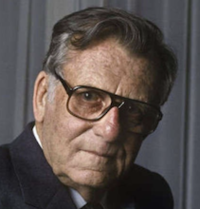

Morris West

Morris West | |

|---|---|

Morris West | |

| Born | Morris Langlo West 26 April 1916 St Kilda, Victoria, Australia |

| Died | 9 October 1999 (aged 83) Clareville, New South Wales, Australia |

| Pen name | Michael East, Julian Morris |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Period | 20th century |

| Genre | Literary fiction |

| Notable works | The Shoes of the Fisherman, The Devil's Advocate |

| Notable awards | James Tait Black Memorial prize 1959 |

Morris Langlo West AO (26 April 1916 – 9 October 1999) was an Australian novelist and playwright, best known for his novels The Devil's Advocate (1959), The Shoes of the Fisherman (1963) and The Clowns of God (1981). His books were published in 27 languages and sold more than 60 million copies worldwide. Each new book he wrote after he became an established writer sold more than one million copies.[1]

West's works were often focused on international politics and the role of the Roman Catholic Church in international affairs. In The Shoes of the Fisherman he described the election and career of a Slav as Pope, 15 years before the historic election of Karol Wojtyła as Pope John Paul II. The sequel, The Clowns of God, described a successor Pope who resigned the papacy to live in seclusion, 32 years before the abdication of Pope Benedict XVI in 2013.

Early life

[edit]West was born in St Kilda, Victoria, the son of a commercial salesman. Due to the large size of his family, he was sent to live with his grandparents. He attended the Christian Brothers College, St Kilda where he was awarded the prize of Dux by Archbishop Daniel Mannix in 1929.

At the age of 14, West entered the Congregation of Christian Brothers community at St Patricks in Strathfield, Sydney, "as a kind of refuge" from a difficult childhood.[2]

In 1934 he began teaching at St Thomas's Primary School, Lewisham, living in that community until 1936. He taught at schools in Tasmania and New South Wales between 1937 and 1939, while also studying at the University of Tasmania.

He left the Christian Brothers order in 1940. He worked as a salesman and a teacher.

War service

[edit]In April 1941, West enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force. He was commissioned as a lieutenant and worked as a cipher officer, being eventually posted to Gladesville, New South Wales, in 1944. He was seconded from the RAAF to work for Billy Hughes, former Australian prime minister, for a time.

His first published novel, Moon in My Pocket, came out in 1945 using the pseudonym "Julian Morris". He wrote it while in the air force. It was published by the Australasian Publishing Company, a branch of Harrap's Publishing Company in London, and sold more than 10,000 copies.[3][4]

Radio producer

[edit]West worked as publicity manager at Melbourne radio station 3DB. He moved into radio drama, setting up his own radio production company ARP, which operated from 1945 to 1954. For the next 10 years he focused on writing, directing and producing radio plays and serials.

His radio plays included The Mask of Marius Melville (1945), The Curtain Rises (1946),[5] The Affairs of Harlequin (1951), The Prince of Peace (c. 1951), When a Girl Marries (1952),[6] The Enchanted Island (1952), Trumpets in the Dawn (c. 1953–54) and Genesis in Juddsville (c. 1955–56).

The workload of his job and a crisis in his marital relations led to West having a nervous breakdown. He ultimately sold his company to focus on writing full-time.[7]

Novelist

[edit]Early works

[edit]West's first novel published under his own name was Gallows on the Sand (1955), written in seven days. He followed it with Kundu (1956), a New Guinea adventure written in three weeks.[7] He also wrote a play, The Illusionists (1955).

West moved to Europe with his family. His third novel was The Big Story (1957), which was later filmed as The Crooked Road (1965).

