Pioneer Zephyr

| Pioneer Zephyr Burlington Zephyr The Silver Streak (unofficial) | |

|---|---|

A postcard advertising the newly introduced Burlington Zephyr, later officially renamed Pioneer Zephyr | |

The coach seating area of Pioneer Zephyr as it appears on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago | |

| Stock type | diesel-electric passenger one-directional trainset |

| In service | 1934–1960 |

| Manufacturer | Budd Company |

| Constructed | 1934 |

| Entered service | November 11, 1934 |

| Number built | 1 trainset (3 cars) |

| Formation | 1: cab/engine/storage 2: baggage/RPO/buffet/coach 3: coach/observation[1] |

| Fleet numbers | 9900 |

| Capacity | 72 passenger seats, 25 long tons (25 t; 28 short tons) of baggage[2] |

| Operators | Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad |

| Specifications | |

| Car body construction | stainless steel |

| Train length | 197 ft 2 in (60.10 m)[1] |

| Car length | 74 ft 0.125 in (23 m) (power car) 57 ft 8 in (17.58 m) (intermediate car) 63 ft 6 in (19.35 m) (rear car)[3] |

| Width | 9 ft 1.0625 in (277 cm) (body) 9 ft 10 in (300 cm) (handrails)[3] |

| Height | 12 ft 1.1875 in (369 cm)[1] |

| Wheel diameter | 36 in (910 mm) (drive wheels), 30 in (760 mm) (ride wheels)[4] |

| Weight | 208,061 lb (94,375 kg)[1] |

| Prime mover(s) | EMD 201A |

| Engine type | diesel |

| Cylinder count | 8 |

| Cylinder size | 8 in (200 mm) bore, 10 in (250 mm) stroke[4] |

| Traction motors | 2 |

| Power output | 660 hp (490 kW)[4] |

| AAR wheel arrangement | B-(2+2)-2 |

| Wheels driven | 2 |

| Bogies | 1 motor bogie,

2 non-motor Jacobs bogies, 1 non-motor bogie |

| Seating | open coach (2+2), observation lounge |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

The Pioneer Zephyr is a diesel-powered trainset built by the Budd Company in 1934 for the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad (CB&Q), commonly known as the Burlington Route. The trainset was the second internal combustion-powered streamliner built for mainline service in the United States (after the Union Pacific Railroad's M-10000), the first such train powered by a diesel engine, and the first to enter revenue service.

The trainset consists of one power/storage car, one baggage/RPO/buffet/coach car, and one coach/observation car. The cars are made of stainless steel, permanently articulated together with Jacobs bogies. The construction incorporated recent advances such as shotwelding (a specialized type of spot welding) to join the stainless steel, and unibody construction and articulation to reduce weight. It was the first of nine similarly built trainsets made for Burlington and its technologies were pivotal in the subsequent dieselization of passenger rail service.

Its operating economy, speed, and public appeal demonstrated the potential for diesel-electric-powered trains to revitalize and restore profitability to passenger rail service that had suffered a catastrophic loss of business with the Great Depression. Originally named the Burlington Zephyr during its demonstration period, it became the Pioneer Zephyr as Burlington expanded its fleet of Zephyr trainsets.

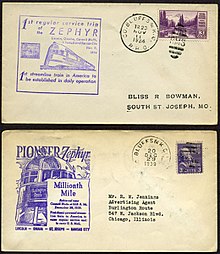

On May 26, 1934, it set a speed record for travel between Denver and Chicago when it made a 1,015.4-mile (1,633 km) non-stop "Dawn-to-Dusk" dash in 13 hours 5 minutes at an average speed of almost 78 mph (124 km/h).[5] For one section of the run it reached a speed of 112.5 mph (181 km/h). The historic dash inspired a 1934 film ("The Silver Streak") and the train's nickname, "The Silver Streak".[6][7][8][9]

The train entered regular revenue service on November 11, 1934, between Kansas City, Missouri; Omaha, Nebraska; and Lincoln, Nebraska. It operated this and other routes until its retirement in 1960, when it was donated to Chicago's Museum of Science & Industry, where it remains on public display. The train is generally regarded as the first successful streamliner on American railroads.[9][10]

Concept and construction

[edit]

