Dark Horse (George Harrison album)

| Dark Horse | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 9 December 1974 | |||

| Recorded | November 1973, April 1974, August–October 1974 | |||

| Studio | ||||

| Genre | Rock | |||

| Length | 41:19 | |||

| Label | Apple | |||

| Producer | George Harrison | |||

| George Harrison chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Dark Horse | ||||

| ||||

Dark Horse is the fifth studio album by the English rock musician George Harrison. It was released on Apple Records in December 1974 as the follow-up to Living in the Material World. Although keenly anticipated on release, Dark Horse is associated with the controversial North American tour that Harrison staged with Indian classical musician Ravi Shankar in November and December that year. This was the first US tour by a member of the Beatles since 1966, and the public's nostalgia for the band, together with Harrison contracting laryngitis during rehearsals and choosing to feature Shankar so heavily in the programme, resulted in scathing concert reviews from some influential music critics.

Harrison wrote and recorded Dark Horse during an extended period of upheaval in his personal life. The songs focus on Harrison's split with his first wife, Pattie Boyd, and his temporary withdrawal from the spiritual certainties of his previous work. Throughout this time, he dedicated much of his energy to setting up Dark Horse Records and working with the label's first signings, Shankar and the group Splinter, at the expense of his own music. Author Simon Leng refers to the album as "a musical soap opera, cataloguing rock-life antics, marital strife, lost friendships, and self-doubt".[1]

Dark Horse features an array of guest musicians – including Tom Scott, Billy Preston, Willie Weeks, Andy Newmark, Jim Keltner, Ringo Starr, Gary Wright and Ron Wood. It showed Harrison moving towards the funk and soul music genres,[2] and produced the hit singles "Dark Horse" and "Ding Dong, Ding Dong". Further to the criticism of his demeanour during the tour, the album was not well received by the majority of critics at the time. It peaked at number 4 on Billboard's albums chart in the US and placed inside the top ten in some European countries, but became Harrison's first post-Beatles solo album not to chart in Britain. The cover was designed by Tom Wilkes and consists of a school photograph from Harrison's time at the Liverpool Institute superimposed onto a Himalayan landscape. The album was reissued in remastered form in 2014 as part of the Apple Years 1968–75 Harrison box set.

Background

[edit]I've just been busy working. I was busy being deposed [by Allen Klein] ... I've been doing some tracks of my own, I did the Splinter album, finished up Ravi's album, went to India for two months, organized the Music Festival from India which has just completed a tour of Europe – a million things.[3]

– George Harrison, October 1974

George Harrison's third studio album since the Beatles' break-up came at the end of what he describes in his 1980 autobiography, I, Me, Mine, as "a bad domestic year".[4] From the middle of 1973, with his marriage to Pattie Boyd all but over, Harrison immersed himself in his work,[5] particularly on helping the two acts he would eventually sign to his new record label, Dark Horse Records − Ravi Shankar and a hitherto unknown group called Splinter.[6] Business issues related to the Beatles' company Apple Corps were also coming to a head during 1973–74.[7] Harrison, John Lennon and Ringo Starr became embroiled in litigation with former manager Allen Klein,[8][9] whose removal from Apple helped to conclude the suit launched by Paul McCartney in December 1970 to dissolve the band as a legal partnership.[10] The simultaneous winding down of Apple Corps' subsidiaries left several music and film projects in jeopardy.[11] Having decided to form his own label, Harrison now sought a record company to distribute Shankar's Shankar Family & Friends album, most of which was recorded in California in April 1973,[12][13] and Splinter's debut, The Place I Love.[14] Another venture that was affected was the feature film Little Malcolm.[15][16] As executive producer of this Apple Films project, Harrison was working to seal a distribution deal in Europe.[17]

Compounding the pressure, Harrison was drinking heavily and had returned to his drug-taking ways of the 1960s.[5][18] In I, Me, Mine, he refers to this as "the naughty period, 1973–74".[19][nb 1] Wounded by Harrison's frequent infidelities, Boyd had an affair with Ron Wood of the Faces[22] before eventually leaving Harrison for his friend Eric Clapton[18] in July 1974.[23][24] Both of these dalliances receive attention on Dark Horse, which author Simon Leng likens to a "musical soap opera".[25] For his part, Harrison had taken up with Starr's wife, Maureen Starkey,[26][27] and with Wood's wife Krissy.[22][28] In November 1973, Wood encouraged press speculation about Harrison's marriage by stating that "my romance with Patti is definitely on";[29] over the following year, rumours circulated about Harrison's dalliance with Starkey[30] and the UK tabloids became aware of his affair with model Kathy Simmons,[31] a former girlfriend of Wood's bandmate Rod Stewart.[32] Shortly before Dark Horse's release, Harrison avoided reporters' questions regarding his private life with a suggestion that people wait for the new album, saying, "It's like Peyton Place."[33][34][nb 2]

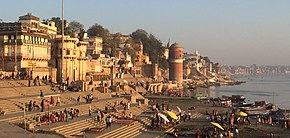

In January 1974,[37] Harrison escaped his domestic problems by visiting India[38] for two months.[3] He attended a ceremony for the opening of Shankar's new home in Benares, where they forged a plan for Harrison to sponsor an Indian classical-music concert tour of Europe, known as Ravi Shankar's Music Festival from India, and for Harrison and Shankar to then tour North America together at the end of the year.[39] Featuring up to eighteen musicians on a wide range of traditional Indian instruments,[40] the Music Festival from India was the realisation of a long-held dream for Harrison.[41] As with his dedication to Splinter's career, however, it distracted him from focusing on his own album.[42][43]

By May, Harrison had agreed distribution terms with A&M Records and was able to formally launch Dark Horse Records.[44] He remained contracted to Apple as a solo artist, like the other former Beatles, until January 1976.[45][46] After announcing the staging of the Music Festival from India in September,[47] Harrison confirmed that he planned to tour North America during November and December,[13] to promote the new record label.[48] Despite his stated aversion to performing live,[18][49] he thereby became the first member of the Beatles to tour the United States and Canada since the group's 1966 visit.[50] Since the band and its individual members were still widely revered in the US,[30][51] this resulted in considerable expectations and additional pressure on Harrison.[52][53][54][nb 3]

Songs

[edit]According to author Ian Inglis, Harrison's approach to Dark Horse was informed by a combination of despondency over the disarray and infidelities that characterised his personal life, and confusion at the criticism his 1973 album Living in the Material World received from some reviewers.[59] In Britain especially, these critics objected to the spiritual discipline espoused by Harrison and the album's pious message.[60] Although the lyrics to "Dark Horse" invite interpretation as a response to his detractors or to Boyd,[61] Harrison said he wrote the song in reference to gossip about someone who carries out clandestine sexual relationships.[62][63] In addition to supplying the name for his record company,[64] the title references Harrison's emergence as the dark horse among the Beatles, particularly in his unexpected ascendancy as a solo artist to surpass Lennon and McCartney.[65][nb 4]

Harrison conveyed his feelings on his and Boyd's inevitable split in "So Sad", which he began writing in 1972[68][69] and first recorded for Living in the Material World.[70] Leng considers the song to be the antithesis of Harrison's 1969 composition "Here Comes the Sun" in its use of stark winter imagery, reflecting "the temporary death of George's Krishna dream".[71] Harrison's inspiration for "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" came from inscriptions at his Friar Park home,[72] a legacy of the property's original owner, the eccentric Victorian lawyer and horticulturalist Frank Crisp.[73][74] Harrison said that the song's exhortation to ring out the "old" and the "false", and instead ring in the "new" and the "true", was a message everybody "in a rut" should apply to their lives when celebrating New Year.[75][nb 5]

[Dark Horse is a] remarkably revealing album ... It's a musical soap opera, cataloguing rock-life antics, marital strife, lost friendships, and self-doubt. For someone who didn't like living his life in public, Harrison was doing it with a vengeance here. Any voyeur who wanted to know the intimate details of his personal life didn't need to buy National Enquirer, they just needed to hear this disc.[1]

– Author Simon Leng, 2006

He wrote "Simply Shady" during his stay in India.[78] In a marked departure from the spiritual certainties of Harrison's previous work as a solo artist,[79] the lyrics address the karmic consequences of his wayward behaviour[80] and detail his reliance on drugs and alcohol.[81] By contrast, his and Shankar's visit to the Hindu holy city of Vrindavan inspired the devotional "It Is 'He' (Jai Sri Krishna)".[82][83] Reflecting Harrison's re-engagement with chanting,[84] the song originated from the bhajan he and his companions sang for five hours during their tour of the city's temples.[85][nb 6]

