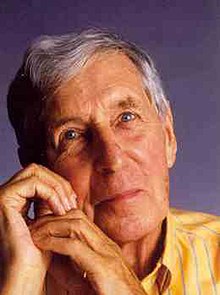

Michael Tippett

Sir Michael Kemp Tippett CH CBE (2 January 1905 – 8 January 1998) was an English composer who rose to prominence during and immediately after the Second World War. In his lifetime he was sometimes ranked with his contemporary Benjamin Britten as one of the leading British composers of the 20th century. Among his best-known works are the oratorio A Child of Our Time, the orchestral Fantasia Concertante on a Theme of Corelli, and the opera The Midsummer Marriage.

Tippett's talent developed slowly. He withdrew or destroyed his earliest compositions, and was 30 before any of his works were published. Until the mid-to-late 1950s his music was broadly lyrical in character, before changing to a more astringent and experimental style. New influences—including those of jazz and blues after his first visit to America in 1965—became increasingly evident in his compositions. While Tippett's stature with the public continued to grow, not all critics approved of these changes in style, some believing that the quality of his work suffered as a consequence. From around 1976 his late works began to reflect the works of his youth through a return to lyricism. Although he was much honoured in his lifetime, critical judgement on Tippett's legacy has been uneven, the greatest praise generally reserved for his earlier works. His centenary in 2005 was a muted affair; apart from the few best-known works, his music has not been performed frequently in the 21st century.

Having briefly embraced communism in the 1930s, Tippett avoided identifying with any political party. A pacifist after 1940, he was imprisoned in 1943 for refusing to carry out war-related duties required by his military exemption. His initial difficulties in accepting his homosexuality led him in 1939 to Jungian psychoanalysis; the Jungian dichotomy of "shadow" and "light" remained a recurring factor in his music. He was a strong advocate of music education, and was active for much of his life as a radio broadcaster and writer on music.

Life

[edit]Family background

[edit]The Tippett family originated in Cornwall. Michael Tippett's grandfather, George Tippett, left the county in 1854 to make his fortune in London through property speculation and other business schemes. A flamboyant character, he had a strong tenor voice that was a popular feature at Christian revivalist meetings. In later life his business enterprises faltered, leading to debts, prosecution for fraud, and a term of imprisonment. His son Henry, born in 1858, was Michael's father. A lawyer by training, he was successful in business and was independently wealthy by the time of his marriage in April 1903.[1] Unusually for his background and upbringing, Henry Tippett was a progressive liberal and a religious sceptic.[2]

Henry Tippett's bride was Isabel Kemp, from a large upper-middle-class family based in Kent. Among her mother's cousins was Charlotte Despard, a well-known campaigner for women's rights, suffragism, and Irish home rule. Despard was a powerful influence on the young Isabel, who was herself briefly imprisoned after participating in an illegal suffragette protest in Trafalgar Square. Though neither she nor Henry was musical, she had inherited an artistic talent from her mother, who had exhibited at the Royal Academy. After their marriage the couple settled outside London in Eastcote, where two sons were born—the second, Michael, on 2 January 1905.[3]

Childhood and schooling

[edit]

Shortly after Michael's birth, the family moved to Wetherden in Suffolk. Michael's education began in 1909 with a nursery governess and various private tutors who followed a curriculum that included piano lessons—his first formal contact with music.[4] There was a piano in the house, on which he "took to improvising crazily ... which I called 'composing', though I had only the vaguest notion of what that meant".[5] In September 1914 Michael became a boarder at Brookfield Preparatory School in Swanage, Dorset. He spent four years there, at one point earning notoriety by writing an essay that challenged the existence of God.[6][7] In 1918 he won a scholarship to Fettes College, a boarding school in Edinburgh, where he studied the piano, sang in the choir, and began to learn to play the pipe organ. The school was not a happy place; sadistic bullying of the younger pupils was commonplace.[8][9] When Michael revealed to his parents in March 1920 that he had formed a homosexual relationship with another boy, they removed him to Stamford School in Lincolnshire, where a decade previously Malcolm Sargent had been a pupil.[10][11]

Around this time Henry Tippett decided to live in France, and the house in Wetherden was sold. The 15-year-old Michael and his brother Peter remained at school in England, travelling to France for their holidays.[12] Michael found Stamford much more congenial than Fettes, and developed both academically and musically. He found an inspiring piano teacher in Frances Tinkler, who introduced him to the music of Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, and Chopin.[9] Sargent had maintained his connection with the school, and was present when Tippett and another boy played Bach's C minor Concerto for Two Harpsichords on pianos with a local string orchestra. Tippett sang in the chorus when Sargent directed a local performance of Robert Planquette's operetta Les Cloches de Corneville.[13] Despite his parents' wish that he follow an orthodox path by proceeding to Cambridge University, Tippett had firmly decided on a career as a composer, a prospect that alarmed them and was discouraged by his headmaster and by Sargent.[14]

By mid-1922 Tippett had developed a rebellious streak. His overt atheism particularly troubled the school, and he was required to leave. He remained in Stamford in private lodgings, while continuing lessons with Tinkler and with the organist of St Mary's Church.[14] He also began studying Charles Villiers Stanford's book Musical Composition, which, he later wrote, "became the basis of all my compositional efforts for decades to come".[15] In 1923 Henry Tippett was persuaded that some form of musical career, perhaps as a concert pianist, was possible, and agreed to support his son in a course of study at the Royal College of Music (RCM). After an interview with the college principal, Sir Hugh Allen, Tippett was accepted despite his lack of formal entry qualifications.[7][14][16]