In the early 1930s, the Great Depression caused a catastrophic loss of business for American railroads. Passenger service had been losing ridership to automobile travel since the mid-1920s,[11] making faster, more efficient service imperative for railroads to compete. Railroads needed to lower operating costs of passenger service and boost ridership with a more modern image for the traveling public, to restore profitability to passenger service.[12]

One of the railroad presidents who faced this challenge was Ralph Budd, formerly of the Great Northern Railway and from 1932 president of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad (the Burlington Route).[13] In 1932 Ralph Budd met Edward G. Budd (no relation), an automotive steel pioneer who was founder and president of the Budd Company. Edward Budd was demonstrating his new Budd-Michelin rubber-tired rail cars built of stainless steel.[13] Pneumatic-wheeled railcars never found popularity for actual service in the US — they tended to derail — but they demonstrated the successful construction of lightweight stainless steel unibody railcars. Some power-trailer car sets in that series articulated with Jacobs bogies shared between cars embodied the basic elements of car construction that would be used to build a lightweight streamliner train.[14]

Stainless steel provided many benefits over traditional wood and hardened steel for railroad carbodies; it was a lighter and stronger material, and its natural silver appearance and resistance to corrosion meant that it would not have to be painted to protect it from the weather. Since the carbody was much lighter than similar cars, it would be able to carry a higher revenue load for the same cost.[12][14]

In developing the Budd-Michelin railcars, the Budd Company used the formed steel technology in which they were industry pioneers and solved the most difficult problem in using stainless steel for railcar construction: developing a welding technique that would not compromise the strength and corrosion resistance of the stainless steel. On August 20, 1932, Earl J. Ragsdale, an engineer at the Budd Company, filed a patent application for a "Method and product of electric welding"; on January 16, 1934, the United States Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) granted US patent 1,944,106 to the Budd Company.[15] Shotwelding, as Ragsdale termed his method,[16] involved automatic control of the timing of individual spot welds. In spot welding, the two pieces of metal that are to be joined are pressed together with an electrode on each side of the joint. A very high electric current is passed through the joint and fuses the two pieces of metal together.[17] If a spot weld is heated too long, heat will spread from the weld at a middling temperature that weakens the stainless steel and compromises its corrosion-resistant properties unacceptably; Ragsdale's precisely-timed welds solved the problem.[14][18]

The articulated design of some Budd-Michelin cars, with trucks shared between adjacent cars, presented another opportunity for weight saving with the new train.[19] On conventional passenger cars, each carbody rode upon a pair of trucks (pivot-mounted wheel-axle assembly), with one truck at each end. The articulation not only reduced the number of trucks under the train, but it also dispensed with the need for couplers between each of the carbodies, further reducing the train's weight. The concept was used by Budd engineer Walter B. Dean to build a train consisting of three semi-permanently attached cars.[20] However, this also meant that individual cars could not be removed from or added to the trainset easily, either to adjust to demand or to make repairs to an individual car without sidelining the entire train.[21]

Budd was familiar with the development of stationary diesel engines, and believed their superior reliability and fuel economy could be an asset for train transport as well. He brought his idea to the Winton Engine Company (a General Motors subsidiary), and together they designed and produced a new 660 horsepower (490 kW) engine small enough to fit inside a train, solving the question of propulsion.[22]

The exterior design of the train was left to aeronautical engineer Albert Gardner Dean (Walter Dean's younger brother) who designed the sloping nose shape, with architects Paul Philippe Cret and John Harbeson, devising a way to strengthen and beautify the sides with the train's horizontal fluting.[23][24] On April 15, 1936, Colonel Ragsdale, Walter Dean and Albert Dean, filed patent applications for a "Rail Car Front End Construction". On September 23, 1941 the USPTO granted US patents 2,256,493[25] and 2,256,494[26] to the Budd Company. The streamlining extended to the undercarriage as well to reduce drag.[14]

Budd took the task of naming the train very seriously. He wanted a name that started with the letter Z because this train was intended to be the "last word" in passenger service; Budd and his coworkers looked up the last words in their dictionaries, but neither zymurgy nor zyzzle conveyed the meanings that Budd was looking for. While the word "zephyr" had seen previous use[A 1], Budd found his inspiration in The Canterbury Tales, which he had been reading. The story begins with pilgrims setting out on a journey, inspired by the budding springtime and by Zephyrus, the gentle and nurturing west wind. Budd thought that would be an excellent name for a sleek new traveling machine—Zephyr.[12][28][29]