His musical association with Wood led them to co-write "Far East Man",[87] a rumination on friendship,[88] which the pair first recorded for Wood's debut solo album, I've Got My Own Album to Do.[89] Re-recorded by Harrison for Dark Horse, the song was his first foray into 1970s soul music.[90][91] "Māya Love" also reflected Harrison's move towards contemporary R&B, particularly funk.[92] Informed by his relationship with Boyd, the lyrics ponder the illusory nature of love within the Hindu concept of maya.[93][94][nb 7] Like "Māya Love", "Hari's on Tour (Express)" was a showcase for Harrison's slide guitar playing.[97] A rare instrumental in the artist's post-Beatles catalogue, its title referenced the upcoming tour[98] and Hari Georgeson, one of several pseudonyms Harrison used on other artists' recordings.[99]

Given Harrison's comment that the album resembled a TV soap opera, musicologist Thomas MacFarlane likens Dark Horse to a "drama in two acts". The first act opens with the "Hari's on Tour" instrumental, he writes, before giving way to a run of intriguing "mood pieces" in "Simply Shady", "So Sad" and a reinterpretation of the Everly Brothers' "Bye Bye, Love".[100] Harrison rewrote the latter song to address Boyd's eloping with Clapton.[101] The new lyrics include the lines "There goes our lady, with a-you-know-who / I hope she's happy, old Clapper too",[102] and Harrison's claim that he "threw them both out".[103][104] "I Don't Care Anymore", a non-album B-side from this period, is a lighthearted song in which Harrison expresses lust for a married woman.[105][106] The composition blends jug band, skiffle and country influences.[106]

Recording history

[edit]November 1973 – early 1974

[edit]Harrison began work on Dark Horse in November 1973,[107][108] midway through the extended sessions for The Place I Love.[78][109] Recording took place at his 16-track home studio, FPSHOT, in Henley-on-Thames.[110] As on Living in the Material World, Harrison produced the album himself and Phil McDonald again served as recording engineer.[107]

The other musicians playing on the sessions were Starr, Klaus Voormann, Jim Keltner and Gary Wright.[108] They taped the basic tracks for "Ding Dong, Ding Dong", which Harrison envisioned as a Christmas/New Year hit song,[107] and an early version of "Dark Horse".[111][112] Authors Chip Madinger and Mark Easter write that because the line-up on "So Sad" includes pianist Nicky Hopkins, along with Starr and Keltner, the basic track possibly originates from the Material World sessions.[110] Harrison had since given "So Sad" to his near-neighbour Alvin Lee to record for the latter's album On the Road to Freedom.[113] Harrison played on the session, which took place in August, as did Wood.[114]

Harrison did minimal recording of his own over the first half of 1974.[115] Keen to ensure the best musicianship for Splinter's debut, he worked tirelessly on The Place I Love and had Wright, Voormann, Lee and Keltner contribute to some of the recordings.[116] When trying to place the Dark Horse projects with a distributor, he sent the basic tracks for "Ding Dong" and "Dark Horse", along with rough mixes of some Splinter and Shankar songs, to Asylum Records boss David Geffen in Los Angeles, telling Geffen he would see him in March.[72][nb 8] Harrison, Lee and Wood all subsequently added lead-guitar parts to "Ding Dong", as Harrison sought to build up the layers of instrumentation on the song and re-create his former collaborator Phil Spector's signature Wall of Sound.[120] "So Sad" also received a considerable amount of overdubbing,[110] creating what Leng terms a "harrowing encounter" as Harrison expresses his "great despair" at the end of his relationship with Boyd.[121]

April 1974 with the L.A. Express

[edit]I went on a bit of a bender to make up for all the years I'd been married ... I wasn't ready to join AA or anything ... but I could put back a bottle of brandy occasionally, plus all the other naughty things that fly around. I just went on a binge until it got to the point where I had no voice and no body at times.[122]

– George Harrison, February 1979

Leng finds an uncharacteristic spontaneity in Harrison's work ethic on Dark Horse, as his home and recording base were one and the same.[123] In Leng's view, the discipline of working to a schedule "flew out the ornate windows", as did the artist's usual painstaking approach to his music.[5] After attending Joni Mitchell's concert at the New Victoria Theatre in London on 20 April 1974,[124] Harrison was much impressed with her jazz-rock backing band, the L.A. Express, led by saxophonist and flautist Tom Scott,[125] and invited them to Friar Park the following day.[126] Although it was only intended to be a social visit, Harrison and the five musicians recorded the basic tracks for "Hari's on Tour (Express)", which became the opening number on the album and the Harrison–Shankar tour, and "Simply Shady".[107][nb 9] According to Leng, "Hari's on Tour" shows Harrison wanting to be "one of the boys", as a guitarist in a working band, and far from the spiritual songwriter of Material World.[98]

The L.A. Express continued their tour with Mitchell the next day.[126][127] Having formed a rapport with Harrison after they had worked together on Shankar Family & Friends in 1973,[126] Scott subsequently returned to Friar Park and overdubbed horn parts onto "Ding Dong" and the two new tracks. Scott later told journalist Michael Gross that he was the first Western musician that Harrison approached to join him on the upcoming tour.[128]

May–August 1974 extracurricular activities

[edit]Between May and August, Harrison signed the distribution agreement between Dark Horse Records and A&M in Paris and opened offices for the label in Los Angeles, London[129] and Amsterdam.[130] Although Little Malcolm was tied up in the litigation surrounding Apple, the film was eligible for entry in film festivals;[17] that summer, it won a Silver Bear award at the Berlin Film Festival, in June, and went on to win a gold medal at the Atlanta Film Festival.[131][132][nb 10] Through their regular phone calls to discuss the new record label, Harrison formed a bond with Olivia Trinidad Arias,[136][137] who worked in the marketing department at A&M in Los Angeles.[138] Harrison later credited Arias, whom he subsequently married, with saving him from the downward emotional spiral represented in Dark Horse songs such as "Simply Shady".[139][nb 11]

In August, Harrison holidayed in Spain with Kathy Simmons before abruptly ending their relationship to fly to Los Angeles and make arrangements for the tour.[142] He returned to England at the end of the month for publicity work with Splinter.[143] One of the members of Splinter marvelled at Harrison's ability to work for "24 hours straight" in the studio[144] but they were also concerned about how gaunt-looking he had become.[21]

August–October 1974 at Friar Park

[edit]Further sessions for the album took place in August and September.[107] Harrison recorded with four American musicians who formed part of his tour band:[145][146] Billy Preston, his former Apple artist, on keyboards; Scott, who served as band leader on the tour; and the rhythm section of Andy Newmark and Willie Weeks,[7] both of whom Harrison had met while working on Ron Wood's album in July.[72] Newmark recalled that he and Weeks were "completely thrilled" to be invited to play on Dark Horse.[147] He said that Harrison was an easygoing leader who trusted his musicians' instincts and allowed them the freedom to "do our thing".[127]

Harrison taped "Far East Man", "Māya Love" and "His Name Is Legs (Ladies and Gentlemen)" with this group.[148] A tribute to comedian "Legs" Larry Smith,[149] the latter track was left unfinished until the following year, when Harrison completed it for inclusion on Extra Texture (Read All About It).[150] Preston, Weeks and Newmark also played on "It Is 'He' (Jai Sri Krishna)",[151] and Preston and Weeks contributed to some of the songs on The Place I Love.[152][nb 12] Around this time, Shankar arrived in London with his Music Festival from India orchestra;[155][156] for three weeks, they rehearsed and recorded at Friar Park.[41] Harrison produced their eponymous studio album, which Dark Horse released in 1976.[13][118] According to Arias, he continued to work on Dark Horse at night and would wake up to the sound of the orchestra rehearsing in the morning.[157]

On 23 September, Harrison introduced Shankar on stage at London's Royal Albert Hall for the Music Festival's debut performance,[158] before accompanying them on a short tour of Europe.[118] At this point, Harrison still had much of his album to complete, and rehearsals for the North American tour were due to begin in Los Angeles in October.[104][50] Before leaving for the US, Harrison recorded an interview with BBC Radio 1 DJ Alan Freeman in which he performed "Dark Horse", a snippet of "Far East Man", and "I Don't Care Anymore" on acoustic guitar.[159][160] The interview was broadcast on 6 December in the UK but delayed until September 1975 in the US, where it was used to promote Extra Texture.[159]

According to the master tape information, Harrison recorded "Bye Bye, Love" at FPSHOT in October;[100] Scott said he did this alone one night after all the other musicians had left.[128] In addition to engineering the recording,[161] Harrison added a variety of instruments to his acoustic guitar track, including Moog synthesizer, drums, electric pianos and several electric-guitar parts.[71][nb 13]

October 1974 in Los Angeles

[edit]

Rehearsals for the tour began on 15 October.[164][nb 14] Using A&M Studios in Hollywood as his base, Harrison rehearsed with the tour band on a sound stage at the studio complex.[166] Along with Scott, Preston, Weeks and Newmark, the band included L.A. Express guitarist Robben Ford, Harrison's Concert for Bangladesh horn players Jim Horn and Chuck Findley, and jazz percussionist Emil Richards.[26][167] Keltner also participated, on drums,[168] but he would not join the tour until late in November.[155][169] Aside from the Harrison material, selections by Preston and Scott were rehearsed for their spots in the show,[170] since, as at the Bangladesh benefits in 1971, Harrison was keen for other artists to have their moment centre-stage.[128][171] In a fusion of musical cultures,[172] Harrison, Scott and Richards rehearsed with Shankar's orchestra for some of the Indian-music pieces,[173] and all the musicians, Western and Indian, came together for the Shankar Family & Friends tracks "I Am Missing You"[155] and "Dispute & Violence".[170][174]