Royal College of Music

[edit]

Tippett began at the RCM in the summer term of 1923, when he was 18 years old. At the time, his biographer Meirion Bowen records, "his aspirations were Olympian, though his knowledge rudimentary".[17] Life in London widened his musical awareness, especially the Proms at the Queen's Hall, opera at Covent Garden (where he saw Dame Nellie Melba's farewell performance in La bohème) and the Diaghilev Ballet. He heard Chaliapin sing, and attended concerts conducted by, among others, Stravinsky and Ravel—the last-named "a tiny man who stood bolt upright and conducted with what to me looked like a pencil".[18] Tippett overcame his initial ignorance of early music by attending Palestrina masses at Westminster Cathedral, following the music with the help of a borrowed score.[17]

At the RCM, Tippett's first composition tutor was Charles Wood, who used the models of Bach, Mozart and Beethoven to instil a solid understanding of musical forms and syntax. When Wood died in 1926, Tippett chose to study with C.H. Kitson, whose pedantic approach and lack of sympathy with Tippett's compositional aims strained the relationship between teacher and pupil.[19][n 1] Tippett studied conducting with Sargent and Adrian Boult, finding the latter a particularly empathetic mentor—he let Tippett stand with him on the rostrum during rehearsals and follow the music from the conductor's score.[17] By this means Tippett became familiar with the music of composers then new to him, such as Delius and Debussy,[20] and learned much about the sounds of orchestral instruments.[21]

In 1924 Tippett became the conductor of an amateur choir in the Surrey village of Oxted. Although he saw this initially as a means of advancing his knowledge of English madrigals, his association with the choir lasted many years. Under his direction it combined with a local theatrical group, the Oxted and Limpsfield Players, to give performances of Vaughan Williams's opera The Shepherds of the Delectable Mountains and of Tippett's own adaptation of an 18th-century ballad opera, The Village Opera.[22] He passed his Bachelor of Music (BMus) exams, at his second attempt, in December 1928. Rather than continuing to study for a doctorate, Tippett decided to leave the academic environment.[21] The RCM years had brought him intense and lasting friendships with members of both sexes, in particular with Francesca Allinson and David Ayerst.[21]

Early career

[edit]False start

[edit]On leaving the RCM, Tippett settled in Oxted to continue his work with the choir and theatrical group and to compose. To support himself he taught French at Hazelwood, a small preparatory school in Limpsfield, which provided him with a salary of £80 a year and a cottage. Also teaching at the school was Christopher Fry, the future poet and playwright who later collaborated with Tippett on several of the composer's early works.[23][24]

In February 1930 Tippett provided the incidental music for a performance by his theatrical group of James Elroy Flecker's Don Juan, and in October he directed them in his own adaptation of Stanford's opera The Travelling Companion. His compositional output was such that on 5 April 1930 he gave a concert in Oxted consisting entirely of his own works—a Concerto in D for flutes, oboe, horns and strings; settings for tenor of poems by Charlotte Mew; Psalm in C for chorus and orchestra, with a text by Christopher Fry; piano variations on the song "Jockey to the Fair"; and a string quartet.[25] Professional soloists and orchestral players were engaged, and the concert was conducted by David Moule-Evans, a friend from the RCM. Despite encouraging comments from The Times and the Daily Telegraph, Tippett was deeply dissatisfied with the works, and decided that he needed further tuition. He withdrew the music, and in September 1930 re-enrolled at the RCM for a special course of study in counterpoint with R. O. Morris, an expert on 16th-century music. This second RCM period, during which he learned to write fugues in the style of Bach and received additional tuition in orchestration from Gordon Jacob,[23] was central to Tippett's eventual discovery of what he termed his "individual voice".[22]

On 15 November 1931 Tippett conducted his Oxted choir in a performance of Handel's Messiah, using choral and orchestral forces close to Handel's original intentions. Such an approach was rare at that time, and the event attracted considerable interest.[23]

Friendships, politics and music

[edit]In mid-1932 Tippett moved to a cottage in neighbouring Limpsfield, provided by friends as a haven in which he could concentrate on composition.[26][n 2] His friendships with Ayerst and Allinson had opened up new cultural and political vistas. Through Ayerst he met W. H. Auden, who in due course introduced him to T. S. Eliot. Although no deep friendship developed with either poet, Tippett came to consider Eliot his "spiritual father".[28][29] Ayerst also introduced him to a young artist, Wilfred Franks. By this time Tippett was coming to terms with his homosexuality, while not always at ease with it. Franks provided him with what he called "the deepest, most shattering experience of falling in love".[30] This intense relationship ran alongside a political awakening. Tippett's natural sympathies had always been leftish, and became more consciously so from his inclusion in Allinson's circle of left-wing activists. As a result, he gave up his teaching position at Hazelwood to become the conductor of the South London Orchestra, a project financed by the London County Council and made up of unemployed musicians.[31] Its first public concert was held on 5 March 1933 at Morley College, later to become Tippett's professional base.[32]

"So God He made us outlaws

To beat the devil's man

To rob the rich, to help the poor

By Robin's ten-year plan."

