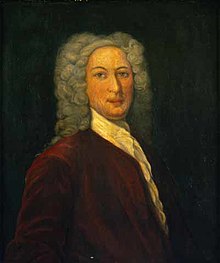

Philip Livingston (1686–1749)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2014) |

Philip Livingston | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd Lord of Livingston Manor | |

| In office 1728 – 1749 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Livingston the Elder |

| Succeeded by | Robert Livingston |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 9, 1686 Albany, New York, English America |

| Died | February 11, 1749 (aged 62) New York, British America |

| Spouse |

Catherine Van Brugh (m. 1708) |

| Children | 11, including Robert, Peter, Philip and William |

| Parent(s) | Robert Livingston Alida Schulyer van Rensselaer |

| Relatives | Robert Livingston (brother) Pieter Van Brugh (father-in-law) |

| Occupation | Merchant, slave trader, politician |

Philip Livingston (July 9, 1686 – February 11, 1749) was an American merchant, slave trader and politician in colonial New York. The son of Robert Livingston the Elder and elder brother of Robert of Clermont, Philip was the second lord of Livingston Manor.

Early life

[edit]

Philip Livingston was the fourth child and second son of Robert Livingston and Alida (née Schuyler) van Rensselaer Livingston. He was born on July 9, 1686, in his father's Albany, New York town house, at "Elm Tree Corner", the intersection of State and Pearl Streets and one of early Albany's principal crossroads. The name commemorates a legendary elm tree that reputedly was planted in 1735 by a young Philip Livingston in front of his father's house on the northwestern corner. Something of an Albany landmark, the old elm was removed in June 1877.[1]

At the time of Philip's birth, his father was downriver in New York engaged in persuading Governor Dongan to grant a city charter to Albany. Philip was named for his maternal grandfather Philip Pieterse Schuyler.

Alida Livingston taught her children to read and write both English and Dutch. Philip spent a year with the Huguenot community of New Rochelle in order to learn French, in anticipation of a career as an Albany trader dealing with French Canada.[2] Philip grew up learning the intricacies of business, and trade from his father, the most successful entrepreneur in the Hudson Valley.[3] From 1707, he acted as his father's unofficial deputy in the offices of clerk of the county and city of Albany.[2] Philip Livingston is described as "a handsome, gay 'breaker of hearts'".[4]

Career

[edit]Merchant

[edit]His parents relocated to Livingston Manor sometime prior to Philip's marriage Catherine van Brugh in 1708. Philip and his wife took up residence in the Albany townhouse. From there he took over management of his father's Albany enterprises. Philip Livingston began his mercantile career at the age of 23 after an apprenticeship with one of his Schuyler uncles in Albany. Later, he became a mercantile factor in his own right, trading furs with New York merchants such as Stephen DeLancey and Henry Cuyler. With vast land tracts and abundant water resources at their disposal, the Livingstons were well placed to recognize the importance of grain as a commodity New York could export. Robert Livingston built two gristmills on the Manor and Philip Livingston acted as his father's agent buying grain in the Hudson valley and selling flour in New York or shipping it the British West Indies. His younger brother, Robert, served as his agent in New York City.

Early in his career, Philip Livingston surveyed land titles. In late 1719, he was licensed to practice law.[3] In 1720 Philip was appointed one of the Commissioners for Indian Affairs. That same year Robert Livingston resigned the positions of Secretary for the Commission of Indian Affairs, and Town Clerk of Albany in favor of Philip. The appointment was confirmed by Governor Burnet.[5] The position of Secretary to the Commission of Indian Affairs Robert put to good advantage in acquiring thousands of acres of unimproved land in the Mohawk Valley.[2] In 1725, Philip was appointed to the Provincial Council, a position he held until his death.

Unlike his father, Philip preferred business to politics, and considered himself primarily a merchant. In 1724 he declined a seat in the assembly as he thought attending the legislature would hurt business.[2]

Philip Livingston spent a good deal of time in New York city where he owned a townhouse on Broad Street.[5] Livingston also owned ships and participated with his sons in lucrative privateering and Triangular Trade operations.