Harrison was already experiencing a throat condition before arriving in Los Angeles;[5] in Arias's description, his voice became more hoarse as the year wore on.[175] Since industry convention dictated that an artist have new commercial product to promote when touring the US,[5] he was obligated to complete Dark Horse.[176] Outside of the daytime rehearsals, Harrison finished off the songs recorded in England, and mixed the album.[177] Horn and Findley overdubbed flutes, and Richards wobble board onto "It Is 'He'".[82][112] Madinger and Easter suggest that much of the vocals on Dark Horse were taped at this point[118] – a situation that resulted in Harrison overworking and then blowing his voice in the middle of the tour rehearsals.[13][178] He was diagnosed with laryngitis.[5][6] Harrison recorded "I Don't Care Anymore" solo on acoustic guitar, introducing it as an intended B-side.[106]

Although he had intended to finish the version of "Dark Horse" taped at Friar Park, Harrison decided to re-record the song with the tour band, live on the sound stage at A&M Studios.[72][62] The session took place on either 30 or 31 October,[179] with Norm Kinney as engineer.[180] Leng writes of this performance of "Dark Horse": "Anyone wondering what Harrison's voice sounded like on the Dark Horse Tour need look no further: this track was cut only days before the first date in Vancouver. Although the band sounded good, his voice was in shreds ..."[181] MacFarlane says that the song's new arrangement incorporates folk and jazz influences, and likens this musical fusion to Joni Mitchell's work.[182]

Harrison later admitted he was "knackered" by the time he arrived in Los Angeles,[183] having taken on too much over the previous year.[6][184] He also recalled that his business manager, Denis O'Brien, had to force him out of the studio, to ensure he caught the plane for the opening show of the tour, on 2 November.[185][186]

Artwork

[edit]Cover

[edit]The LP's gatefold cover design was credited to Tom Wilkes and includes photography by Terry Doran,[187] a long-time friend of the Beatles and Harrison's original estate manager at Friar Park.[188][189] In a 1987 interview, Harrison said the concept and initial design for the front cover was his own work.[190] The cover image partly recalls that of the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album,[104][191] and reflected Harrison's admiration for Terry Gilliam's animation in Monty Python's Flying Circus.[192]

The cover shows a 1956 Liverpool Institute high-school photograph[193] superimposed on a watercolour painting, which Wilkes created in response to Harrison's request for an Indian effect.[194] The photo sits inside a lotus flower and is surrounded by a dream-like Himalayan landscape that extends to the horizon.[195] At the top of the image, the Indian yogi Mahavatar Babaji floats in the sky,[195] representing Krishna.[196][197] As the founding yogi of the Hindu Nath tradition, Babaji introduced Kriya Yoga, which is said to destroy bad karma brought about by past deeds.[195][nb 15] In the Liverpool Institute photo, a thirteen-year-old Harrison is pictured in the centre of the top row, his face tinted blue; school teachers appear dressed in long-sleeve tops bearing superimposed record-company logos or other symbols.[195] Harrison said he gave the unapproving headmaster the bull's-eye Capitol logo[190] whereas the art teacher, who Harrison liked, received the Om symbol.[200][201] Wilkes and Harrison disagreed over the inclusion of the Babaji image, which the designer disliked and reduced in size for the LP's initial pressing.[195]

The artwork also reflects Harrison's connection with nature, anticipating his later self-identification as a gardener rather than a musician.[202] The inner gatefold spread contains a tinted photo of Harrison and comedian Peter Sellers walking beside a lake[195] at Friar Park.[201] Around the edges of the photo, text asks the "Wanderer through this Garden's ways" to "Be kindly" and refrain from casting "Revengeful stones" if "perchance an Imperfection thou hast found"; the verse concludes: "The Gardener toiled to make his Garden fair, Most for thy Pleasure."[195] A speech balloon emanating from Sellers reads, "Well, Leo! What say we promenade through the park?"[195] This line was taken from the 1968 Mel Brooks film The Producers, a favourite of Sellers and Harrison.[203]

On the back cover, Harrison is pictured sitting on a garden bench, the back timbers of which appear to be carved with his name and the album title.[195] Similar to Harrison's attire in the outdoor scenes of the "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" video clip, Leng refers to his appearance as resembling the Jethro Tull character "Aqualung".[204] Doran's photo, given the same orange hue as the one inside the gatefold,[195] was also used on some European picture sleeves for the "Ding Dong" and "Dark Horse" singles around this time.[205][206] Along the bottom of the cover image sits an Om symbol and Harrison's usual "All glories to Sri Krishna" dedication.[195]

Inner sleeve and labels

[edit]Dark Horse's inner sleeve notes were handwritten by Harrison on a plane at the start of the tour.[128][207] Along with the first Harrison-album credit for FPSHOT,[110] his purple pen records various in-jokes while listing the many contributing musicians.[195] He included Boyd and Clapton's names next to "Bye Bye, Love",[208] leading to the incorrect assumption that they had contributed to the track.[103][209] That song's title is juxtaposed with the words "Hello Los Angeles",[210] while "OHLIVERE" was a reference to Arias.[26][211] The latter is also included among the title track's musician credits – her contribution being "Trinidad Blissed Out".[212] Under "Ding Dong", Harrison credited Wood's guest appearance to "Ron Would If You Let Him", while Sir Frank Crisp is listed as having provided "Spirit".[210]

Arias's face, in a photo taken by tour photographer Henry Grossman, appeared on the record's side-two face label. A corresponding picture of Harrison appeared on side one.[213] Combined with the sequencing of "Bye Bye, Love" on side one and "Ding Dong" as the opening track on side two, this juxtaposition gave the impression that Harrison's was farewelling Boyd and ushering in Arias.[214]

1974 North American tour

[edit]George says people expect him to be exactly what he was ten years ago. He's matured so much in so many ways. That's the problem with all the artists, I suppose ... People like to hear the old nostalgia.[215]

– Ravi Shankar, November 1974

"Dark Horse" was issued as the album's lead single in the US[216] on 18 November.[217] Harrison played the title track, "Hari's on Tour" and "Māya Love" throughout the tour, but due to his delay in completing the album, the new material combined with new arrangements of his better-known songs to produce a setlist that lacked the familiarity expected of a former Beatle.[218] The tour alienated some of rock music's most influential critics,[53][219][220] notably Ben Fong-Torres of Rolling Stone magazine.[21][221] Titled "Lumbering in the Material World",[222] Fong-Torres' article covered the Vancouver and US West Coast stops, ending on 12 November,[223] and was followed by Larry Sloman's reviews of some of the East Coast shows.[224][225] These articles and Rolling Stone's subsequent album review established what became the "given" view, according to Leng, that the Harrison–Shankar tour was a failure.[226] The majority of critics – or those "without axes to grind", author Robert Rodriguez writes[227] – reviewed the concerts favourably.[228][nb 16]

The negative press Harrison received stemmed from his decision to feature Indian music so heavily in the concert programme,[155][233] the tortured quality of his singing voice,[18] and especially his refusal to pander to the Beatles' legacy.[234][235][236] The Beatles were represented in the setlist in four songs.[237] In addition to reworking the arrangements, however, Harrison altered some of the lyrics to reference his deity[205][238] or his failed marriage in the case of "Something", Harrison's most popular Beatles track.[235][239] In his pre-tour press conference, Harrison had dismayed some commentators by stating that he would be happy to be in a band with Lennon but not McCartney, and that he preferred Weeks as a bass player to McCartney.[240][241] When invited to visit US president Gerald Ford in Washington on 13 December, Harrison told journalists that he enjoyed playing with his tour band more than he had being a member of the Beatles.[242]

Release

[edit]Dark Horse was released on 9 December 1974 in the United States (as Apple SMAS 3418),[243] two-thirds of the way through the tour.[110][244] In Britain, where the lead single was "Ding Dong, Ding Dong",[216] the album's release took place on 20 December (with the Apple catalogue number PAS 10008).[243][245] The UK release coincided with the final show of the tour, at Madison Square Garden in New York.[246] It came the day after Harrison and McCartney signed legal papers known as the "Beatles Agreement",[247] to finally dissolve the Beatles partnership, at the Plaza Hotel.[248][249][nb 17]

In the US, Dark Horse received a gold disc from the RIAA on 16 December,[247] and peaked at number 4 on the Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart, although it dropped out of the top 200 after a chart run of seventeen weeks.[107][255] The album also reached number 4 on the national charts compiled by Cash Box and Record World.[107] In Canada, it peaked at number 42 on the RPM Top 100 in early February 1975.[256]

