Database model

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2017) |

A database model is a type of data model that determines the logical structure of a database. It fundamentally determines in which manner data can be stored, organized and manipulated. The most popular example of a database model is the relational model, which uses a table-based format.

Types

[edit]Common logical data models for databases include:

- This is the oldest form of database model. It was developed by IBM for IMS (information Management System), and is a set of organized data in tree structure. DB record is a tree consisting of many groups called segments. It uses one-to-many relationships, and the data access is also predictable.

- Network model

- Relational model

- Entity–relationship model

- Object model

- Document model

- Entity–attribute–value model

- Star schema

An object–relational database combines the two related structures.

Physical data models include:

Other models include:

Relationships and functions

[edit]A given database management system may provide one or more models. The optimal structure depends on the natural organization of the application's data, and on the application's requirements, which include transaction rate (speed), reliability, maintainability, scalability, and cost. Most database management systems are built around one particular data model, although it is possible for products to offer support for more than one model.

Various physical data models can implement any given logical model. Most database software will offer the user some level of control in tuning the physical implementation, since the choices that are made have a significant effect on performance.

A model is not just a way of structuring data: it also defines a set of operations that can be performed on the data.[1] The relational model, for example, defines operations such as select (project) and join. Although these operations may not be explicit in a particular query language, they provide the foundation on which a query language is built.

Flat model

[edit]

The flat (or table) model consists of a single, two-dimensional array of data elements, where all members of a given column are assumed to be similar values, and all members of a row are assumed to be related to one another. For instance, columns for name and password that might be used as a part of a system security database. Each row would have the specific password associated with an individual user. Columns of the table often have a type associated with them, defining them as character data, date or time information, integers, or floating point numbers. This tabular format is a precursor to the relational model.

Early data models

[edit]These models were popular in the 1960s, 1970s, but nowadays can be found primarily in old legacy systems. They are characterized primarily by being navigational with strong connections between their logical and physical representations, and deficiencies in data independence.

Hierarchical model

[edit]

In a hierarchical model, data is organized into a tree-like structure, implying a single parent for each record. A sort field keeps sibling records in a particular order. Hierarchical structures were widely used in the early mainframe database management systems, such as the Information Management System (IMS) by IBM, and now describe the structure of XML documents. This structure allows one-to-many relationship between two types of data. This structure is very efficient to describe many relationships in the real world; recipes, table of contents, ordering of paragraphs/verses, any nested and sorted information.

This hierarchy is used as the physical order of records in storage. Record access is done by navigating downward through the data structure using pointers combined with sequential accessing. Because of this, the hierarchical structure is inefficient for certain database operations when a full path (as opposed to upward link and sort field) is not also included for each record. Such limitations have been compensated for in later IMS versions by additional logical hierarchies imposed on the base physical hierarchy.

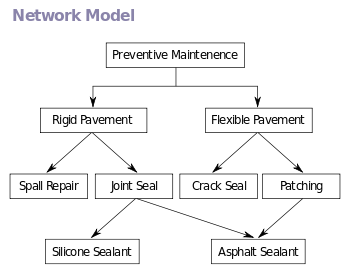

Network model

[edit]

The network model expands upon the hierarchical structure, allowing many-to-many relationships in a tree-like structure that allows multiple parents. It was most popular before being replaced by the relational model, and is defined by the CODASYL specification.

The network model organizes data using two fundamental concepts, called records and sets. Records contain fields (which may be organized hierarchically, as in the programming language COBOL). Sets (not to be confused with mathematical sets) define one-to-many relationships between records: one owner, many members. A record may be an owner in any number of sets, and a member in any number of sets.

A set consists of circular linked lists where one record type, the set owner or parent, appears once in each circle, and a second record type, the subordinate or child, may appear multiple times in each circle. In this way a hierarchy may be established between any two record types, e.g., type A is the owner of B. At the same time another set may be defined where B is the owner of A. Thus all the sets comprise a general directed graph (ownership defines a direction), or network construct. Access to records is either sequential (usually in each record type) or by navigation in the circular linked lists.

The network model is able to represent redundancy in data more efficiently than in the hierarchical model, and there can be more than one path from an ancestor node to a descendant. The operations of the network model are navigational in style: a program maintains a current position, and navigates from one record to another by following the relationships in which the record participates. Records can also be located by supplying key values.

Although it is not an essential feature of the model, network databases generally implement the set relationships by means of pointers that directly address the location of a record on disk. This gives excellent retrieval performance, at the expense of operations such as database loading and reorganization.

Popular DBMS products that utilized it were Cincom Systems' Total and Cullinet's IDMS. IDMS gained a considerable customer base; in the 1980s, it adopted the relational model and SQL in addition to its original tools and languages.

