Environmental Ethics", Ethical Issues in Biotechnology, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, ISBN 978-074257875-3

- Gorman, Michael, E. (2012), Transforming Nature: Ethics, Invention and Discovery, Springer Science & Business Media, pp. 201–2, ISBN 978-146155657-2

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McDowell, Edwin (June 5, 1991). "Judges in Turner Award Dispute Merits of Novel Given a $500,000 Prize". The New York Times. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- "Q and A #23". Ishmael.org. 2013a. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013.

- "Q and A #767". Ishmael.org. 2013b. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013.

- "Q and A #83". Ishmael.org. Archived from the original on September 1, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- Quinn, Daniel (1992), Ishmael, New York: Bantam Books

- Quinn, Daniel (1997), The Story of B, New York: Bantam Books

- Quinn, Daniel (1999), Beyond Civilization, New York: Three Rivers Press

- Quinn, Daniel (March 7, 2002). "The New Renaissance". Archived from the original on January 19, 2012.

- Quinn, Daniel (2007). "Schooling: The Hidden Agenda". Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

Recently I was introduced to an audience as a cultural critic, and I think this probably says it best.

- Seed, John (Spring 2005), "The Ecological Self", EarthLight Magazine #53, vol. 14, no. 4

- Taylor, Bron (2010), Dark Green Religion: Nature, Spirituality, and the Planetary Future, University of California Press, pp. 78–9, ISBN 978-052023775-9

- Von Ruff, Al. "Daniel Quinn bibliography". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- Wilson, Staci Layne (2007), Animal Movies Guide, USA: Running Free Press, p. 70, ISBN 978-096751853-4

Further reading

[edit]- "A Cybernetic View of Biological Growth: The Maia Hypothesis" (PDF). Tony Stebbing. American Journal of Human Biology 23:826–830 (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011.

External links

[edit]- Ishmael.org – The Ishmael community, Daniel Quinn's official website

- The Friends of Ishmael Society

- Read Ishmael – a website devoted to encouraging people to read Ishmael

- Ishthink.org – thinking about Ishmael

- Archived videos on YouTube

- Daniel Quinn at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Daniel Quinn

- 1935 births

- 2018 deaths

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American novelists

- American male non-fiction writers

- American male novelists

- American male short story writers

- American memoirists

- American short story writers

- Environmental fiction writers

- Writers from Omaha, Nebraska

- Food and the environment

- Human overpopulation