A trip to Naples led to meeting Father Borrelli who worked with the street boys of Naples. This resulted in the non-fiction book Children of the Sun (1957) which was West's first international success.[7][8] According to a later profile on the author:

With this work, West not only found his way as a writer but discovered the theme that would underpin almost all of his subsequent books — the nature and misuse of power. Of the 18 novels he was to write post-1957, 15 are on this subject. This discovery was particularly felicitous for West because, it suited his talents admirably. An interesting comparison may be made with David Williamson, another writer from whom profound thinking and significant insights are not to be expected. What they have in common is a keen eye for the real world around them. By fleshing out the partially familiar, they make perceptive sense of it, demonstrating in the process that the general uneasiness and suspicion ordinary people feel about many aspects of contemporary life are well-founded. West was to show that he could identify these concerns with considerable acuity.[9]

He wrote The Second Victory (1958) (also known as Backlash and later filmed) and under the pseudonym "Michael East" wrote McCreary Moves In (1958) aka The Concubine.

Best-selling novelist

[edit]West's first best-selling novel was The Devil's Advocate (1959) which he spent two years writing.[10] He sold the film rights for $250,000 and it was adapted into a play and later a film.[7] West later said the novel earned him several million dollars.[8]

He wrote another "Michael East" novel, The Naked Country (1960), which was filmed in the 1980s. Daughter of Silence (1961) was also adapted into a play.

During this time he was the Vatican correspondent for the Daily Mail from 1956 to 1963.[11] His son, C. Chris O'Hanlon, said that he spent his first 12 birthdays in 12 different countries.[12]

The Shoes of the Fisherman (1963) was a huge success, selling over six million copies and made into a movie.[13]

He followed it with The Ambassador (1965), The Tower of Babel (1968), Summer of the Red Wolf (1971)[14] and The Salamander (1973). He wrote a non-fiction book, Scandal in the Assembly: A Bill of Complaints and a Proposal for Reform of the Matrimonial Laws and Tribunals of the Roman Catholic Church (1970, with Robert Francis).

He wrote a play The Heretic, based on Giordano Bruno, which was performed on the London stage in 1973. Further novels included Harlequin (1974), The Navigator (1976),[15] Proteus (1979) and The Clowns of God (1981).[16] In 1978 he was living in England, New York and Italy and said "I'm an Australian by origin, by identity, in manners. I have never felt any destruction or diminution of my identity by having a European education, or by acquiring a fluency in three languages and living abroad."[17] His advance of Clowns of God was £100,000.[18] By 1981 his books had sold over 25 million copies.[19]

West wrote the play The World is Made of Glass in 1982 for the Adelaide Festival. He turned this into a novel which was published the following year.[7]

Return to Australia

[edit]In 1982 West returned home to Australia. His later novels include Cassidy (1986) (which became a mini series), Masterclass (1988), Lazarus (1990), The Ringmaster (1991), and The Lovers (1993).[20]

In 1993, West announced that he had written his last book and a formal valedictory dinner was held in his honour. However, he found he could not retire as he had planned and wrote a further three novels and two non-fiction books: Vanishing Point (1996) and Eminence (1998), plus an anthology entitled Images and Inscriptions (1997) and his memoir A View from the Ridge: The Testimony of a Twentieth-century Pilgrim (1996).[21][22]

He was working on the novel The Last Confession when he died; it was posthumously published in 2000.

Writing

[edit]A major theme of much of West's work was a question: when so many organisations use extreme violence towards evil ends, when and under what circumstances is it morally acceptable for their opponents to respond with violence? He stated on different occasions that his novels all deal with the same aspect of life, that is, the dilemma when sooner or later you have a situation such that nobody can tell you what to do.[23]

West wrote with little revision. His first longhand version was usually not very different from the final printed version.[22] Despite winning many prizes and being awarded honorary doctorates,[24] his commercial success and his skills as a story teller, he never won the acceptance of Australia's literary clique. In the 1998 Oxford Literary History of Australia it was stated that: "Despite his international popularity, West has been surprisingly neglected by Australian literary critics." The previous edition, edited by Dame Leonie Kramer, did not mention him at all.[1]

West was awarded the 1959 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for The Devil's Advocate. In the early 1960s, he helped found the Australian Society of Authors.[1] He presented the 1986 Playford Lecture.[23]

Personal life

[edit]West was born on 26 April 1916, in St Kilda. He and his first wife, Elizabeth Harvey, had two children: Elizabeth, who became a nun, and Julian who was a wine-maker before his death in 2005. Julian and his wife Helen Grimaux, had a daughter named Juliana Harriett West.