Robin Hood, interpreted by Tippett as a hero of the 1930s class war[33]

In the summers of 1932 and 1934 Tippett took charge of musical activities at miners' work camps near Boosbeck in the north of England. Known as the Cleveland Work Camps, they were run by a munificent local landowner, Major Pennyman, to give unemployed miners a sense of purpose and independence. In 1932 Tippett arranged the staging of a shortened version of John Gay's The Beggar's Opera, with locals playing the main parts, and the following year he provided the music for a new folk opera, Robin Hood, with words by Ayerst, himself and Ruth Pennyman. Both works proved hugely popular with their audiences,[32][33] and although most of the music has disappeared, Tippett revived some of Robin Hood for use in his Birthday Suite for Prince Charles of 1948.[34][35] In October 1934 Tippett and the South London Orchestra performed at a centenary celebration of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, as part of a grand Pageant of Labour at the Crystal Palace.[28][36]

Tippett was not formally a member of any political party or group until 1935, when he joined the British Communist Party at the urging of his cousin, Phyllis Kemp. This membership was brief; the influence of Trotsky's History of the Russian Revolution had led him to embrace Trotskyism, while the party maintained a strict Stalinist line. Tippett resigned after a few months when he saw no chance of converting his local party to his Trotskyist views.[31][36] According to his obituarist J.J. Plant, Tippett then joined the Bolshevik-Leninist Group within the Labour Party, where he continued to advocate Trotskyism until at least 1938.[37] Although Tippett's radical instincts always remained strong, he was aware that excessive political activism would distract him from his overriding objective of becoming recognised as a composer.[7] A significant step towards professional recognition came in December 1935, when the Brosa Quartet performed his String Quartet No. 1 at the Mercury Theatre in Notting Hill, London. This work, which he dedicated to Franks,[38][39] is the first in the recognised canon of Tippett's music.[7] Throughout much of the 1930s Wilf Franks continued to be an important influence on Tippett both creatively and politically. Franks had a passion for the poetry of both William Blake and Wilfred Owen; Tippett claimed that Franks knew Owen's poetry 'almost word for word and draws it out for me, its meanings, its divine pity and so on...'.[40][41]

Towards maturity

[edit]Personal crisis

[edit]Before the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, Tippett released two further works: the Piano Sonata No. 1, first performed by Phyllis Sellick at the Queen Mary Hall, London, on 11 November 1938, and the Concerto for Double String Orchestra, which was not performed until 1940.[39] In a climate of increasing political and military tension, Tippett's compositional efforts were overwhelmed by an emotional crisis. When his relationship with Franks ended acrimoniously in August 1938 he was thrown into doubt and confusion about both his homosexuality and his worth as an artist. He was saved from despair when, at Ayerst's suggestion, he undertook a course of Jungian analysis with the psychotherapist John Layard. Through an extended course of therapy, Layard gave Tippett the means to analyse and interpret his dreams. Tippett's biographer Ian Kemp describes this experience as "the major turning point in [his] life", both emotionally and artistically. His particular discovery from dream analysis was "the Jungian 'shadow' and 'light' in the single, individual psyche ... the need for the individual to accept his divided nature and profit from its conflicting demands".[42] This brought him to terms with his homosexuality, and he was able to pursue his creativity without being distracted by personal relationships.[7] While still unsure of his sexuality, Tippett had considered marriage with Francesca Allinson, who had expressed the wish that they should have children together.[42][43] After his psychotherapy he enjoyed several committed—and sometimes overlapping—same-sex relationships. Among the most enduring, and most tempestuous, was that with the artist Karl Hawker, whom he first met in 1941.[43][44]

A Child of Our Time

[edit]

While his therapy proceeded, Tippett was searching for a theme for a major work—an opera or an oratorio—that could reflect both the contemporary turmoil in the world and his own recent catharsis. Having briefly considered the theme of the Dublin Easter Rising of 1916, he based his work on a more immediate event: the murder in Paris of a German diplomat by a 17-year-old Jewish refugee, Herschel Grynszpan.[45] This murder triggered Kristallnacht (Crystal Night), a coordinated attack on Jews and their property throughout Nazi Germany on 9–10 November 1938.[42] Tippett hoped that Eliot would provide a libretto for the oratorio, and the poet showed interest. But when Tippett presented him with a more detailed scenario, Eliot advised him to write his own text, suggesting that the poetic quality of the words might otherwise dominate the music.[46] Tippett called the oratorio A Child of Our Time, taking the title from Ein Kind unserer Zeit, a contemporary protest novel by the Austro-Hungarian writer Ödön von Horváth.[47] Within a three-part structure based on Handel's Messiah, Tippett took the novel step of using North American spirituals in place of the traditional chorales that punctuate oratorio texts. According to Kenneth Gloag's commentary, the spirituals provide "moments of focus and repose ... giving shape to both the musical and literary dimensions of the work".[48] Tippett began composing the oratorio in September 1939, on the conclusion of his dream therapy and immediately after the outbreak of war.[7]

Morley, war, imprisonment

[edit]With the South London Orchestra temporarily disbanded because of the war, Tippett returned to teaching at Hazelwood. In October 1940 he accepted the post of Director of Music at Morley College, just after its buildings were almost completely destroyed by a bomb.[49] Tippett's challenge was to rebuild the musical life of the college, using temporary premises and whatever resources he could muster. He revived the Morley College Choir and orchestra, and arranged innovative concert programmes that typically mixed early music (Orlando Gibbons, Monteverdi, Dowland), with contemporary works by Stravinsky, Hindemith and Bartók.[50]

He continued the college's established association with the music of Purcell;[51] a performance in November 1941 of Purcell's Ode to St Cecilia, with improvised instruments and rearrangements of voice parts, attracted considerable attention.[52] The music staff at Morley was augmented by the recruitment of refugee musicians from Europe, including Walter Bergmann, Mátyás Seiber, and Walter Goehr, who took charge of the college orchestra.[7][53]