Slave trade

[edit]Philip Livingston inherited slaves from both his parents and in-laws. One of Robert Livingston's earliest investments in 1690 was a half-interest in the Margriet, a slave ship that journeyed to Madagascar, Barbados, and Virginia to trade in slaves, sugar, and tobacco. Philip and his sons continued this lucrative trade. Philip traded extensively with the West Indies; in the 1730s and 1740s, he was one of New York's leading importers of slave labor from the sugar islands.[6]

Philip formed a company with his sons Philip and Pieter Van Brugh Livingston, called Philip Livingston & Sons, New York. At first the Livingstons imported small numbers of slaves from Antigua and Jamaica.[7] One of the most notorious open-air markets was along the East River at the end of Wall Street.[8] In August 1733, Philip's sloop Katherine returned with fifty blacks from Jamaica. In 1738, Philip bought a one-third share in a voyage to Guinea, where two hundred slaves were purchased and consigned to his son Peter Van Brugh and his partner in Jamaica. The ships also handled gold and ivory. The ship Oswego out of Jamaica, arrived in New York in August 1741, carrying a consignment of twelve African slaves.[8] Slave ships continued to arrive in port despite the panic caused that summer by a so-called slave insurrection in the city. In 1749, the sloop Rhode Island, owned by the company Philip Livingston & Sons, traded rum, tobacco and cheese for guns, cloth and ivory, which it then traded on the African coast for 124 slaves.[9] In 1750 Livingston & Sons had three vessels working the African coast. They also owned shares in the Stork and the Sarah and Elizabeth.[7] When the Wolf docked in New York Harbor in May 1751, 66 slaves had survived the voyage out of 147 boarded.[6][10]

One Livingston Manor tenant farmer, John Dykeman, was murdered in 1715 by his slave, Ben. Coming in the aftermath of the New York Slave Revolt of 1712, it was first thought to be part of another such uprising. But after a preliminary hearing conducted by Robert Livingston, Sr. and some county magistrates, it was determined that the murder was the sole act of a heartbroken, vengeful father: Dykeman had sold Ben's daughter off the manor to one of Livingston's kin in New York City.[8]

Lord of Livingston Manor

[edit]Robert Livingston, first Lord of the Manor died on October 1, 1728. As Philip's older brother Johannes had died in 1720, Philip succeeded as second Lord of Livingston Manor.[3] He was well prepared, having assisted his father in the management of the estate. He increased the family's real estate holdings and in 1743 establishing the colony's first iron works at Ancram, named for a village in Scotland. Livingston Manor became an integrated agricultural, mercantile and industrial concern. However, business affairs kept him in Albany, where he was clerk of the county and city.

In 1737, he was appointed to the commission to set the boundary between Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

Personal life

[edit]In September 1708, Livingston married nineteen-year-old Catherine Van Brugh, the only child of Albany mayor Pieter Van Brugh. Three months later, the first of their eleven children was baptized in the Albany Dutch church.[11] Livingston trained his sons for the mercantile profession, sending them into apprenticeship with merchant friends and correspondents in New York, London and Jamaica. The children were:[12]

- Robert Livingston (1708–1790), the 3rd Lord of the Manor who married Maria Thong (1711–1765), a granddaughter of Gov. Rip Van Dam. After her death, he married Gertrude (née Van Rensselaer) Schuyler (b. 1714), daughter of Kiliaen Van Rensselaer.

- Pieter Livingston (b. 1710), who died young.[12]

- Peter Van Brugh Livingston (1712–1792), who married Mary Alexander (1721–1767), the daughter of James Alexander and Mary Spratt Provoost.[12]

- John Livingston (1714–1786), who married Catharine de Peyster (1724–1804), a granddaughter of the Mayor of New York City Abraham de Peyster.[12]

- Philip Livingston (1716–1778), a signer of the Declaration of Independence who married Christina Ten Broeck (1718–1801), daughter of Albany Mayor Dirck Ten Broeck.[12]

- Hendrick "Henry" Livingston (1719–1772), who lived and died in the Jamaica, West Indies.[12]