The first Zephyr (9900) was completed by the Budd Company on April 9, 1934.[7][10]

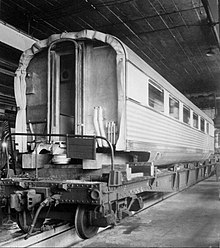

The first car, which measured 71 feet 5 inches (21.77 m), contained the cab, engine compartment and a mail storage area. The train's engineer sat in a small compartment in the nose of the train, directly in front of the prime mover. The main generator was mounted to the prime mover and sat between the engineer's and fireman's seats in the front of the power car. Behind the engine in the power car was a 19-foot long (5.8 m) storage-mail compartment. The second car, measuring 57 feet 8 inches (17.6 m) long, was a combination 30 ft (9.1 m) long express, checked baggage and railway post office section, followed by a short buffet and 20-passenger coach section. The third and final car in the train, measuring 63 feet 6 inches (19.35 m) long as originally built, was configured as half coach (40-passenger seats) and half observation car (12 passenger seats). As built, the train had 72 seats and could carry 50,000 pounds (22.7 tonnes) of baggage and express freight.[30] After a series of demonstration runs, the trainset was named the Burlington Zephyr on April 18, 1934, at the Pennsylvania Railroad's Broad Street Station in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[31][32][33] As the first of several Zephyr trainsets built for Burlington, the original trainset was renamed the Pioneer Zephyr once additional named trainsets entered service.[23]

- Interiors of Pioneer Zephyr

-

Cab with controls in the power car

-

The engine in the power car

-

The RPO section in the power car

-

Seats in open coach

-

Observation lounge in the rear car

Promotion: "Dawn-to-Dusk" dash

[edit]

After its naming in Philadelphia, the train was taken on a three-week promotional tour of cities in the Northeast and Midwest. The train was open for viewing in several cities, with 24,000 people viewing it in Philadelphia,[32] 50,000 in Rochester, New York,[34] and more than 109,000 viewing it in New York City.[32] In early May 1934, the train was driven back westward over the Pennsylvania Railroad's mainline to Chicago, and some parallel routes, exceeding 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) several times.[32] At its stop in Dayton, Ohio, another 20,000 people viewed the train,[35] and a "never-ending procession of visitors" viewed it on its stop in Indianapolis.[36] It was then driven toward Denver for its last display in preparation for its next big promotion. It made additional promotional stops in other cities along the route, including Lincoln, Nebraska, where 21,000 people viewed the train.[37] The tour stopped in 46 cities and had almost 485,000 people view the train at its many stops.[32]

The train made a "Dawn-to-Dusk" dash from Denver to Chicago on May 26, 1934, in a publicity stunt timed to coincide with the opening day of the second year of the Century of Progress world's fair in Chicago. The railroad spared no expense in planning the operations. All other trains along the Zephyr's route were diverted to sidings and the turnouts were spiked into the proper alignment for the Zephyr's run.[38] Track and maintenance of way workers checked every spike and bolt along the train's route to ensure that there would not be any problems, and temporary speed signs were installed along the route to warn the Zephyr's crew of curves that would be dangerous at high speeds.[6] On the day of the dash, every road grade crossing was staffed by a flagger to stop automobile traffic ahead of the train and to ensure that the crossing was clear.[39] Stations along the route were protected by local police officers and members of the American Legion and the Boy Scouts of America.[40]

The train left Denver at 07:04 Central Daylight Time and at 20:09, 13 hours 5 minutes later, broke through the tape at the designated finish line at Halsted Street station, 1.8 miles west of Chicago Union Station. The train's average speed from start to finish was 77 mph (124 km/h); and had reached a speed of 112.5 mph (181 km/h). The non-stop 1,015 mile (1,633 km) trip exceeded the railroad's expectations in being 1 hour 55 minutes faster than was scheduled.[6] The Burlington's contemporary passenger trains plied the same distance in around 25 hours.