A Child of Our Time was finished in 1941 and put aside with no immediate prospects of performance. Tippett's Fantasia on a Theme of Handel for piano and orchestra was performed at the Wigmore Hall in March 1942, with Sellick again the soloist, and the same venue saw the première of the composer's String Quartet No. 2 a year later.[39] The first recording of Tippett's music, the Piano Sonata No. 1 played by Sellick, was issued in August 1941. The recording was well received by critics; Wilfrid Mellers predicted a leading role for Tippett in the future of English music.[54] In 1942, Schott Music began to publish Tippett's works, establishing an association that continued until the end of the composer's life.[53]

The question of Tippett's liability for war service remained unresolved until mid-1943. In November 1940 he had formalised his pacifism by joining the Peace Pledge Union and applying for registration as a conscientious objector. His case was heard by a tribunal in February 1942, when he was assigned to non-combatant duties. Tippett rejected such work as an unacceptable compromise with his principles and in June 1943, after several further hearings and statements on his behalf from distinguished musical figures, he was sentenced to three months' imprisonment in HM Prison Wormwood Scrubs. He served two months, and although thereafter he was technically liable to further charges for failing to comply with the terms set by his tribunal, the authorities left him alone.[55]

Recognition and controversy

[edit]On his release, Tippett returned to his duties at Morley, where he boosted the college's Purcell tradition by persuading the countertenor Alfred Deller to sing several Purcell odes at a concert on 21 October 1944—the first modern use of a countertenor in Purcell's music.[52] Tippett formed a fruitful musical friendship with Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, for whom he wrote the cantata Boyhood's End for tenor and piano. Encouraged by Britten, Tippett made arrangements for the first performance of A Child of Our Time, at London's Adelphi Theatre on 19 March 1944. Goehr conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and Morley's choral forces were augmented by the London Regional Civil Defence Choir.[56] Pears sang the tenor solo part, and other soloists were borrowed from Sadler's Wells Opera.[57] The work was well received by critics and the public, and eventually became one of the most frequently performed large-scale choral works of the post-Second World War period, in Britain and overseas.[58][59] Tippett's immediate reward was a commission from the BBC for a motet, The Weeping Babe,[60] which became his first broadcast work when it was aired on 24 December 1944.[61] He also began to give regular radio talks on music.[62]

In 1946 Tippett organised at Morley the first British performance of Monteverdi's Vespers, adding his own organ Preludio for the occasion.[63][64] Tippett's compositions in the immediate postwar years included his First Symphony, performed under Sargent in November 1945, and the String Quartet No. 3, premiered in October 1946 by the Zorian Quartet.[61] His main creative energies were increasingly devoted to his first major opera, The Midsummer Marriage.[62] During the six years from 1946 he composed almost no other music, apart from the Birthday Suite for Prince Charles (1948).[65]

I saw a stage picture ... of a wooded hilltop with a temple, where a warm and soft young man was being rebuffed by a cold and hard young woman ... to such a degree that the collective, magical archetypes take charge—Jung's anima and animus.

Tippett, outlining the origins of The Midsummer Marriage.[66]

The musical and philosophical ideas behind the opera had begun in Tippett's mind several years earlier.[67] The story, which he wrote himself, charts the fortunes of two contrasting couples in a manner which has brought comparison with Mozart's The Magic Flute.[68] The strain of composition, combined with his continuing responsibilities at Morley and his BBC work, affected Tippett's health and slowed progress.[69] Following the death in 1949 of Morley's principal, Eva Hubback, Tippett's personal commitment to the college waned. His now-regular BBC fees had made him less dependent on his Morley salary, and he resigned his college post in 1951. His farewell took the form of three concerts he conducted at the new Royal Festival Hall, in which the programmes included A Child of Our Time, the British première of Carl Orff's Carmina Burana, and Thomas Tallis's rarely performed 40-part motet Spem in alium.[70][71]

In 1951 Tippett moved from Limpsfield to a large, dilapidated house, Tidebrook Manor in Wadhurst, Sussex.[70] As The Midsummer Marriage neared completion he wrote a song cycle for tenor and piano, The Heart's Assurance. This work, a long-delayed tribute to Francesca Allinson (who had committed suicide in 1945), was performed by Britten and Pears at the Wigmore Hall on 7 May 1951.[43][61] The Midsummer Marriage was finished in 1952, after which Tippett arranged some of the music as a concert suite, the Ritual Dances, performed in Basel, Switzerland, in April 1953.[69] The opera itself was staged at Covent Garden on 27 January 1955. The lavish production, with costumes and stage designs by Barbara Hepworth and choreography by John Cranko, perplexed the opera-going public and divided critical opinion.[72] According to Bowen, most "were simply unprepared for a work that departed so far from the methods of Puccini and Verdi".[56][73] Tippett's libretto was variously described as "one of the worst in the 350-year history of opera"[72] and "a complex network of verbal symbolism", and the music as "intoxicating beauty" with "passages of superbly conceived orchestral writing".[74] A year after the première, the critic A.E.F. Dickinson concluded that "in spite of notable gaps in continuity and distracting infelicities of language, [there is] strong evidence that the composer has found the right music for his ends".[68]