- Sara Livingston (1721–1722), who died young.[12]

- William Livingston (1723–1790), a signer of the United States Constitution and the first Governor of New Jersey, who married Susannah French (1723–1789) in 1745.[13]

- Sarah Livingston (1725–1805), who married William Alexander, Lord Stirling (1726–1783), in 1748.[12]

- Alida Livingston (1728–1790), who married Henry Hansen (d. 1758). After his death, she married Martinus Hoffman (1706–1772), a member of the Hoffman family and the father-in-law of New York State Senator Isaac Roosevelt.[14]

- Catherine Livingston (1733–1807),[15] who married Alderman John Lawrence (1721–1764) of New York in 1759.[12] After his early death, Catherine, who did not have children, never remarried.[15]

Philip Livingston died in New York on February 11, 1749. His body was transported upriver and buried at Livingston Memorial Church and Burial Ground in Livingston Manor.[5]

Philanthropy

[edit]He donated 28 pounds sterling to Yale College in 1745 "as a small acknowledgement of the sense I have for the favour and Education my sons have had there." The donation was used in 1756 by President Thomas Clap to establish the Livingstonian Professorship of Divinity.[16] The Livingston Gateway at Yale stands in his honor.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Bielinski, Stefan. "Elm Tree Corner", New York State Museum". Archived from the original on 2016-03-12. Retrieved 2014-07-06.

- ^ a b c d Kierner, Cynthia A., Traders and Gentlefolk: The Livingstons of New York, 1675-1790, Cornell University Press, 1992

- ^ a b c "Bielinski, Stefan. "Philip Livingston", New York State Museum". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2014-07-06.

- ^ The WPA Guide to New York, Federal Writers' Project

- ^ a b c Livingston, Edwin Brockholst. The Livingstons of Livingston Manor, Knickerbocker Press, 1910

- ^ a b c "First Endowed Professorship". www.yaleslavery.org. Yale University. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ a b The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History, University of Nebraska Press, Dec 1, 2005, Rawley, James A. and Behrendt, Stephen D.,

- ^ a b c "Williams-Myers, A.J., "Re-Examining Slavery in New York", New York State Archives, Vol.1, Number 3, Winter 2002". Archived from the original on 2015-03-30. Retrieved 2014-07-07.

- ^ Collins, Glenn. "The 'Main Event'", New York Times, The Arts, Tuesday, September 27, 2005

- ^ Marable, Manning (2006). Living Black History: How Reimagining the African-American Past Can Remake America's Racial Future. Basic Books. p. 8. ISBN 9780465043897. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ Bielinski, Stefan. "Catharina Van Brugh Livingston", New York State Museum

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Livingston, Edwin Brockholst (1910). The Livingstons of Livingston Manor: Being the History of that Branch of the Scottish House of Callendar which Settled in the English Province of New York During the Reign of Charles the Second; and Also Including an Account of Robert Livingston of Albany, "The Nephew," a Settler in the Same Province and His Principal Descendants. Knickerbocker Press. p. 551. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ "America's Founding Fathers – Delegates to the Constitutional Convention: New Jersey". U.S. National Archives & Records Administration. 30 October 2015. Archived from the original on June 6, 2016.

- ^ The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. New York Genealogical and Biographical Society. 1899. p. 224. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ a b Carver, Wees, Beth; Higgins, Harvey, Medill (2013). Early American Silver in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 257. ISBN 9781588394910. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [1] Archived July 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- Wilder, Craig Steven. Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America's Universities, Bloomsbury Press, New York

- "The First Endowed Professorship", Yale, Slavery & Abolition

|

- 1686 births

- 1749 deaths

- 18th-century American philanthropists

- American people of Scottish descent

- 18th-century American slave traders

- Benefactors of Yale University

- Burials in New York (state)

- Businesspeople from Albany, New York

- Livingston family

- People from colonial New York

- Philanthropists from New York (state)

- Schuyler family

- Van Brugh family

- Slave owners from the Thirteen Colonies

- Merchants from colonial New York