The title track performed well as a single in the US,[72] climbing to number 15 on the Billboard Hot 100.[257] Issued as a follow-up on 23 December, "Ding Dong" peaked at number 36,[258] which was also an achievement since the late release date meant the song was excluded from prearranged holiday-season programming.[72] In the UK, "Ding Dong" stalled at number 38, making it the first Harrison single to miss the top ten there.[259]

Dark Horse peaked inside the top ten in Austria, the Netherlands and Norway,[260] but failed to place on the UK Albums Chart,[261] then a top 50 list.[262] This was a poor result for a former Beatle,[263] further to Starr's Beaucoups of Blues not charting there in 1970.[264] It was an especially dramatic turnaround in Harrison's commercial fortunes,[265] after his three previous solo releases (including the Concert for Bangladesh live album) had all made number 1 or 2 in the UK.[266] Issued as a UK single on 28 February 1975,[267] "Dark Horse" also failed to chart.[268]

Reissue

[edit]Dark Horse was released on CD in January 1992.[269] The album was remastered again and reissued in September 2014, as part of the Harrison box set The Apple Years 1968–75.[270] As bonus tracks, the reissue includes a previously unreleased demo of "Dark Horse"[271] and the long-unavailable "I Don't Care Anymore".[272] Author Kevin Howlett supplied a liner note essay in the CD booklet,[273] while the DVD exclusive to the box set contains Harrison's promotional video for "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" and Capitol's 1974 television ad for the album.[272]

Critical reception

[edit]Contemporary reviews

[edit]Dark Horse received some of the most negative reviews of any release by a Beatle up to that point[274] and the worst of Harrison's career.[275] Released amid the furore surrounding his refusal to play "Beatle George"[276] during a tour that was a "whirlwind of pent-up Beatlemania", in Leng's words, it was as if Harrison had already committed "acts of heresy".[277] Rather than having his new work judged on its own merits, it was "open season" on Harrison;[278] another biographer, Elliot Huntley, has written of the "tsunami of bile" unleashed on the ex-Beatle in late 1974.[279]

In his review subtitled "Transcendental Mediocrity",[280] Jim Miller of Rolling Stone called Dark Horse a "disastrous album" to match the "disastrous tour", and a "shoddy piece of work".[281] In contrast with the praise that the same publication had lavished on Harrison for Living in the Material World the year before,[282] Miller described Dark Horse as a "chronicle of a performer out of his element, working to a deadline, enfeebling his overtaxed talents by a rush to deliver new 'LP product'", and stated: "In plain point of fact, George Harrison has never been a great artist ... the question becomes whether he will ever again become a competent entertainer."[197][281] The NME's Bob Woffinden derided Harrison's songwriting, production and vocals, particularly on two tracks dealing with his troubled personal life, "Simply Shady" and "So Sad". Woffinden concluded: "I find Dark Horse the product of a complete egoist – no one, you see, is in my tree – someone whose universe is confined to himself. And his guru ... I'll repeat that this album is totally colourless. Just stuff and nonsense."[283]

Writing in The Village Voice, Robert Christgau bemoaned the album's "transubstantiations" and particularly ridiculed the lyrics to "Māya Love", "in which 'window-pane' becomes 'window brain.' Can this mean that pain (pane, get it?) is the same as brain? For all this hoarse dork knows ..."[284] Mike Jahn provided a withering assessment in High Fidelity, saying that the US Food and Drug Administration should arrest Harrison for "selling a sleeping pill without a prescription, for a downer this definitely is".[285] Jahn added that only "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" registered with him after three listens, but only due to his incredulity at the lyrics.[286]

By contrast, Billboard's reviewer described the album as "an excellent one" and compared it favourably with Harrison's acclaimed 1970 triple LP, All Things Must Pass.[287] Brian Harrigan of Melody Maker credited Harrison with establishing "a new category in music – Country and Eastern" and lauded his "nifty" slide-guitar playing and "tremendous" singing. Although he found some of the tracks overlong, Harrigan concluded: "Yep, the Sacred Cowboy has produced a good one."[288][289] Combined with his feature on the tour in Circus Raves, in which he questioned the accuracy of the negative reports about the Harrison–Shankar concerts and defended Harrison's desire to move on from the Beatles, Michael Gross described Dark Horse as matching All Things Must Pass in quality, and "surpassing" it at times, thanks to the new album's "clarity of production and lovely songs".[nb 18] He highlighted "So Sad" as a "luxurious track" and described "Ding Dong, Ding Dong", "Dark Horse" and "Far East Man" as "all, simply, good songs".[128][nb 19]

Taken as a metaphor for the album itself, the plea for tolerance inside the LP sleeve[191] – "Be kindly Wanderer through this Garden's ways ..." – was ridiculed at the time by some critics.[104][291] In the 1978 edition of their book The Beatles: An Illustrated Record, Roy Carr and Tony Tyler termed these lines of verse "a self-pitying slab of sub-Desiderata".[292] Carr and Tyler conceded that the playing on Dark Horse was "impeccable", but opined that Harrison's lyrics were "sanctimonious, repetitive, vituperative and self-satisfied"; as for the album as a whole: "One wishes it had not come from an ex-Beatle."[292] Writing in his 1977 book The Beatles Forever, Nicholas Schaffner found some justification in reviewers' sniping at the "shoddy performance" and "preachy, humorless message" on Dark Horse.[235] Schaffner singled out "Bye Bye, Love" and "Ding Dong" for derision, but praised the title track and Harrison's guitar work on "Hari's on Tour (Express)" and especially "So Sad".[293] Schaffner said that neither the album nor the tour deserved the level of abuse it received in some sections of the press.[294] "It was George's turn anyway", Schaffner reflected, "to be inflicted with the poison-pen treatment that the critics had earlier accorded Paul and John. Knocking idols off their pedestals makes for excellent copy."[294][nb 20]

Retrospective assessments

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | C−[296] |

| Mojo | |

| MusicHound Rock | 3.5/5[298] |

| Music Story | |

| OndaRock | 6/10[300] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Uncut | |

Writing for Rolling Stone shortly after Harrison's death in November 2001, Greg Kot approved of Dark Horse's "jazzier backdrops" compared with Material World, but opined that his voice turned much of the album into an "unintentionally comic exercise".[302] In the same publication, Mikal Gilmore identified Dark Horse as "one of Harrison's most fascinating works – a record about change and loss".[274][nb 21] Writing in the 2004 edition of The Rolling Stone Album Guide, Mac Randall said that, in persevering with Dark Horse despite his laryngitis, Harrison "ruins several decent songs with croaky vocals".[304][305]

Richard Ginell of AllMusic highlights "Dark Horse" and the "exquisite" "Far East Man" but rues that, in issuing an album when his voice was ravaged by laryngitis, Harrison eroded much of the prestige he had gained over his former bandmates as a solo artist.[191] Mojo's John Harris describes Dark Horse as "Not pretty ... a tanking long-player", with "Far East Man" the only redeeming track.[297] Paul Du Noyer, writing for Blender, also highlights the Harrison–Wood collaboration, while deeming the album "ragged, unhappy" and indicative of Harrison's "uncharacteristic spell of rock-star excess".[295]

Among reviews of the 2014 Apple Years reissue, Richard Williams wrote in Uncut that Dark Horse is an album that "only a devoted Apple scruff could love",[306] while Scott Elingburg of PopMatters opined: "What makes Dark Horse so unique is that, aside from All Things Must Pass, Dark Horse sounds and feels like Harrison is playing music like he has nothing to lose and all the world to gain."[307] Writing for PopMatters in 2012, Pete Prown said that, as with Lennon and McCartney solo releases, the album displayed a lack of focus but it remained the target of unfair critical scorn. In Prown's view, the same quality that incensed critics originally – "its sloppy, jammy sound, which would have been heresy in the over-produced '70s" – had since been validated in a pop culture informed by post-punk and grunge, and had lent the album a redemptive "garage/DIY grit".[308]

In his review of the Apple Years box set, for Classic Rock magazine, Paul Trynka writes that "The surprise of this set ... is the albums whose quietness and introspection were out of tune with the mid-70s. Dark Horse ... [is] packed with beautiful, small-scale moments." While identifying "Simply Shady" and the title track among the standouts, Trynka adds: "Only 'Ding Dong, Ding Dong' embarrasses ..."[309] AllMusic editor Stephen Thomas Erlewine describes Dark Horse as "a mess but ... a fascinating one".[310]

In his book on the Beatles' first ten years as solo artists, Robert Rodriguez rates Dark Horse a "near-great" work, like Lennon's Mind Games and Rock 'n' Roll, adding that Harrison's "hot streak" only ended with Extra Texture.[311] Ultimate Classic Rock ranked Dark Horse 31st (out of 63) in their list of the best Beatles solo albums released up to late 2018.[312] In a similar list, Junkee ranks it at number 5, describing the album as a "big, footstomping masterpiece" that has improved with age, and "a work of considerable beauty, held in place by the crushing, excellent titular song".[313]