Most object databases (invented in the 1990s) use the navigational concept to provide fast navigation across networks of objects, generally using object identifiers as "smart" pointers to related objects. Objectivity/DB, for instance, implements named one-to-one, one-to-many, many-to-one, and many-to-many named relationships that can cross databases. Many object databases also support SQL, combining the strengths of both models.

Inverted file model

[edit]In an inverted file or inverted index, the contents of the data are used as keys in a lookup table, and the values in the table are pointers to the location of each instance of a given content item. This is also the logical structure of contemporary database indexes, which might only use the contents from a particular columns in the lookup table. The inverted file data model can put indexes in a set of files next to existing flat database files, in order to efficiently directly access needed records in these files.

Notable for using this data model is the ADABAS DBMS of Software AG, introduced in 1970. ADABAS has gained considerable customer base and exists and supported until today. In the 1980s it has adopted the relational model and SQL in addition to its original tools and languages.

Document-oriented database Clusterpoint uses inverted indexing model to provide fast full-text search for XML or JSON data objects for example.

Relational model

[edit]The relational model was introduced by E.F. Codd in 1970[2] as a way to make database management systems more independent of any particular application. It is a mathematical model defined in terms of predicate logic and set theory, and implementations of it have been used by mainframe, midrange and microcomputer systems.

The products that are generally referred to as relational databases in fact implement a model that is only an approximation to the mathematical model defined by Codd. Three key terms are used extensively in relational database models: relations, attributes, and domains. A relation is a table with columns and rows. The named columns of the relation are called attributes, and the domain is the set of values the attributes are allowed to take.

The basic data structure of the relational model is the table, where information about a particular entity (say, an employee) is represented in rows (also called tuples) and columns. Thus, the "relation" in "relational database" refers to the various tables in the database; a relation is a set of tuples. The columns enumerate the various attributes of the entity (the employee's name, address or phone number, for example), and a row is an actual instance of the entity (a specific employee) that is represented by the relation. As a result, each tuple of the employee table represents various attributes of a single employee.

All relations (and, thus, tables) in a relational database have to adhere to some basic rules to qualify as relations. First, the ordering of columns is immaterial in a table. Second, there can not be identical tuples or rows in a table. And third, each tuple will contain a single value for each of its attributes.

A relational database contains multiple tables, each similar to the one in the "flat" database model. One of the strengths of the relational model is that, in principle, any value occurring in two different records (belonging to the same table or to different tables), implies a relationship among those two records. Yet, in order to enforce explicit integrity constraints, relationships between records in tables can also be defined explicitly, by identifying or non-identifying parent-child relationships characterized by assigning cardinality (1:1, (0)1:M, M:M). Tables can also have a designated single attribute or a set of attributes that can act as a "key", which can be used to uniquely identify each tuple in the table.

A key that can be used to uniquely identify a row in a table is called a primary key. Keys are commonly used to join or combine data from two or more tables. For example, an Employee table may contain a column named Location which contains a value that matches the key of a Location table. Keys are also critical in the creation of indexes, which facilitate fast retrieval of data from large tables. Any column can be a key, or multiple columns can be grouped together into a compound key. It is not necessary to define all the keys in advance; a column can be used as a key even if it was not originally intended to be one.

A key that has an external, real-world meaning (such as a person's name, a book's ISBN, or a car's serial number) is sometimes called a "natural" key. If no natural key is suitable (think of the many people named Brown), an arbitrary or surrogate key can be assigned (such as by giving employees ID numbers). In practice, most databases have both generated and natural keys, because generated keys can be used internally to create links between rows that cannot break, while natural keys can be used, less reliably, for searches and for integration with other databases. (For example, records in two independently developed databases could be matched up by social security number, except when the social security numbers are incorrect, missing, or have changed.)

The most common query language used with the relational model is the Structured Query Language (SQL).

Dimensional model

[edit]The dimensional model is a specialized adaptation of the relational model used to represent data in data warehouses in a way that data can be easily summarized using online analytical processing, or OLAP queries. In the dimensional model, a database schema consists of a single large table of facts that are described using dimensions and measures. A dimension provides the context of a fact (such as who participated, when and where it happened, and its type) and is used in queries to group related facts together. Dimensions tend to be discrete and are often hierarchical; for example, the location might include the building, state, and country. A measure is a quantity describing the fact, such as revenue. It is important that measures can be meaningfully aggregated—for example, the revenue from different locations can be added together.

In an OLAP query, dimensions are chosen and the facts are grouped and aggregated together to create a summary.