Much of the music Tippett composed following the opera's completion reflected its lyrical style.[7] Among these was the Fantasia Concertante on a Theme of Corelli (1953) for string orchestra, written to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the composer Arcangelo Corelli's birth. The Fantasia eventually became one of Tippett's most popular works, though The Times's critic lamented the "excessive complexity of the contrapuntal writing ... there was so much going on that the perplexed ear knew not where to turn or fasten itself".[75] Such comments helped foster a view that Tippett was a "difficult" composer, or even that his music was amateurish and poorly prepared.[7] These perceptions were strengthened by controversies around several of his works in the late 1950s. The Piano Concerto (1955) was declared unplayable by its scheduled soloist, Julius Katchen, who had to be replaced before the première by Louis Kentner. The Dennis Brain Wind Ensemble, for whom Tippett had written the Sonata for Four Horns (1955), complained that the work was in too high a key and required it to be transposed down.[76] When the Second Symphony was premièred by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Boult, in a live broadcast from the Royal Festival Hall on 5 February 1958, the work broke down after a few minutes and had to be restarted by the apologetic conductor: "Entirely my mistake, ladies and gentlemen".[56][n 3] The BBC's Controller of Music defended the orchestra in The Times, writing that it "is equal to all reasonable demands", a wording that implied the fault was the composer's.[78]

International acclaim

[edit]King Priam and after

[edit]

In 1960 Tippett moved to a house in the Wiltshire village of Corsham, where he lived with his long-term partner Karl Hawker.[79] By then Tippett had begun work on his second major opera, King Priam. He chose for his theme the tragedy of Priam, mythological king of the Trojans, as recorded in Homer's Iliad, and again he prepared his own libretto.[80] As with The Midsummer Marriage, Tippett's preoccupation with the opera meant that his compositional output was limited for several years to a few minor works, including a Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis written in 1961 for the 450th anniversary of the foundation of St John's College, Cambridge.[81] King Priam was premièred in Coventry by the Covent Garden Opera on 29 May 1962 as part of a festival celebrating the consecration of the new Coventry Cathedral. The production was by Sam Wanamaker and the lighting by Sean Kenny. John Pritchard was the conductor.[82] The music for the new work displayed a marked stylistic departure from what Tippett had written hitherto, heralding what a later commentator, Iain Stannard, calls a "great divide" between the works before and after King Priam.[83] Some commentators questioned the wisdom of so radical a departure from his established voice,[84] but the opera was a considerable success with critics and the public. Lewis later called it "one of the most powerful operatic experiences in the modern theatre".[85] This reception, combined with the fresh acclaim for The Midsummer Marriage following a well-received BBC broadcast in 1963, did much to rescue Tippett's reputation and establish him as a leading figure among British composers.[86]

As with The Midsummer Marriage, the compositions that followed King Priam retained the musical idiom of the opera, notably the Piano Sonata No. 2 (1962) and the Concerto for Orchestra (1963), the latter written for the Edinburgh Festival and dedicated to Britten for his 50th birthday.[82][87] Tippett's main work in the mid-1960s was the cantata The Vision of Saint Augustine, commissioned by the BBC, which Bowen marks as a peak of Tippett's compositional career: "Not since The Midsummer Marriage had he unleashed such a torrent of musical invention".[88] His status as a national figure was now being increasingly recognised. He had been appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1959; in 1961 he was made an honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Music (HonFRCM), and in 1964 he received from Cambridge University the first of many honorary doctorates. In 1966 he was knighted.[56][89]

Wider horizons

[edit]In 1965 Tippett made the first of several visits to the United States, to serve as composer in residence at the Aspen Music Festival in Colorado. His American experiences had a significant effect on the music he composed in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with jazz and blues elements particularly evident in his third opera, The Knot Garden (1966–69), and in the Symphony No. 3 (1970–72).[7][90] At home in 1969, Tippett worked with the conductor Colin Davis to rescue the Bath International Music Festival from a financial crisis, and became the festival's artistic director for the next five seasons.[91][92] In 1970, following the collapse of his relationship with Hawker, he left Corsham and moved to a secluded house on the Marlborough Downs.[92] Among the works he wrote in this period were In Memoriam Magistri (1971), a chamber piece commissioned by Tempo magazine as a memorial to Stravinsky, who had died on 6 April 1971,[91] and the Piano Sonata No. 3 (1973).[93]

In February 1974 Tippett attended a "Michael Tippett Festival" arranged in his honour by Tufts University, near Boston, Massachusetts. He was also present at a performance of The Knot Garden at Northwestern University at Evanston, Illinois—the first Tippett opera to be performed in the US.[94] Two years later he was again in the country, engaged on a lecture tour that included the Doty Lectures in Fine Art at the University of Texas.[95] Between these American journeys, Tippett travelled to Lusaka for the first African performance of A Child of Our Time, at which the Zambian president, Kenneth Kaunda, was present.[96]

In 1976 Tippett was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society.[89] The following few years saw journeys to Java and Bali—where he was much attracted by the sounds of gamelan ensembles—and to Australia, where he conducted a performance of his Fourth Symphony in Adelaide.[97][n 4] In 1979, with funds available from the sale of some of his original manuscripts to the British Library, Tippett inaugurated the Michael Tippett Musical Foundation, which provided financial support to young musicians and music education initiatives.[99]

Tippett maintained his pacifist beliefs, while becoming generally less public in expressing them, and from 1959 served as president of the Peace Pledge Union. In 1977 he made a rare political statement when, opening a PPU exhibition at St Martin-in-the-Fields, he attacked President Carter's plans to develop a neutron bomb.[100]