Riding the train were Ralph Budd, Edward G. Budd, Harold L. Hamilton, president of the Electro-Motive Corporation, a number of reporters, some Burlington employees, members of the public,[41] and Zeph, a burro that was contributed by a Colorado newspaper, the Rocky Mountain News, as a mascot for the train.[6] The newspaper had described Zeph to the railroad as a "Rocky Mountain canary" so the train's crew had originally planned only enough space for a birdcage; when they found out it was not a bird, the railroad hastily built a pen in the baggage section and bought some hay for it. When asked about the burro, Ralph Budd replied "why not? One more jackass on this trip won't make a difference."[42][43]

The train continued east from Halsted Station to the 1934 Century of Progress fair on the Lake Michigan shore, where it arrived for the "Wings of a Century" pageant on opening day.[6] After its showing on the Wings of a Century stage, and one day on public display at the Fair,[44] the train was taken on a 31-state, 222-city publicity tour. More than two million people saw the train before it entered revenue service.[45] Part of this tour included a test run between Chicago and Minneapolis - Saint Paul,[46] completing the test trip in just over six hours,[47] besting the Burlington Route's fastest steam-powered service by five hours and convincing the railroad to promptly place orders with Budd and GM for two more Zephyr trainsets.[19]

Revenue service and additional Zephyr trains

[edit]Even before the Burlington Route's new trainsets could be built, east coast railroads Boston and Maine Railroad and Maine Central Railroad ordered a nearly identical copy of the Pioneer Zephyr from Budd and GM, which began service between Boston and Bangor, Maine, in February 1935 as the Flying Yankee.[48] Budd and GM delivered the first additional Zephyrs, identical trainsets 9901 and 9902, in time for an April 1935 debut as the Twin Zephyrs, operating between Chicago and Minneapolis - Saint Paul.[19] In all, the Burlington Route ordered eight additional Zephyrs, gradually departing from the semi-permanently coupled design of the Pioneer Zephyr towards regularly coupled cars that could easily be interchanged.[49]

The Winton two-stroke diesel engines used in the Zephyr power units and early EMC designs, while a breakthrough in locomotive power, were an immature technology. Some of their early reliability problems were mitigated with changes to individual parts such as pistons; other solutions had to wait for a differently designed engine. For example, the first generation of pistons in the Winton engine only had about 50,000 miles of useful life, later extended to about 100,000 miles. GM's next generation diesel engine had pistons with a useful life of over 500,000 miles. The problems were most acute under the operating conditions of locomotive, rather than stationary or marine, use.[50] Even with the problems of the Winton 201A, their maintenance regime was significantly lower than for steam locomotives.

The Zephyr's power (leading) car was numbered 9900, the baggage-coach combine car 505, and the coach-observation 570. The train was placed in regular service between Kansas City, Missouri, Omaha and Lincoln, Nebraska, on November 11, 1934, with the train numbered 21 northbound and 20 southbound. The trainset replaced a pair of steam locomotives and six heavyweight passenger cars, weighing up to eight times as much as the Zephyr.[45] By June 1935, it proved popular enough to add a fourth car, providing additional coach seating.[4] The fourth car was originally a 40-seat coach number 525, but the following June it was switched to Twin Cities service, then back to the Pioneer Zephyr in December.[19] Car 525 remained on the train until June 1938. Just over five years after it was introduced, the Pioneer Zephyr crossed the one million mile mark in regular service on December 29, 1939, near Council Bluffs, Iowa.

On the second anniversary of the train's famous dash, the original Burlington Zephyr was renamed the Pioneer Zephyr to distinguish it as the first of the Burlington's growing Zephyr fleet. In 1938, car 525 was replaced by car number 500, a 40-seat buffet/lounge car, to provide light meals. Car number 505, the baggage-coach combine, was rebuilt at this time into a full baggage car, but it kept its original windows.[7][51]

In 1939 the Pioneer Zephyr was involved in a head-on collision with a freight train that completely destroyed the cab. Five mail clerks were injured and the engineer was killed, and the accident drove home the advantages for crew safety of the elevated, behind-the-nose cab design of the contemporary EMC E-series locomotives. The train was rebuilt and re-entered revenue service soon afterward.[52][8]

Ralph Budd and the Burlington capitalized on the Zephyr's success. Many of the Burlington's named passenger trains began operating under the Zephyr brand. After the nine original Zephyr sets were completed during 1934–1939, standard production model diesel passenger locomotives with improved engines became available. Trains consisting of the new locomotives with new streamlined cars of standard size were ordered. Burlington ordered its new EMC E5 passenger diesels with matching stainless-steel fluting and operated their new full-size, long-distance trains under the Zephyr brand, with perhaps the best known being the California Zephyr.