Legacy

[edit][With] its rough edges, the naked autobiography, the mean and depressed lyrics were all new twists in a highly produced and perfectionist career. Dark Horse fascinates today because of this harsh, helpless honesty. In contrast to his friend Dylan's poetically elevated Blood on the Tracks, recorded almost simultaneously, it's a break-up album brought low by real life.[86]

– Nick Hasted, Uncut Ultimate Music Guide, 2018

Dave Thompson, in his 2002 article on Harrison's career for Goldmine, wrote that Dark Horse signalled the end of the artist's post-Beatles "magic" and that, rather than being listened to in its own right, the LP had since been remembered for its association with Harrison's record label and the controversial 1974 tour, and for being the first "major Beatle album" to miss the UK chart.[314] Harrison never completely forgave Rolling Stone – which had previously championed his work since 1970[315] – for the treatment he received during this period.[227][316][nb 22] In his biography of Rolling Stone founding editor Jann Wenner, Joe Hagan cites the magazine's treatment as indicative of Wenner's willingness to create enemies. He says that Harrison's disdain for Rolling Stone "put him in good company" in the mid-1970s – namely, Lennon, Mitchell, Bob Dylan and the Eagles.[319]

Simon Leng bemoans the state of Harrison's voice and the "sonic patchwork" nature of the set, but comments that "So Sad" and "Far East Man" were received positively when first released by Alvin Lee and Ron Wood, respectively.[320] In the case of "So Sad", he attributes this to "the difficulty of being George Harrison in 1974", during a year when other artists, including Lennon with Walls and Bridges and Clapton with 461 Ocean Boulevard, were incorporating elements of Harrison's sound in their work and enjoying favourable reviews.[321] The difference in winter 1974–75, Leng continues, was that, by championing Shankar's Indian music segments during the tour and neglecting his duties as an ex-Beatle in America, Harrison had "committed the cardinal counterculture sin – he had rejected 'rock 'n' roll'".[322] Cultural historian Michael Frontani recognises the reception afforded Dark Horse, particularly by Rolling Stone, and the tour as a reflection of Harrison's "growing hostility with the rock press". He finds Jim Miller's review for the magazine "relentlessly negative" and unjustified in its vitriol, given the record's musicianship and its place as Harrison's "most funky and R&B-inflected album" up to that time.[315]

Nick Hasted, writing in the Uncut Ultimate Music Guide issue on Harrison, credits the album with possessing a captivating quality, and he describes the record as a "raw and ragged diary" of the year when Harrison "lost his wife and his solo superstardom". With Harrison maintaining his friendships with Clapton and Starr, Hasted continues, the "incestuous absurdity" behind Dark Horse makes it a "recording studio soap opera" that anticipates Fleetwood Mac's Rumours.[86]

Track listing

[edit]All songs by George Harrison, except where noted.

Side one

- "Hari's on Tour (Express)" – 4:43

- "Simply Shady" – 4:38

- "So Sad" – 5:00

- "Bye Bye, Love" (Felice Bryant, Boudleaux Bryant, Harrison) – 4:08

- "Māya Love" – 4:24

Side two

- "Ding Dong, Ding Dong" – 3:40

- "Dark Horse" – 3:54

- "Far East Man" (Harrison, Ron Wood) – 5:52

- "It Is 'He' (Jai Sri Krishna)" – 4:50

2014 reissue bonus tracks

- "I Don't Care Anymore" – 2:44

- "Dark Horse" (Early Take) – 4:25

Personnel

[edit]According to 1974 LP credits, via Castleman and Prodrazik's book All Together Now (except where noted).[323] Track numbers refer to CD and digital versions of the album.

- George Harrison – vocals (2–9), electric and acoustic guitars (1–9), Moog synthesizer (4, 9), clavinet (3, 4, 6), organ (6),[324] bass (4), percussion (4, 5, 6, 9), gubgubbi (9), drums (4), backing vocals (2–6, 8, 9)

- Tom Scott – saxophones (1, 2, 5, 6, 8), flute (7, 9), horn arrangements (1, 2, 5, 6, 8), organ (1)

- Billy Preston – electric piano (5, 7, 8), organ (9), piano (9)

- Willie Weeks – bass (3, 5, 7–9)

- Andy Newmark – drums (5, 7–9), percussion (8)

- Jim Keltner – drums (3, 6, 7)

- Robben Ford – electric guitar (1, 2), acoustic guitar (7)

- Jim Horn – flute (7, 9)

- Chuck Findley – flute (7, 9)

- Emil Richards – percussion (7, 9)

- Ringo Starr – drums (3, 6)

- Klaus Voormann – bass (6)

- Gary Wright – piano (6)

- Nicky Hopkins – piano (3)

- Roger Kellaway – piano (1, 2), organ (2)

- Max Bennett – bass (1, 2)

- John Guerin – drums (1, 2)

- Ronnie Wood – electric guitar (6)

- Alvin Lee – electric guitar (6)

- Mick Jones – acoustic guitar (6)

- Lon & Derrek Van Eaton – backing vocals (7)

- uncredited – female choir (6)[93]

Chart positions

[edit]| Chart (1974–75) | Position |

|---|---|

| Australian Kent Music Report[325] | 47 |

| Austrian Albums Chart[260] | 10 |

| Canadian RPM Top Albums[256] | 42 |

| Dutch MegaChart Albums[326] | 5 |

| Japanese Oricon LP Chart[327] | 18 |

| New Zealand Albums Chart[328] | 29 |

| Norwegian VG-lista Albums[329] | 7 |

| US Billboard Top LPs & Tape[330] | 4 |

| US Cash Box Top 100 Albums[331] | 4 |

| US Record World Album Chart[332] | 4 |

| West German Media Control Albums[333] | 45 |

Shipments and sales

[edit]

|

|

Notes

[edit]- ^ His friend Klaus Voormann has referred to Harrison taking an obvious "step back" on his spiritual journey.[20] Voormann also expressed concern about Harrison's cocaine use, saying he "became unreliable".[21]

- ^ When discussing the Dark Horse period in a 1979 interview, Harrison likened his life to the BBC radio drama Mrs. Dale's Diary.[35][36]

- ^ Inspired by the flurry of legal activity by Apple and the four former bandmates now being united against Klein,[55] speculation about a possible Beatles reunion dominated the international music press from February through to the end of April.[56] This was accompanied by David Geffen offering them $30 million to reunite for one album, two theatre producers preparing stage adaptations of the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album, and the first of promoter Bill Sargent's multi-million-dollar offers for the Beatles to re-form for a single concert.[57] The widespread nostalgia for the band was also reflected in the successful Beatlefest convention, first held in New York in July 1974.[58]

- ^ Despite dividing music critics, Material World furthered Harrison's standing as the most accomplished former Beatle.[66] According to pop historian Robert Rodriguez, McCartney then usurped Harrison in April 1974, when the singles from his and Wings' 1973 LP Band on the Run belatedly propelled the album and McCartney to a position of commercial and popular dominance.[67]

- ^ He and Boyd saw in the 1973–74 New Year with a party at Starr's Tittenhurst Park home, soon after Harrison had declared his love for Maureen Starkey.[76] In her autobiography, Boyd recalls Harrison telling her at the party: "Let's have a divorce this year."[77]

- ^ Citing a remark Harrison later made to Rolling Stone, music journalist Nick Hasted comments that even in such rare moments of transcendence on the album, "Dark Horse kept confessing ... 'I'm a very poor example of a spiritual person.'"[86]

- ^ Clapton was taken aback at Harrison's reaction to his declaration of love for Boyd.[95] According to Clapton, Harrison viewed such attachments as "all maya" and gave him his blessing while expressing interest in a girlfriend of Clapton's.[96]

- ^ Harrison returned from India in early March.[117] That same month, he carried out further recording on Shankar Family & Friends at A&M Studios in Los Angeles.[118][119]

- ^ Guitarist Robben Ford recalls that on arrival at Friar Park, at around 1 pm, the musicians were entertained by Boyd until Harrison woke up, at which point the couple "didn't interact and she just disappeared". He says the recording session began at 1 am.[127]

- ^ In June 1974, according to Beatles historian Kevin Howlett,[133] Harrison began recording "Can't Stop Thinking About You" for Dark Horse.[134] The track, which includes contributions from Hopkins, Voormann and Keltner,[135] was completed in 1975 for Harrison's final Apple album, Extra Texture (Read All About It).[133]

- ^ In I, Me, Mine, Harrison says that "Simply Shady" is "about what happens to naughty boys in the music business".[140] Arias recalls of the Dark Horse period: "Everything in his life had changed at that point: getting divorced, Apple was in turmoil, he had his own personal demons. '74 was one of those breaking-through-the-sound-barrier periods. You come through and it's just quiet on the other side."[141]

- ^ Harrison's multitracked vocals on "It Is 'He'" lack the raspy quality that characterises Dark Horse,[153] suggesting he recorded the song at an earlier date.[82] The 2014 CD booklet shows the master sheet for his rough mixes of the track, dated 11 June 1974.[154]