Later life

[edit]In his seventies, Tippett continued to compose and travel, although now handicapped by health problems. His eyesight was deteriorating as a result of macular dystrophy, and he relied increasingly on his musical amanuensis Michael Tillett,[101] and on Meirion Bowen, who became Tippett's assistant and closest companion in the remaining years of the composer's life.[36][43] The main works of the late 1970s were a new opera, The Ice Break, the Symphony No. 4, the String Quartet No. 4, and the Triple Concerto for violin, viola and cello. The Ice Break was a reflection of Tippett's American experiences, with a contemporary storyline incorporating race riots and drug-taking. His libretto has been criticised for its awkward attempts at American street vernacular,[102] and the opera has not found a place in the general repertory. Mellers finds that its fusion of "art music, rock ritual and performance art fail to gel".[103] The Triple Concerto includes a finale inspired by the gamelan music Tippett absorbed during his visit to Java.[104]

In 1979 Tippett was made a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH).[89] The main composition that occupied him in the early 1980s was his oratorio The Mask of Time, loosely based on Jacob Bronowski's 1973 TV series The Ascent of Man.[7] In Tippett's words, this is an attempt to deal "with those fundamental matters that bear upon man, his relationship with Time, his place in the world as we know it and in the mysterious universe at large".[105] The oratorio was commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra for its centenary, and was one of several of Tippett's late compositions that were premièred in America.[106]

In 1983 Tippett became president of the London College of Music[95] and was appointed a Member of the Order of Merit (OM).[7] By the time of his 80th birthday in 1985 he was blind in his right eye, and his output had slowed.[95] Nevertheless, in his final active years he wrote his last opera, New Year. This futuristic fable involving flying saucers, time travel, and urban violence was indifferently received on its première in Houston, Texas, on 17 October 1989. Donal Henahan in The New York Times wrote, "Unlike Wagner, [Tippett] does not provide music of enough quality to allow one to overlook textual absurdities and commonplaces."[107] The opera was introduced to Britain in the Glyndebourne Festival of 1990.[108]

Despite his deteriorating health, Tippett toured Australia in 1989–90, and also visited Senegal. His last major works, written between 1988 and 1993, were Byzantium, for soprano and orchestra; the String Quartet No. 5; and The Rose Lake, a "song without words for orchestra" inspired by a visit to Lake Retba in Senegal during his 1990 trip.[7][109] He intended The Rose Lake to be his farewell, but in 1996 he broke his retirement to write "Caliban's Song" as a contribution to the Purcell tercentenary.[7]

Death

[edit]In 1997 he moved from Wiltshire to London to be closer to his friends and caregivers; in November of that year he made his last overseas trip, to Stockholm for a festival of his music.[7] After suffering a stroke he was taken home, where he died on 8 January 1998, six days after his 93rd birthday.[110] He was cremated on 15 January, at Hanworth crematorium, after a secular service.[7]

Music

[edit]General character

[edit]Bowen has called Tippett "a composer of our time", one who engaged with the social, political and cultural issues of his day.[111] Arnold Whittall sees the music as embodying Tippett's philosophy of "ultimately optimistic humanism".[112] Rather than ignoring the barbarism of the 20th century, says Kemp, Tippett chose through his works to seek "to preserve or remake those values that have been perverted, while at the same time never losing sight of the contemporary reality".[113] The key early work in this respect is A Child of Our Time, of which Clarke writes: "[t]he words of the oratorio's closing ensemble, 'I would know my shadow and my light, So shall I at last be whole', have become canonical in commentary on Tippett ... this [Jungian] statement crystallizes an ethic, and aesthetic, central to his world-view, and one which underlies all his text-based works".[36]

Sceptical critics such as the musicologist Derrick Puffett have argued that Tippett's craft as a composer was insufficient for him to deal adequately with the task that he had set himself of "transmut[ing] his personal and private agonies into ... something universal and impersonal".[114] Michael Kennedy has referred to Tippett's "open‐eyed, even naive outlook on the world", while accepting the technical sophistication of his music.[115] Others have acknowledged his creative ingenuity and willingness to adopt whatever means or techniques were necessary to fit his intentions.[7][116]

Tippett's music is marked by the expansive nature of his melodic line—the Daily Telegraph's Ivan Hewett refers to his "astonishingly long-breathed melodies".[117] According to Jones, a further element of the "individual voice" that emerged in 1935 was Tippett's handling of rhythm and counterpoint, demonstrated in the First String Quartet—Tippett's first use of the additive rhythm and cross-rhythm polyphony which became part of his musical signature.[118][119][n 5] This approach to metre and rhythm is derived in part from Bartók and Stravinsky but also from the English madrigalists.[121] Sympathy with the past, observed by Colin Mason in an early appraisal of the composer's work,[122] was at the root of the neoclassicism that is a feature of Tippett's music, at least until the Second Symphony (1957).[123][124]

In terms of tonality, Tippett shifted his ground in the course of his career. His earlier works, up to The Midsummer Marriage, are key-centred, but thereafter he moved through bitonality into what the composer Charles Fussell has called "the freely-organized harmonic worlds" of the Third Symphony and The Ice Break.[125] Although Tippett flirted with the "twelve-tone" technique—he introduced a twelve-tone theme into the "storm" prelude that begins The Knot Garden—Bowen records that he generally rejected serialism as incompatible with his musical aims.[126]