West and Elizabeth Harvey divorced, and West then married Joyce "Joy" Lawford. Since his first wife, Elizabeth, was still alive when he married Joy, he struggled for a church annulment of his first marriage. He was out of communion with the Roman Catholic Church for many years because of this marital situation, and he had significant issues with the church's teachings. However, he never considered himself as anything other than a committed Catholic. Joy West said that he was a believer who attended Mass every Sunday.[22]

West and Joy had four children together. One son, C. Chris O'Hanlon, born in 1954, changed his name at the age of 26 as a gesture of independence. After starting four books in an attempt to realise what he believed were his father's expectations, and having to give back the advances he received from publishers when he could not finish them, he realised that he was not destined to be a writer. O'Hanlon, who suffers from a severe bipolar disorder, founded Spike Wireless, an internet design house.[12]

Another of West's sons, Mike, is a musician who fronted the UK independent popular music band Man from Delmonte during the late 1980s and early 1990s and has released several solo albums of New Orleans country music, especially being well known with the international touring act Truckstop Honeymoon.

West's grandson Anthony (Ant) West is also a musician, who fronted the UK music band Futures and currently is in the UK group Oh Wonder.

West died at the age of 83 on 9 October 1999 in Clareville, New South Wales.

Honours

[edit]West was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia in the Australia Day Honours of 1985.[25] He was upgraded to Officer of the Order in the Queen's Birthday Honours of 1997.[26]

Bibliography

[edit]Fiction

[edit]- Moon in My Pocket (1945, using the pseudonym "Julian Morris")

- Gallows on the Sand (1956)

- Kundu (1956)

- The Big Story (1957; aka The Crooked Road)

- The Second Victory (1958; aka Backlash)

- McCreary Moves In (1958, using the pseudonym "Michael East"; aka The Concubine)

- The Devil's Advocate (1959)

- The Naked Country (1960, using the pseudonym "Michael East")

- Daughter of Silence (1961)

- The Shoes of the Fisherman (1963)

- The Ambassador (1965)

- The Tower of Babel (1968)

- Summer of the Red Wolf (1971)

- The Salamander (1973)

- Harlequin (1974; aka The Duel of Death)

- The Navigator (1976)

- Proteus (1979)

- The Clowns of God (1981)

- The World Is Made of Glass (1983)

- Cassidy (1986)

- Masterclass (1988)

- Lazarus (1990)

- The Ringmaster (1991)

- The Lovers (1993)

- Vanishing Point (1996)

- Eminence (1998)

- The Last Confession (2000, posthumously published)

Radio serials

[edit]- The Mask of Marius Melville (1945)[27]

- The Prince of Peace (c1951)[28]

- Trumpets in the Dawn (c1953–54)[28]

- Genesis in Juddsville (c1955–56)[29]

Radio dramas

[edit]- episode of Deadline

Plays

[edit]- The Illusionists (1955)

- The Devil's Advocate (1961)

- Daughter of Silence (1962)

- The Heretic (1969)

- The World is Made of Glass (1982)

Non-fiction

[edit]- Children of the Sun: The Slum Dwellers of Naples (1957) (US title: Children of the Shadows: The True Story of the Street Urchins of Naples)

- Scandal in the Assembly: A Bill of Complaints and a Proposal for Reform of the Matrimonial Laws and Tribunals of the Roman Catholic Church (1970, with Robert Francis)

- West, Morris (1996). A View from the Ridge: The Testimony of a Twentieth-century Pilgrim. Sydney: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-7322-5757-3.

- West, Morris (1997). Images & Inscriptions. Selected and arranged by Beryl Barraclough. Sydney: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-7322-5827-8.