- ^ According to Boyd, she visited Friar Park around this time after returning from the US, where she had accompanied Clapton on his 461 Ocean Boulevard tour.[162] She comments that Harrison "looked so sad" and she questioned whether she had made the right choice.[163]

- ^ In his 23 October press conference for the tour, Harrison said he had arrived in Los Angeles "just over a week" before.[165]

- ^ Babaji was one of the four yogis Harrison chose for inclusion on the cover of Sgt. Pepper.[198][199] He wore a Babaji badge on his shirt or jacket during the 1974 tour.[195]

- ^ Scott, Keltner, Weeks, Horn, Newmark and Richards have each identified "the Dark Horse Tour" as a career highpoint.[229][230][231] The fusion of Western and Eastern musical styles in the concerts served as a precursor to the world music genre.[2][7][232]

- ^ Starr chose not to come to New York, to avoid being subpoenaed by Allen Klein[250] as the latter sought to retrieve funds he believed owed to his company ABKCO by his three former clients.[251] With regard to loans made to Harrison, Klein sought control of the US arm of the Harrisongs publishing company.[252][253] Harrison's stopover in New York, including the post-tour party attended by Lennon, was therefore the focus of multiple attempts by Klein-appointed private investigators to serve him with a subpoena.[254]

- ^ Gross concluded the article by saying: "A poet once wrote that 'If a man's reach cannot exceed his grasp, then what's a heaven for?' It's words like those that drive George Harrison now ... not the fading, but still glorious memory of 'I Wanna Hold Your Hand'."[128]

- ^ Sue Byrom of Record Mirror said that, apart from "Hari's on Tour", side one of the LP was overly reliant on All Things Must Pass-era musical and lyrical themes, and that the album only "kicks off properly" with "Ding Dong". She added: "If the first side had contained the variety and progression of the second, it would be a great album ..."[290]

- ^ Recalling the concerts he attended, Schaffner said that fans were drawn to the "exquisite music" being played as the venues filled up – namely, Splinter's The Place I Love. He added: "It sounded like a gorgeous fantasy of what George's album should have sounded like. The opulent production, the jangling guitars, even the silky vocal harmonies, reminded one of the glories of All Things Must Pass far more than did [Dark Horse]."[99]

- ^ Alan Clayson similarly writes of the interest factor of "a non-Beatle, as well as an ex-Beatle in uncertain transition", and while classing the album as "an artistic faux pas", describes "It Is 'He' (Jai Sri Krishna)" as "wonderful" and "startling".[303]

- ^ Scott complained to Circus Raves that Fong-Torres had overly focused on the tour's opening show, even though the reporter was fully aware of the programme changes they introduced after Vancouver.[128] In a 1975 interview, Harrison said he could accept criticism but it had come from "one basic source" and therefore appeared personal. He recalled that one of the journalists had submitted a favourable tour article in which this writer also stated his opposition to the publication's earlier stance, yet all the favourable comments about the music and the audience's response were removed after he submitted the piece.[317] In Harrison's description, Rolling Stone had "just edited everything positive out".[318]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Leng, p. 159.

- ^ a b Nick DeRiso, "Gimme Five: Gary Wright, Robben Ford, Bobby Whitlock, Alan White, Joey Molland on George Harrison" > "'Dark Horse' ...", Something Else!, 25 February 2014 (archived version retrieved 21 June 2021).

- ^ a b Steven Rosen, "George Harrison", Rock's Backpages, 2008 (subscription required).

- ^ George Harrison, p. 69.

- ^ a b c d e f Leng, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Olivia Harrison, p. 312.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez, p. 60.

- ^ Badman, p. 111.

- ^ Woffinden, p. 75.

- ^ Soocher, p. 83.

- ^ Woffinden, p. 74.

- ^ Badman, pp. 94, 98.

- ^ a b c d Lavezzoli, p. 195.

- ^ Clayson, p. 346.

- ^ Badman, p. 150.

- ^ Kahn, pp. 206–07.

- ^ a b Michael Simmons, "Cry for a Shadow", Mojo, November 2011, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d Rodriguez, p. 58.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 274.

- ^ Klaus Voormann interview, in George Harrison: Living in the Material World.

- ^ a b c David Cavanagh, "George Harrison: The Dark Horse", Uncut, August 2008, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Doggett, pp. 208–09.

- ^ Tillery, p. 94.

- ^ Boyd, pp. 178–79.

- ^ Leng, pp. 152, 156, 159.

- ^ a b c Badman, p. 135.

- ^ Tillery, p. 93.

- ^ Harry, p. 394.

- ^ Badman, p. 113.

- ^ a b Schaffner, p. 176.

- ^ Clayson, p. 329.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 423.

- ^ Badman, p. 136.

- ^ Anne Moore, "George Harrison on Tour – Press Conference Q&A", Valley Advocate, 13 November 1974; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required; retrieved 15 July 2012).

- ^ Mick Brown, "A Conversation with George Harrison", Rolling Stone, 19 April 1979 (retrieved 2 August 2016).

- ^ Kahn, p. 279.

- ^ Olivia Harrison, pp. 258, 302.

- ^ Leng, pp. 157, 165.

- ^ Leng, pp. 148, 157, 165.

- ^ Olivia Harrison, p. 302.

- ^ a b Booklet accompanying Ravi Shankar–George Harrison Collaborations box set (Dark Horse Records, 2010; produced by Olivia Harrison), p. 15.

- ^ Clayson, p. 335.

- ^ Huntley, pp. 107, 108.

- ^ Badman, p. 125.

- ^ Schaffner, pp. 176, 188.

- ^ Woffinden, p. 85.

- ^ Badman, p. 131.

- ^ Frontani, p. 159.

- ^ Leng, p. 165.

- ^ a b The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 44, 126.

- ^ Woffinden, pp. 73, 83.

- ^ Leng, pp. 165–66.

- ^ a b The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 44.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 199.

- ^ Doggett, pp. 216–17.

- ^ Badman, pp. 118, 124–25.

- ^ Doggett, pp. 217, 223.

- ^ Schaffner, p. 170.

- ^ Inglis, p. 43.

- ^ Clayson, p. 324.

- ^ Allison, p. 139.

- ^ a b George Harrison, p. 288.

- ^ Alan Freeman (host), "Interview with George Harrison", Rock Around the World, show 61, 5 October 1975.

- ^ Hunt, p. 103.

- ^ Inglis, pp. 23, 46–47.

- ^ Schaffner, pp. 159–60.

- ^ Rodriguez, pp. 159, 263.

- ^ Inglis, p. 45.

- ^ George Harrison, pp. 240, 282.

- ^ Huntley, p. 109.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 152.

- ^ a b c d e f Madinger & Easter, p. 444.

- ^ Boyd, pp. 144, 145.

- ^ Olivia Harrison, p. 268.

- ^ Badman, p. 144.

- ^ O'Dell, p. 266.

- ^ Boyd, p. 177.

- ^ a b Howlett, p. 4.

- ^ Rodriguez, pp. 382–83.

- ^ Allison, pp. 86–87, 154.

- ^ Leng, pp. 150–51, 165.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez, p. 384.

- ^ Clayson, p. 330.

- ^ Allison, p. 147.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 297.

- ^ a b c Nick Hasted, "George Solo: Dark Horse", Uncut Ultimate Music Guide: George Harrison, TI Media (London, 2018), pp. 70–71.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 343, 344.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 235.

- ^ Badman, p. 109.

- ^ Leng, p. 156.

- ^ Rodriguez, pp. 234–35.

- ^ Leng, p. 153.

- ^ a b Inglis, p. 46.

- ^ Allison, p. 150.

- ^ Tillery, p. 106.

- ^ Eric Clapton interview, in George Harrison: Living in the Material World.

- ^ Clayson, p. 336.

- ^ a b Leng, p. 150.

- ^ a b Schaffner, p. 179.

- ^ a b MacFarlane, p. 90.

- ^ Hunt, p. 22.

- ^ a b Nigel Williamson, "All Things Must Pass: George Harrison's post-Beatles solo albums", Uncut, February 2002, p. 60.

- ^ a b Clayson, p. 343.

- ^ a b c d Woffinden, p. 84.

- ^ Allison, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Inglis, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f g Spizer, p. 264.

- ^ a b Kahn, p. 186.

- ^ Leng, pp. 143, 153.

- ^ a b c d e Madinger & Easter, p. 443.

- ^ Leng, pp. 153, 155.

- ^ a b Madinger & Easter, pp. 443–44.

- ^ Badman, p. 110.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 129, 206–07.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 197.

- ^ Leng, pp. 143–45.

- ^ Greene, p. 211.

- ^ a b c d Madinger & Easter, p. 442.

- ^ Doggett, p. 217.

- ^ Leng, pp. 153–54.

- ^ Leng, p. 151.

- ^ Doggett, p. 225.

- ^ Leng, pp. 148, 149.