Compositional process

[edit]Tippett described himself as the receiver of inspiration rather than its originator, the creative spark coming from a particular personal experience, which might take one of many forms but was most often associated with listening to music.[127] The process of composing was lengthy and laborious, the actual writing down of the music being preceded by several stages of gestation; as Tippett put it, "the concepts come first, and then a lot of work and imaginative processes until eventually, when you're ready, finally ready, you look for the actual notes".[128] He elaborated: "I compose by first developing an overall sense of the length of the work, then of how it will divide itself into sections or movements, then of the kind of texture or instruments or voices that will be performing it. I prefer not to consider the actual notes of the composition until this process ... has gone as far as possible".[129] Sometimes the time required to see a project through from conception to completion was very long—seven years, Tippett said, in the case of the Third Symphony.[130] In the earlier, contemplative stages he might be simultaneously engaged on other works, but once these stages were complete he would dedicate himself entirely to the completion of the work in hand.[131]

Tippett preferred to compose in full score; once the writing began, progress was often not fluent, as evidenced by Tippett's first pencil draft manuscripts, which show multiple rubbings-out and reworkings. In this, the musicologist Thomas Schuttenhelm says, his methods resembled those of Beethoven, with the difference that "whereas Beethoven's struggle is considered a virtue of his work, and almost universally admired, Tippett's was the source and subject of a debate about his competency as a composer".[132]

Influences

[edit]"During his fifty or so years as a composer, Tippett has undoubtedly cultivated a distinctive language of his own. The prime emphasis in this language has been on a linear organisation of musical ideas, helped by a genuine flair for colour and texture."

Meirion Bowen, writing in 1982.[133]

The style that emerged from Tippett's long compositional apprenticeship was the product of many diverse influences. Beethoven and Handel were initial models (Handel above Bach, who in Tippett's view lacked drama), supplemented by 16th- and 17th-century masters of counterpoint and madrigal—Thomas Weelkes, Monteverdi and Dowland.[134] Purcell became significant later, and Tippett came to lament his ignorance of Purcell during his RCM years: "It seems to me incomprehensible now that his work was not even recommended in composition lessons as a basic study for the setting of English".[135][136]

Tippett recognised the importance to his compositional development of several 19th- and 20th-century composers: Berlioz for his clear melodic lines,[134] Debussy for his inventive sound, Bartók for his colourful dissonance, Hindemith for his skills at counterpoint, and Sibelius for his originality in musical forms.[137] He revered Stravinsky, sharing the Russian composer's deep interest in older music.[138] Tippett had heard early ragtime as a small child before the First World War; he noted in his later writings that, in the early years of the 20th century, ragtime and jazz "attracted many serious composers thinking to find ... a means to refresh serious music by the primitive".[139] His interest in these forms led to his fascination with blues, articulated in several of his later works.[36][140] Among his contemporary composers, Tippett admired Britten and shared his desire to end the perception of English music as provincial.[141] He also had a high regard for Alan Bush, with whom he joined forces to produce the 1934 Pageant of Labour. "I can remember the excitement I felt when he outlined to me his plan for a major string quartet".[142]

Although influences of folk music from all parts of the British Isles are evident in Tippett's early works, he was wary of the English folksong revival of the early 20th century, believing that much of the music presented as "English" by Cecil Sharp and his followers originated elsewhere.[135] Notwithstanding his doubts, Tippett took some inspiration from these sources. The composer David Matthews writes of passages in Tippett's music which "evoke the 'sweet especial rural scene' as vividly as Elgar or Vaughan Williams ... perhaps redolent of the Suffolk landscape with its gently undulating horizons, wide skies and soft lights".[143]

Works

[edit]After the withdrawn works of the 1920s and early 1930s, analysts generally divide Tippett's mature compositional career into three main phases, with fairly fluid boundaries and some internal subdivision in each. The first phase extends from the completion of the String Quartet No. 1 in 1935 to the end of the 1950s, a period in which Tippett drew on the past for his main inspiration.[36][144] The 1960s marked the beginning of a new phase in which Tippett's style became more experimental, reflecting both the social and cultural changes of that era and the broadening of his own experiences. The mid-1970s produced a further stylistic change, less marked and sudden than that of the early 1960s, after which what Clarke calls the "extremes" of the experimental phase were gradually replaced by a return to the lyricism characteristic of the first period, a trend that was particularly manifested in the final works.[36][144]

Withdrawn compositions

[edit]"I had never heard the work when I came across the Chrysander Edition [of Messiah]. It was a revelation. I was astounded by the power of the work's direct utterance. We gave a reasonably authentic performance and it taught me a tremendous amount. After that, Handel rather than Bach, became my bible. Those single lines—violin, soprano and figured bass—impressed me most."

Tippett's reaction to Handel's Messiah, after supervising a performance in 1930.[145]

Tippett's earliest compositions cover several genres. Kemp writes that the works indicate Tippett's deep commitment to learning his craft, his early ability to manipulate traditional forms, and a general willingness to experiment.[144] Clarke observes that in these youthful efforts, characteristics of his mature work are already discernible.[36] Some of the early work is of high quality—the Symphony in B flat of 1933 was, in Kemp's view, comparable to William Walton's contemporaneous First Symphony. Tippett pondered for years whether to include this work in his formal canon before deciding that its debt to Sibelius was too great. Nevertheless, it foreshadows techniques that feature in the String Quartet No. 1 and in the Corelli Fantasia.[144]

Other accomplished early works include the two string quartets, composed between 1928 and 1930, in which Tippett sought to combine the styles of Beethoven and Haydn respectively with folk-song, as Beethoven had in his Rasoumovsky quartets of 1806.[144] Tippett explains the withdrawal of these and the other early works: "I realised very clearly that they were not totally consonant with myself. I didn't think they had the stamp of artistic durability. So I took the whole lot along to R.O. Morris who agreed that they didn't show enough technical mastery."[145]