In 1948 and 1949, the Pioneer Zephyr was temporarily removed from service to participate in the Chicago Railroad Fair's "Wheels A-Rolling" pageant. The fair's purpose was to celebrate 100 years of railroad history west of Chicago, and the Pioneer Zephyr's role in the pageant was to highlight the latest strides in railroad technology. It resumed regular passenger operations when the fair ended on October 2, 1949.[53] The fourth car that was added in 1935 was removed in May 1950.[54] By 1955 the Pioneer Zephyr's route had been updated to run between Galesburg, Illinois, and Saint Joseph, Missouri; the trainset had been in continual service since 1934, operating over nearly 3 million miles (4.8 million kilometres). The Pioneer Zephyr's last revenue run was a trip from Lincoln, Nebraska, to Kansas City, Missouri, (along the train's regular revenue route) that then continued to Chicago on March 20, 1960.[7]

The California Zephyr made its last runs as a full service between California and Chicago in 1970 following the Western Pacific Railroad's withdrawal, with the Rio Grande and Burlington Route successor Burlington Northern Railroad designating successor trains for their portions of the route under the names Rio Grande Zephyr and California Zephyr Service respectively. Government-formed Amtrak took over most passenger rail services in 1971, and finally succeeded in reviving the full California Zephyr in 1983.[55]

Zephyr as cultural phenomenon

[edit]"Silver Streak" film

[edit]

Press publicity had apparently first coined the term "Silver Streak". The Pioneer Zephyr's famous Denver-Chicago dash served as the inspiration for the 1934 film The Silver Streak starring Charles Starrett.[23][45] In that story, the crew was racing to the Boulder Dam construction site with an iron lung, with only moments to spare. The original Zephyr trainset was used for the exterior shots in the film, while interior scenes were filmed on a soundstage in Hollywood. For the film, the "Burlington Route" nameplate on the train's nose was replaced with one that read "Silver Streak".

Zephyr tributes in advertising, commercial products, and sports

[edit]With Zephyr-mania sweeping the country, tributes turned up in the names of everything from sports teams to commercial products. In 1934, Father Becker, principal of the St. Mary Catholic High School in Menasha, Wisconsin, was so inspired by the dawn-to-dusk run that he chose "Zephyrs" as the mascot for the school. In Galesburg, Illinois, which is 162 rail miles from Chicago, the local high school named all its athletic teams the "Galesburg Silver Streaks" in honor of the train. In 1935, the H. N. White Company changed the name of its top-line saxophones to "King Zephyr." Ford introduced the Lincoln-Zephyr with the 1936 model year. Northwest Airlines' promotional materials from the late 1930s referred to their fleet of airliners as "Sky Zephyrs."[56] If advertisers could find a way to cash in on Zephyr-mania, they did.

Legacy

[edit]Influence on future trains

[edit]While a revolutionary design, the Pioneer Zephyr was not the first streamliner—that title went to the M-10000 of the Union Pacific Railroad, which made its first trip in February 1934.[57] However, the Pioneer Zephyr had several key differences, including the use of a diesel powerplant and stainless steel construction, in contrast to the M-10000's gasoline powerplant and aluminum construction. These two design decisions had a profound influence on future streamliners and other passenger trains, which had more in common with the Zephyr than the M-10000.[58] The streamlined Hiawathas launched by the Milwaukee Road in 1935 were a direct response to (and directly competed with) the Burlington Route's Zephyrs.[59]

Later years

[edit]On May 26, 1960, the 26th anniversary of the "Dawn-to-Dusk" dash, the original Pioneer Zephyr train (car numbers 9900, 505 and 570) was donated to Chicago's Museum of Science & Industry (MSI).[7][23] Car number 500, which operated with the train from 1938, went along with Mark Twain Zephyr trainset 9903 to a party in Mount Pleasant, Iowa, for static display in a town park, but plans for the train's display did not work out; in 2002 car 500 and the Mark Twain Zephyr were stored in Granite City, Illinois, with plans to display it in Fairfield, Iowa.[60] As of 2020, there are plans to restore the trainset to operational condition.[61]