- ^ "Joni Mitchell on Sat, April 20, 1974 at New Victoria Cinema, London, England". www.setlist.fm. November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Michael G. Nastos, "L.A. Express" Archived 30 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine, AllMusic (retrieved 3 January 2012).

- ^ a b c Leng, p. 149.

- ^ a b c Mat Snow, "George Harrison: Quiet Storm", Mojo, November 2014, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b c d e f g Michael Gross, "George Harrison: How Dark Horse Whipped Up a Winning Tour", Circus Raves, March 1975; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required; retrieved 14 July 2012).

- ^ Badman, pp. 125, 129.

- ^ Clayson, p. 345.

- ^ Harry, p. 249.

- ^ Badman, pp. 128, 129.

- ^ a b Kevin Howlett (liner note essay), Extra Texture (Read All About It) CD booklet (Apple Records, 2014; produced by George Harrison), p. 9.

- ^ "Announcing The Apple Years 1968–75 Box Set – Released 22nd September", georgeharrison.com, 2 September 2014 (retrieved 10 October 2014).

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 195–96.

- ^ Tillery, p. 115.

- ^ Rodriguez, pp. 423–24.

- ^ Huntley, p. 120.

- ^ Kahn, pp. 278–79.

- ^ Allison, p. 154.

- ^ Michael Simmons, "Cry for a Shadow", Mojo, November 2011, p. 84.

- ^ Harry, p. 342.

- ^ Badman, p. 129.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 346, 479.

- ^ MacFarlane, pp. 91, 92.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 443–44, 447.

- ^ Leng, p. 157.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 443–44, 453.

- ^ Spizer, p. 275.

- ^ MacFarlane, pp. 100–01.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 197.

- ^ Leng, p. 143.

- ^ Clayson, p. 344.

- ^ Howlett, pp. 2, 15.

- ^ a b c d Lavezzoli, p. 196.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, p. 447.

- ^ Howlett, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Badman, p. 133.

- ^ a b Badman, p. 138.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, p. 445.

- ^ MacFarlane, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Boyd, pp. 178–79, 184.

- ^ Boyd, p. 184.

- ^ Andrew Bailey (with David Hamilton), "George Harrison: The Niceman Cometh", Rolling Stone, 21 November 1974; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Kahn, pp. 183, 187.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 126.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 442–43, 445, 446.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 322.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, p. 449.

- ^ a b Madinger & Easter, p. 446.

- ^ Leng, pp. 167, 169, 176.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 198.

- ^ Leng, pp. 173–74.

- ^ DVD extra, George Harrison: Living in the Material World.

- ^ Howlett, p. 5.

- ^ Greene, p. 212.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 442–43.

- ^ Tillery, p. 114.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 443, 444.

- ^ Spizer, p. 260.

- ^ Leng, p. 155.

- ^ MacFarlane, p. 92.

- ^ MacFarlane, p. 93.

- ^ Badman, p. 197.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, pp. 443, 445.

- ^ Huntley, pp. 114–15.

- ^ Harry, p. 143.

- ^ Clayson, p. 319.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 71fn.

- ^ a b Timothy White, "George Harrison: Reconsidered", Musician, November 1987, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d Richard S. Ginell, "George Harrison Dark Horse" Archived 13 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine, AllMusic (retrieved 13 June 2021).

- ^ Clayson, p. 271.

- ^ Olivia Harrison, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Harry, p. 391.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Spizer, p. 265.

- ^ Allison, p. 47.

- ^ a b Huntley, p. 113.

- ^ Greene, p. 77.

- ^ Tillery, p. 81.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 23.

- ^ a b Howlett, p. 6.

- ^ Allison, p. 71.

- ^ Clayson, p. 307.

- ^ Leng, p. 154.

- ^ a b Peter Doggett, "George Harrison: The Apple Years 1968–75", Record Collector, April 2001, p. 39.

- ^ "George Harrison – Ding Dong, Ding Dong", dutchcharts.nl (retrieved 3 January 2013).

- ^ Mark Ellen, "A Big Hand for The Quiet One", Q, January 1988, p. 66.

- ^ Lindsay Planer, "George Harrison 'Bye Bye, Love'" Archived 12 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, AllMusic (retrieved 22 March 2012).

- ^ Rodriguez, pp. 65, 72.

- ^ a b Spizer, p. 267.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 357, 363.

- ^ Lindsay Planer, "George Harrison 'Dark Horse'" Archived 22 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, AllMusic (retrieved 20 June 2012).

- ^ Spizer, pp. 265, 268.

- ^ Woffinden, pp. 84–85.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 128.

- ^ a b Spizer, p. 259.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 143.

- ^ Huntley, p. 116.

- ^ Kahn, p. 183.

- ^ Frontani, pp. 160–61.

- ^ Greene, p. 214.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 46.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 125–26.

- ^ Leng, pp. 160, 164–65.

- ^ Hagan, p. 303.

- ^ Leng, p. 174.

- ^ a b Rodriguez, p. 59.

- ^ Leng, pp. 160–65, 174.

- ^ Lavezzoli, pp. 204–05.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 238.

- ^ Leng, pp. 168, 170, 173–74.

- ^ Leng, pp. 168, 173, 177.

- ^ Clayson, p. 339.

- ^ Leng, p. 166.

- ^ a b c Schaffner, p. 178.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 126, 128.

- ^ Leng, pp. 168–69.

- ^ MacFarlane, p. 94.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 336, 338–39.

- ^ Doggett, pp. 224–25.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 409.

- ^ Soocher, p. 173.

- ^ a b Castleman & Podrazik, p. 144.

- ^ Spizer, p. 263.

- ^ Badman, p. 145.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, p. 451.

- ^ a b Badman, p. 139.

- ^ Doggett, p. 227.

- ^ Rodriguez, pp. 201, 410–12.

- ^ Huntley, p. 118.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 412.

- ^ Soocher, pp. 82, 110.

- ^ Doggett, pp. 211, 213–15.

- ^ Soocher, pp. 173, 174–76.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 332, 365.

- ^ a b "RPM Top Albums, 1 February 1975" Archived 18 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Library and Archives Canada (retrieved 5 March 2012).

- ^ Schaffner, p. 195.

- ^ Badman, pp. 146, 151.

- ^ Harry, pp. 154–55.

- ^ a b "George Harrison – Dark Horse" Archived 27 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, austriancharts.at (retrieved 7 May 2013).

- ^ Harry, p. 142.

- ^ "The History of the Official Charts: the Seventies", Official Charts Company (retrieved 12 March 2022).

- ^ Clayson, p. 348.

- ^ Spizer, p. 288.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 201.

- ^ Spizer, p. 239.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 149.

- ^ Huntley, pp. 121–22.

- ^ Madinger & Easter, p. 635.

- ^ Joe Marchese, "Review: The George Harrison Remasters – 'The Apple Years 1968–1975'" Archived 4 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Second Disc, 23 September 2014 (retrieved 26 September 2014).

- ^ Brennan Carley, "George Harrison's 'Dark Horse' Demo Is a Homespun Delight" Archived 5 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Spin, 16 September 2014 (retrieved 26 September 2014).

- ^ a b Joe Marchese, "Give Me Love: George Harrison's 'Apple Years' Are Collected on New Box Set" Archived 3 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Second Disc, 2 September 2014 (retrieved 3 September 2014).

- ^ "George Harrison: 'The Apple Years 1968–75' Box Set Due September 23" Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Guitar World, 4 September 2014 (retrieved 1 October 2014).

- ^ a b The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 46.

- ^ Greene, p. 213.

- ^ Greene, pp. 214–15.

- ^ Leng, pp. 166, 195.

- ^ Leng, p. 177.

- ^ Huntley, p. 114.

- ^ Frontani, p. 267.

- ^ a b Jim Miller, "Dark Horse: Transcendental Mediocrity", Rolling Stone, 13 February 1975, p. 76 (archived version retrieved 31 January 2014).

- ^ Huntley, pp. 112, 114.

- ^ Bob Woffinden, "Platters: George Harrison Dark Horse", NME, 21 December 1974, p. 18; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required; retrieved 15 July 2012).

- ^ Robert Christgau, "Consumer Guide (52)" Archived 3 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, robertchristgau.com (retrieved 31 January 2014).

- ^ Frontani, pp. 160, 267.

- ^ Mike Jahn, "The Lighter Side: George Harrison, Dark Horse", High Fidelity, April 1975, p. 101.

- ^ Bob Kirsch (ed.), "Top Album Picks" Archived 18 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Billboard, 21 December 1974, p. 63 (retrieved 27 May 2015).

- ^ Brian Harrigan, "Harrison: Eastern Promise", Melody Maker, 21 December 1974, p. 36.

- ^ Hunt, p. 95.

- ^ Sue Byrom, "George Harrison: Dark Horse", Record Mirror, 21 December 1974, p. 11.

- ^ Leng, p. 181.

- ^ a b Carr & Tyler, p. 113.