The dimensional model is often implemented on top of the relational model using a star schema, consisting of one highly normalized table containing the facts, and surrounding denormalized tables containing each dimension. An alternative physical implementation, called a snowflake schema, normalizes multi-level hierarchies within a dimension into multiple tables.

A data warehouse can contain multiple dimensional schemas that share dimension tables, allowing them to be used together. Coming up with a standard set of dimensions is an important part of dimensional modeling.

Its high performance has made the dimensional model the most popular database structure for OLAP.

Post-relational database models

[edit]Products offering a more general data model than the relational model are sometimes classified as post-relational.[3] Alternate terms include "hybrid database", "Object-enhanced RDBMS" and others. The data model in such products incorporates relations but is not constrained by E.F. Codd's Information Principle, which requires that

all information in the database must be cast explicitly in terms of values in relations and in no other way

— [4]

Some of these extensions to the relational model integrate concepts from technologies that pre-date the relational model. For example, they allow representation of a directed graph with trees on the nodes. The German company sones implements this concept in its GraphDB.

Some post-relational products extend relational systems with non-relational features. Others arrived in much the same place by adding relational features to pre-relational systems. Paradoxically, this allows products that are historically pre-relational, such as PICK and MUMPS, to make a plausible claim to be post-relational.

The resource space model (RSM) is a non-relational data model based on multi-dimensional classification.[5]

Graph model

[edit]Graph databases allow even more general structure than a network database; any node may be connected to any other node.

Multivalue model

[edit]Multivalue databases are "lumpy" data, in that they can store exactly the same way as relational databases, but they also permit a level of depth which the relational model can only approximate using sub-tables. This is nearly identical to the way XML expresses data, where a given field/attribute can have multiple right answers at the same time. Multivalue can be thought of as a compressed form of XML.

An example is an invoice, which in either multivalue or relational data could be seen as (A) Invoice Header Table - one entry per invoice, and (B) Invoice Detail Table - one entry per line item. In the multivalue model, we have the option of storing the data as on table, with an embedded table to represent the detail: (A) Invoice Table - one entry per invoice, no other tables needed.

The advantage is that the atomicity of the Invoice (conceptual) and the Invoice (data representation) are one-to-one. This also results in fewer reads, less referential integrity issues, and a dramatic decrease in the hardware needed to support a given transaction volume.

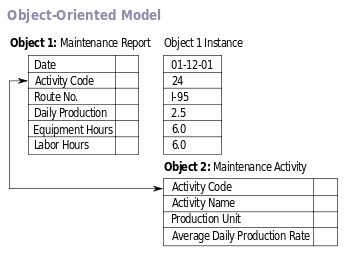

Object-oriented database models

[edit]

In the 1990s, the object-oriented programming paradigm was applied to database technology, creating a new database model known as object databases. This aims to avoid the object–relational impedance mismatch – the overhead of converting information between its representation in the database (for example as rows in tables) and its representation in the application program (typically as objects). Even further, the type system used in a particular application can be defined directly in the database, allowing the database to enforce the same data integrity invariants. Object databases also introduce the key ideas of object programming, such as encapsulation and polymorphism, into the world of databases.

A variety of these ways have been tried for storing objects in a database. Some[which?] products have approached the problem from the application programming end, by making the objects manipulated by the program persistent. This typically requires the addition of some kind of query language, since conventional programming languages do not have the ability to find objects based on their information content. Others[which?] have attacked the problem from the database end, by defining an object-oriented data model for the database, and defining a database programming language that allows full programming capabilities as well as traditional query facilities.

Object databases suffered because of a lack of standardization: although standards were defined by ODMG, they were never implemented well enough to ensure interoperability between products. Nevertheless, object databases have been used successfully in many applications: usually specialized applications such as engineering databases or molecular biology databases rather than mainstream commercial data processing. However, object database ideas were picked up by the relational vendors and influenced extensions made to these products and indeed to the SQL language.

An alternative to translating between objects and relational databases is to use an object–relational mapping (ORM) library.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Elmasri, Ramez; Navathe, Shamkant (2016). Fundamentals of database systems (Seventh ed.). p. 33. ISBN 9780133970777.

- ^ E.F. Codd (1970). "A relational model of data for large shared data banks". In: Communications of the ACM archive. Vol 13. Issue 6(June 1970). pp.377-387.

- ^ Introducing databases by Stephen Chu, in Conrick, M. (2006) Health informatics: transforming healthcare with technology, Thomson, ISBN 0-17-012731-1, p. 69.

- ^ Date, C. J. (June 1, 1999). "When's an extension not an extension?". Intelligent Enterprise. 2 (8).

- ^ Zhuge, H. (2008). The Web Resource Space Model. Web Information Systems Engineering and Internet Technologies Book Series. Vol. 4. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-72771-4.