MSI displayed the Pioneer Zephyr outdoors, with no protection from the weather, until 1994. At that time, the steam locomotive that shared the display space with the Zephyr, Santa Fe #2903, was donated to the Illinois Railway Museum (IRM) at Union, west of Chicago, while MSI prepared a new display location for the Zephyr.[62]

MSI dug a pit in front of the building and built a new display area for the Zephyr, where it could be displayed year-round. In 1998, after the train received a cosmetic restoration by Northern Rail Car in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the pit was finally ready to receive the train. The Pioneer Zephyr train is now on display at MSI just outside the main entrance from the museum's underground parking area, where it is one of the more popular exhibits.[62] In November 2019, MSI temporarily closed the exhibit to add new interactive elements and an expanded experience.[63] The exhibit re-opened to the public in March 2021.[64]

Other Zephyr trains

[edit]In addition to the Pioneer Zephyr, several other legacies remain. An operable Nebraska Zephyr train was donated to IRM. There, powered by one of the large "E" series passenger diesels (an EMC E5) with the distinctive and durable stainless-steel fluting, it is still operated on short runs on the museum's substantial trackage, providing train enthusiasts and tourists with an experience reminiscent of the heyday of the Burlington's Zephyr service.[65][66] The Silver Charger, power car of the General Pershing Zephyr, is on display at the National Museum of Transportation in St Louis, and the same train's "diner-parlour and observation car" is now the Silver Star Cafe in Port Hedland, Australia.[citation needed] The Flying Yankee trainset is preserved at the Hobo Railroad in New Hampshire.[48]

Also utilizing the name, the Minnesota Zephyr was a dinner train located in the historic city of Stillwater, Minnesota, although it was not directly associated with the historic Burlington Zephyr fleet.[67][68]

Dorney Park & Wildwater Kingdom in Allentown, Pennsylvania, has a miniature replica train ride called Zephyr which was built in 1935 and helped the park survive the Great Depression.[69]

Models

[edit]Due to the Zephyr's place in American railroad history, many model railroaders have built their own versions of the Pioneer Zephyr in miniature. Several model manufacturers are now producing commercial ready-to-run models or kits of the train for modelers to build. This list is ordered by the manufacturer's release date:

- American Flyer introduced one of the earliest versions of the Zephyr in 1934. Originally sold as a three-car set, the body shells were produced in sand-cast aluminum and hand-polished to represent the stainless steel-skinned prototype. Additional cars became available and the locomotive or "power unit" underwent some refinements during production; and a less expensive stamped lithographed steel version was also produced. The Zephyr set appeared in the 1934-1938 American Flyer catalogs. With the purchase of the American Flyer line in 1937 by the AC Gilbert Company, a new line of O scale (1:48) trains moved into production phasing out the Zephyrs and previous O-scale products collectively known as "Chicago Flyer".[70]

- Challenger Imports imported limited production ready-to-run brass models in HO scale (1:87) of the four-car Pioneer Zephyr, Mark Twain Zephyr and the Boston and Maine Railroad's Maine Cheshire and Maine Minuteman in 1993.[71]

- Fine N-Scale Products released a kit in 1996 in N scale (1:160) that includes an option for car number 500.[72]

- Con-Cor made limited-run models available in both HO scale and N scale that were released in 2005, and then again in 2012.[73]

- River Raisin Models released a ready-to-run model in S scale (1:64) of both the Pioneer Zephyr (in three- and four-car configurations) and the similar Flying Yankee, in 2005.[74]

- MTH Electric Trains released a limited production ready-to-run model of the three-car Pioneer Zephyr in O scale in 2005.[75]

See also

[edit]- "Fliegender Hamburger" ("Flying Hamburger")—a German diesel trainset that entered service in 1933, regularly achieving speeds of up to 100 mph (160 km/h).

- ETR 200—Italian high-speed electric train.

- High-speed rail

Notes

[edit]- ^ for instance, Shakespeare used the word in his 1611 play Cymbeline.[27]

- ^ a b c d Byron 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Byron 2005, pp. 23, 29.

- ^ a b Wegman 2008, p. 46, 47.

- ^ a b c d Byron 2005, p. 26.

- ^ Schafer, Mike; Welsh, Joe (1997). Classic American Streamliners. Osceola, Wisconsin: MBI Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 0-7603-0377-0. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021..