- ^ Schaffner, pp. 178–79.

- ^ a b Schaffner, p. 177.

- ^ a b Paul Du Noyer, "Back Catalogue: George Harrison", Blender, April 2004, pp. 152–53.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "George Harrison: Dark Horse". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the '70s. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306804093. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ a b John Harris, "Beware of Darkness", Mojo, November 2011, p. 82.

- ^ Graff & Durchholz, p. 529.

- ^ "George Harrison" > "Discographie de George Harrison" (in French), Music Story (archived version from 5 October 2015, retrieved 29 December 2016).

- ^ Gabriele Gambardella, "George Harrison: Il Mantra del Rock", OndaRock (retrieved 24 September 2021).

- ^ Brackett & Hoard, p. 367.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 188.

- ^ Clayson, pp. 344–45.

- ^ Brackett & Hoard, pp. 367–68.

- ^ "George Harrison: Album Guide", rollingstone.com (archived version retrieved 5 August 2014).

- ^ Richard Williams, "George Harrison The Apple Years 1968–75", Uncut, November 2014, p. 93.

- ^ Scott Elingburg, "George Harrison: The Apple Years 1968–1975", PopMatters, 30 January 2015 (archived version retrieved 1 February 2021).

- ^ Pete Prown, "The Worst of George Harrison: How a Pop Icon Made Some of the Most Disappointing Albums Ever", PopMatters, 5 August 2012 (archived version retrieved 13 June 2021).

- ^ Paul Trynka, "George Harrison: The Apple Years 1968–75" Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Classic Rock, November 2014 (retrieved 29 November 2014).

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine, "George Harrison The Apple Years" Archived 13 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, AllMusic (retrieved 1 November 2014).

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 183.

- ^ Michael Gallucci, "Paul McCartney: 'Egypt Station' Review" > "Ranking the Other Beatles Solo Albums", Ultimate Classic Rock, 5 September 2018 (archived version retrieved 3 February 2021).

- ^ Joseph Earp, "Every Beatles Solo Record Ranked from Absolutely Terrible to Life-Changing" Archived 14 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Junkee, 19 August 2019 (retrieved 3 February 2021).

- ^ Dave Thompson, "The Music of George Harrison: An album-by-album guide", Goldmine, 25 January 2002, p. 17.

- ^ a b Frontani, p. 160.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone, pp. 108, 111, 139.

- ^ Kahn, pp. 209–10.

- ^ Clayson, p. 338.

- ^ Hagan, pp. 301–03.

- ^ Leng, pp. 148, 151, 156.

- ^ Leng, pp. 151, 159.

- ^ Leng, p. 175.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 194–98.

- ^ "George's original [inner] sleeve design for the album Dark Horse" (sample album credits), Dark Horse CD booklet (Apple Records, 2014; produced by George Harrison), p. 8.

- ^ David Kent, Australian Chart Book 1970–1992, Australian Chart Book (St Ives, NSW, 1993; ISBN 0-646-11917-6).

- ^ "George Harrison – Dark Horse" Archived 11 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, dutchcharts.nl (retrieved 7 May 2013).

- ^ "a-ザ・ビートルズ – Yamachan Land (Archives of the Japanese record charts): Albums Chart Daijiten – The Beatles" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. 30 December 2007 (retrieved 22 September 2009).

- ^ "George Harrison – Dark Horse" Archived 15 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, RIANZ/charts.org.nz (retrieved 2 October 2009).

- ^ "George Harrison – Dark Horse" Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, norwegiancharts.com (retrieved 7 May 2013).

- ^ "Dark Horse > Charts & Awards > Billboard Albums" Archived 27 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, AllMusic (retrieved 2 October 2009).

- ^ "Cash Box Top 100 Albums", Cash Box, 1 February 1975, p. 49.

- ^ "The Album Chart", Record World, 1 February 1975, p. 42.

- ^ "Album – George Harrison, Dark Horse" Archived 17 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, charts.de (retrieved 3 January 2013).

- ^ "RIAA Gold & Platinum − Searchable Database". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Recording Industry Association of America (retrieved 3 October 2009).

- ^ "George Harrison: Chart Action (Japan)" Archived 7 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, homepage1.nifty.com, October 2006 (retrieved 3 October 2009).

Sources

[edit]- Dale C. Allison Jr, The Love There That's Sleeping: The Art and Spirituality of George Harrison, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8264-1917-0).

- Keith Badman, The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001, Omnibus Press (London, 2001; ISBN 0-7119-8307-0).

- Pattie Boyd (with Penny Junor), Wonderful Today: The Autobiography, Headline Review (London, 2007; ISBN 978-0-7553-1646-5).

- Nathan Brackett & Christian Hoard (eds), The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th edn), Fireside/Simon & Schuster (New York, NY, 2004; ISBN 0-7432-0169-8).

- Roy Carr & Tony Tyler, The Beatles: An Illustrated Record, Trewin Copplestone Publishing (London, 1978; ISBN 0-450-04170-0).

- Harry Castleman & Walter J. Podrazik, All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975, Ballantine Books (New York, NY, 1976; ISBN 0-345-25680-8).

- Alan Clayson, George Harrison, Sanctuary (London, 2003; ISBN 1-86074-489-3).

- Peter Doggett, You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup, It Books (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8).

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, Harrison, Rolling Stone Press/Simon & Schuster (New York, NY, 2002; ISBN 0-7432-3581-9).

- Michael Frontani, "The Solo Years", in Kenneth Womack (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles, Cambridge University Press (Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-139-82806-2), pp. 153–82 & 265–74.

- George Harrison: Living in the Material World DVD, 2 discs (Roadshow Entertainment/Grove Street Productions, 2011; directed by Martin Scorsese; produced by Olivia Harrison, Nigel Sinclair & Martin Scorsese).

- Gary Graff & Daniel Durchholz (eds), MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide, Visible Ink Press (Farmington Hills, MI, 1999; ISBN 1-57859-061-2).

- Joshua M. Greene, Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison, John Wiley & Sons (Hoboken, NJ, 2006; ISBN 978-0-470-12780-3).

- Joe Hagan, Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine, Knopf (New York, NY, 2017; ISBN 978-0-345-81505-7).

- George Harrison, I Me Mine, Chronicle Books (San Francisco, CA, 2002 [1980]; ISBN 0-8118-3793-9).

- Olivia Harrison, George Harrison: Living in the Material World, Abrams (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4197-0220-4).

- Bill Harry, The George Harrison Encyclopedia, Virgin Books (London, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7535-0822-0).

- Kevin Howlett, liner notes, Dark Horse CD booklet (Apple Records, 2014; produced by George Harrison).

- Chris Hunt (ed.), NME Originals: Beatles – The Solo Years 1970–1980, IPC Ignite! (London, 2005).

- Elliot J. Huntley, Mystical One: George Harrison – After the Break-up of the Beatles, Guernica Editions (Toronto, ON, 2006; ISBN 1-55071-197-0).

- Ian Inglis, The Words and Music of George Harrison, Praeger (Santa Barbara, CA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-313-37532-3).

- Ashley Kahn (ed.), George Harrison on George Harrison: Interviews and Encounters, Chicago Review Press (Chicago, IL, 2020; ISBN 978-1-64160-051-4).

- Peter Lavezzoli, The Dawn of Indian Music in the West, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 0-8264-2819-3).

- Simon Leng, While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison, Hal Leonard (Milwaukee, WI, 2006; ISBN 1-4234-0609-5).

- Thomas MacFarlane, The Music of George Harrison, Routledge (Abingdon, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-138-59910-9).

- Chip Madinger & Mark Easter, Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium, 44.1 Productions (Chesterfield, MO, 2000; ISBN 0-615-11724-4).

- Chris O'Dell (with Katherine Ketcham), Miss O'Dell: My Hard Days and Long Nights with the Beatles, the Stones, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and the Women They Loved, Touchstone (New York, NY, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4).

- Robert Rodriguez, Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980, Backbeat Books (Milwaukee, WI, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4).

- Nicholas Schaffner, The Beatles Forever, McGraw-Hill (New York, NY, 1978; ISBN 0-07-055087-5).

- Stan Soocher, Baby You're a Rich Man: Suing the Beatles for Fun and Profit, University Press of New England (Lebanon, NH, 2015; ISBN 978-1-61168-380-6).

- Bruce Spizer, The Beatles Solo on Apple Records, 498 Productions (New Orleans, LA, 2005; ISBN 0-9662649-5-9).

- Gary Tillery, Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George Harrison, Quest Books (Wheaton, IL, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8356-0900-5).

- Bob Woffinden, The Beatles Apart, Proteus (London, 1981; ISBN 0-906071-89-5).

Further reading

[edit]- Eoghan Lyng, "George Harrison's 'Dark Horse' at 45", CultureSonar, 21 November 2019.

- Tony Thompson, "51 Disappointing Albums: 'Dark Horse' by George Harrison", Daily Review, 11 May 2020.

External links

[edit]- Dark Horse at Discogs (list of releases)