Film adaptations

[edit]- The Crooked Road (based on The Big Story) (1965) starring Robert Ryan

- The Shoes of the Fisherman (1968) starring Anthony Quinn

- The Devil's Advocate (1977) starring John Mills, Daniel Massey, Paola Pitagora and Stéphane Audran

- The Salamander (1981)

- The Naked Country (1984)

- The Second Victory (1986)

- Cassidy (1989)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Sally Blakeney, "The outsider: How the literati shunned a luminary", Weekend Australian, 16–17 October 1999

- ^ Honan, William H., "Morris West, Popular Novelist Focusing on Faith, Dies at 83", New York Times, 12 October 1999.

- ^ "Saturday MAGAZINE". The Canberra Times. 6 August 1994. p. 43. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ ""Moon in My Pocket", by Julian Morris.—Australasian Publishing Co. Pty. Ltd., Sydney". The Sydney Morning Herald. 29 September 1945. p. 7. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Radio Humour of Himalayas". The Advocate. Melbourne. 16 January 1946. p. 18. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "GEORGE HART'S Radio Round- up". The Sun (LATE FINAL EXTRA ed.). New South Wales, Australia. 10 October 1952. p. 10. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ a b c d e "WRITERS' WORLD". The Canberra Times. 20 August 1983. p. 12. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "FEATURES". The Canberra Times. 10 September 1994. p. 47. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ Missen, Mollie (20 February 1993). "A master storyteller signs off". Sydney Morning Herald. p. 44.

- ^ "The Australian Novelists I. MORRIS WEST". The Bulletin. 18 January 1961. p. 18.

- ^ Janet Chimonyo, "Vatican tag", Weekend Australian, 13–14 June 1998,

- ^ a b Jane Wheatley, interviewer, "The two of us: Morris West and C. Chris O'Hanlon", Sydney Morning Herald, Good Weekend, 14 February 1998

- ^ Davies, Hunter (1 September 1981). "Morris West: the monk from Melbourne identifier". The Bulletin. p. 72.

- ^ "West in the isles". The Canberra Times. 9 October 1971. p. 15. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ ""I've always wanted to do a musical"". The Australian Women's Weekly. Australia. 25 February 1976. p. 13. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Morris West on the millennium". The Canberra Times. 24 April 1985. p. 14. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "The obsession of Morris West". The Canberra Times. 28 March 1978. p. 13. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "LIFE STYLE". The Canberra Times. 22 April 1981. p. 29. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Morris West talks about his new book... and hopes he's lost the gift of prophecy". The Australian Women's Weekly. Australia. 18 March 1981. p. 13. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "MAGAZINE: BOOKS". The Canberra Times. 13 March 1993. p. 9 (Saturday Magazine). Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Morris West 'rewarded amply' for Ms work". The Canberra Times. 16 November 1988. p. 10. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ a b c Tony Stephens, "Last Writes'", Sydney Morning Herald, Spectrum, 3 June 2000

- ^ a b Maryanne Confoy, "Morris the maverick", Weekend Australian, 5–6 March 2005

- ^ Ramona Koval, "Academics, we want to feel your passion!", Weekend Australian, 16–17 October 1999

- ^ "It's an Honour: AM". Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "It's an Honour: AO". Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Rodney Wetherell, "Robert Peach, Broadcaster, 1923–2004", Sydney Morning Herald, 28 January 2004

- ^ a b Australian Radio Series 1930–1970 Archived 9 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Albert Moran and Chris Keating, The A to Z of Australian Radio and Television. Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press, 2007, p. 383

External links

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Confoy, Maryanne (2005). Morris West: Literary Maverick. Milton, Queensland: John Wiley. ISBN 1-74031-119-1.

- Morris West

- 1916 births

- 1999 deaths

- Australian radio writers

- Australian male dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century Australian non-fiction writers

- Australian male novelists

- Australian Roman Catholics

- James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients

- Officers of the Order of Australia

- University of Melbourne alumni

- Writers from Melbourne

- Australian Catholic University alumni

- 20th-century Australian novelists

- 20th-century Australian dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century Australian male writers

- Royal Australian Air Force personnel of World War II

- Royal Australian Air Force officers

- People from St Kilda, Victoria

- Military personnel from Melbourne

- People educated at St Mary's College, Melbourne