- ^ a b c d e "Pioneer Zephyr - A Legendary History". excerpts from the New York Times. Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. May 27, 1934. Archived from the original on February 8, 2005. Retrieved February 24, 2005.

- ^ a b c d e Gordon-Gilmore, Randy (2002). "Pioneer Zephyr". ProtoTrains. Archived from the original on March 7, 2005. Retrieved February 24, 2005.

- ^ a b Johnston, Welsh & Schafer 2001, p. 15.

- ^ a b Zimmermann 2004, p. 16.

- ^ a b Zimmermann 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Byron 2005, p. 6.

- ^ a b c "American Experience / Streamliners / People & Events / Ralph Budd". PBS Online / WGBH. 2000. Archived from the original on March 9, 2005. Retrieved February 22, 2005.

- ^ a b Byron 2005, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d "The Burlington Zephyr stainless steel train". Advanced Materials & Processes. American Society for Materials. June 2009. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ US patent 1944106, Earl J. W. Ragsdale, "Method and product of electric welding", issued 1934-01-15, assigned to Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Company

- ^ Byron 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Zimmermann 2004, p. 19.

- ^ "Pioneer without Profit". Fortune. February 1937. p. 130.

- ^ a b c d Johnston, Welsh & Schafer 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Zimmermann 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Schafer & Welsh 2002, p. 19.

- ^ Schafer & Welsh 2002, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Johnston, Welsh & Schafer 2001, p. 16.

- ^ Zimmermann 2004, p. 24.

- ^ US patent 2256493, Earl J. W. Ragsdale & Albert G. and Walter P. Dean, "Rail car front end construction", issued 1941-09-23, assigned to Budd Manufacturing Company

- ^ US patent 2256494, Earl J. W. Ragsdale & Albert G. Dean, "Rail car front end construction", issued 1941-09-23, assigned to Budd Manufacturing Company

- ^ "Definition of ZEPHYR".

- ^ Kisor 1994, p. 16.

- ^ Zimmermann 2004, p. 29.

- ^ All specs from Byron 2005, p. 23

- ^ Zimmermann 2004, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e Byron 2005, p. 39.

- ^ "The Burlington Zephyr: First Look, April 1934". Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2019 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Howden, Norman (April 30, 1934). "50,000 Jam Station to See Newest Marvel of the Rails". Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Crowd of Nearly 20,000 on Hand at Union Station To See New Burlington "Zephyr" Streamline Train". The Dayton Herald. Dayton, Ohio. May 7, 1934. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Burlington's Zephyr, Latest in Trains, Draws Many Visitors on Stay Here". The Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. May 10, 1934. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Burlington "Zephyr" Here for Exhibition". The Hastings Democrat. Hastings, Nebraska. May 24, 1934. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Byron 2005, p. 53.

- ^ Byron 2005, p. 52.

- ^ Zimmermann 2004, p. 37.

- ^ Byron 2005, p. 36.

- ^ "Pioneer Zephyr, a legendary history - The Dawn To Dusk Club". Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. 2002. Archived from the original on February 9, 2005. Retrieved March 1, 2005.

- ^ Byron 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Byron 2005, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Zimmermann 2004, p. 40.

- ^ Byron 2005, pp. 48–49.

- ^ "Train scoots 71 miles hour". Star Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota. July 31, 1934. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Johnston, Welsh & Schafer 2001, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Schafer & Welsh 2002, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Kettering, E.W. (November 29, 1951). History and Development of the 567 Series General Motors Locomotive Engine. ASME 1951 Annual Meeting. Atlantic City, New Jersey: Electro-Motive Division, General Motors Corporation. Archived from the original on May 8, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ Zimmermann 2004, p. 43.

- ^ Green Bay Press-Gazette; Wed, Oct 4, 1939; Page 9

- ^ Chicago Railroad Fair Official Guide Book. 1949.

- ^ Byron 2005, p. 62.

- ^ Schafer & Welsh 2002, pp. 69–70.

- ^ "Northwest Airlines timetable, 1939". timetableimages.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- ^ Johnston, Welsh & Schafer 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Johnston, Welsh & Schafer 2001, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Johnston, Welsh & Schafer 2001, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Lotz, David (Spring 2002). "History of the Mark Twain Zephyr". Rail Merchants International. Archived from the original on March 6, 2005. Retrieved February 27, 2005.

- ^ "'Mark Twain Zephyr' to run again". Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "The Pioneer Zephyr comes home". Trackside. Archived from the original on February 22, 2005. Retrieved February 25, 2005.

- ^ "All Aboard the Pioneer Zephyr - Museum of Science and Industry". November 19, 2019. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ "Museum Of Science And Industry Reopens Pioneer Zephyr Train After Sweeping Renovations To Historic "Silver Streak"". Museum of Science & Industry. Archived from the original on July 18, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ "History of the IRM: Collections". Illinois Railway Museum. November 25, 2005. Archived from the original on April 29, 1998. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- ^ "History of the IRM: Restoration". Illinois Railway Museum. November 25, 2005. Archived from the original on April 29, 1998. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- ^ Dougherty, Mike (December 30, 2001). "Zephyr relives days of stylish travel". St. Cloud Times. Saint Cloud, MN. p. 22 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Molene, John (May 9, 2003). "Zephyr is more than just a train". St. Cloud Times. Saint Cloud, MN. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dorney Park & Wildwater Kingdom (2006). "Rides: Zephyr". Cedar Fair Entertainment Company. Archived from the original on June 18, 2006. Retrieved June 15, 2006.

- ^ American Flyer Trains consumer catalogs 1934 - 1938

- ^ "Shovelnoses". BPL Brassworks. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ^ "Burlington Zephyr". Fine N-Scale Products. 2002. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ^ ""HO" and "N" Scale Con-Cor 1934 Pioneer Zephyr". Con-Cor. 2007. Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ^ "Budd "Shovelnose" Trainsets Delivered!". River Raisin Models. 2007. Archived from the original on May 15, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ^ "Pioneer Zephyr Diesel Passenger Set w/Proto-Soundr 2.0". MTH Electric Trains. Archived from the original on July 9, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

References

[edit]- American Society of Mechanical Engineers (November 18, 1980). "The Pioneer Zephyr" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2005.

- Byron, Carl R. (2005). The Pioneer Zephyr: America's First Diesel-Electric Stainless Steel Streamliner. Forest Park, IL: Heimberger House Publishing Company. ISBN 0-911581-58-8.

- Johnston, Bob; Welsh, Joe; Schafer, Mike (2001). The Art of the Streamliner. New York: Metro Books. ISBN 978-1-58663-146-8.

- Kisor, Henry (1994). Zephyr: Tracking a Dream Across America. Holbrook, Massachusetts: Adams Publishing Group. ISBN 1-55850-477-X.

- Schafer, Mike; Welsh, Joe (2002). Streamliners: history of a railroad icon. Motorbooks classics (1. publ ed.). St. Paul, Min: Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-1371-8.

- "Trains Timeline". Trains. February 2005. p. 9.

- Wayner, Robert J., ed. (1972). Car Names, Numbers and Consists. New York: Wayner Publications. OCLC 8848690.

- Zimmermann, Karl (2004). Burlington's Zephyrs. Saint Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-1856-0.

- Wegman, Mark (2008). American Passenger Trains and Locomotives Illustrated. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press. pp. 44–52. ISBN 978-0-7603-3475-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Morgan, David P. (1963). Diesels West. Evolution of power on the Burlington. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. LCCN 62019987. OCLC 2671997.

- Chronicle of the rise of diesel power on the Burlington with specific emphasis on the Pioneer Zephyr, its record-setting run, and its descendants.

- "The Burlington Zephyr". Rail Enthusiast. EMAP National Publications. January 1983. pp. 10–13. ISSN 0262-561X. OCLC 49957965.

- Reisdorff, James J.; Bartels, Michael M. (2021). The Pioneer Zephyr: Silver Streak Across Nebraska. David City, Nebraska: South Platte Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-7340266-6-5.

External links

[edit]- All Aboard the Silver Streak: Pioneer Zephyr, image and exhibit of the Pioneer Zephyr at the Chicago Museum of Science & Industry

- Zephyr Patents—PDF reproductions of the patents developed for construction of the Pioneer Zephyr.

- [1]—Home of many more Burlington artifacts, including the Nebraska Zephyr trainset.

- "New Streamline Train Has Hit 125-Mile Speed", Popular Science, July 1934