First period: 1935 to late 1950s

[edit]Kemp identifies the String Quartet No. 1 (1935) as marking Tippett's discovery of his individual voice.[146][n 6] According to the composer Alan Ridout, the work stamped its character on Tippett's first period, and together with the second and third quartets of 1942 and 1946 it typifies his style up to The Midsummer Marriage.[148] In the two works that immediately followed the first quartet, Bowen finds the Piano Sonata No. 1 (1938) full of the young composer's inventiveness,[98] while Matthews writes of the Concerto for Double String Orchestra (1939): "[I]t is the rhythmic freedom of the music, its joyful liberation from orthodox notions of stress and phrase length, that contributes so much to its vitality".[149] Both of these works show influence of folk music, and the finale of the Piano Sonata is marked by innovative jazz syncopations.[36][98] According to Schuttenhelm, the Double Concerto marks the proper beginning of Tippett's maturity as an orchestral composer.[150]

Although [Tippett] is no imitator of archaic styles, he goes back to old music to find in it what he wants for the present day ... He feels that in the musical outlook of the 16th and 17th century lies the clue to what composers in this century should do in order to restore to their music a greater measure of contact with and intelligibility to the general public.

Colin Mason in 1946, analysing Tippett's early career.[122]

In A Child of Our Time Tippett was, in Kemp's view, wholly successful in integrating the language of the spirituals with his own musical style. Tippett had obtained recordings of American singing groups, especially the Hall Johnson Choir,[151] which provided him with a model for determining the relationships between solo voices and chorus in the spirituals.[152] Thus, Kemp believes, the fourth spiritual "O by and by" sounds almost as if it had been composed by Tippett.[151] The composer's instructions in the score specify that "the spirituals should not be thought of as congregational hymns, but as integral parts of the Oratorio; nor should they be sentimentalised but sung with a strong underlying beat and slightly 'swung'".[153]

In Tippett's Symphony No. 1 (1945), his only large-scale work between A Child of Our Time and The Midsummer Marriage, his "gift for launching a confident flow of sharply characterized, contrapuntally combined ideas" is acknowledged by Whittall. The same critic found the symphony's quality uneven, and the orchestral writing weaker than in the Double Concerto.[154] Whittall offers nearly unqualified praise for The Midsummer Marriage,[65] a view largely echoed by Mellers, who saw the perceived "difficulty" of the music as "an aspect of its truth". He considered the opera one of the best musical-theatrical works of its era.[155]

Three major works of the 1950s round off Tippett's first period: the Corelli Fantasia (1953), in which Clarke sees, in the alla pastorale section, the composer's instrumental writing at its best;[36] the mildly controversial Piano Concerto (1955), which Whittall regards as one of the composer's most intriguing works—an attempt to "make the piano sing";[156] and the Symphony No. 2 (1957) which Tippett acknowledges as a turning-point in his music.[157] Until this point, says Matthews, Tippett's style had remained broadly tonal. The Second Symphony was his first essay in polytonality, paving the way to the dissonance and chromaticism of subsequent works.[158] Milner, too, recognises the pivotal position of this symphony in Tippett's development which, he says, both sums up the style of the late 1950s and presages the changes to come.[121]

Second period: King Priam to 1976

[edit]In his analysis of King Priam, Bowen argues that the change in Tippett's musical style arose initially from the nature of the opera, a tragedy radically different in tone from the warm optimism of The Midsummer Marriage.[159] Clarke sees the change as something more fundamental, the increases in dissonance and atonality in Priam being representative of a trend that continued and reached a climax of astringency a few years later in Tippett's third opera, The Knot Garden. Tippett's new modernistic language, writes Clarke, was rooted in his desire to represent a wider range of human experiences, characteristic of a changing world: "War, violence, sex, homoeroticism, and social and interpersonal alienation [would now feature] much more overtly in [his] dramatic works or works with text".[36] Critics acknowledged Priam as a considerable achievement, but received the new musical style cautiously. Gloag did not think the change an absolute departure from Tippett's earlier style,[160] but Milner viewed King Priam as a complete break with Tippett's previous work, pointing out the lack of counterpoint, the considerably increased dissonances, and the move towards atonality: "very little of the music is in a definite key".[121]

"Compared with the Concerto for Orchestra both Priam and the Piano Sonata No. 2 seem preliminary studies ... The occasional harshness of the orchestra in Priam has yielded to a new sweetness and brilliance, while the dissonances are less strident and percussive ... This Concerto triumphantly justifies Tippett's recent experiments"

Anthony Milner on the Concerto for Orchestra (1963).[121]

Many of the minor works that Tippett wrote in the wake of King Priam reflect the musical style of the opera, in some cases quoting directly from it.[161] In the first purely instrumental post-Priam work, the Piano Sonata No. 2 (1962), Milner thought the new style worked better in the theatre than in the concert or recital hall, although he found the music in the Concerto for Orchestra (1963) had matured into a form that fully justified the earlier experiments.[121] The critic Tim Souster refers to Tippett's "new, hard, sparse instrumental style" evident in The Vision of Saint Augustine (1965), written for baritone soloist, chorus and orchestra,[162] a work Bowen considers one of the peaks of Tippett's career.[88]

During the late 1960s Tippett worked on a series of compositions that reflected the influence of his American experiences after 1965: The Shires Suite (1970), The Knot Garden (1970) and the Symphony No. 3 (1972).[163] In The Knot Garden Mellers discerns Tippett's "wonderfully acute" ear only intermittently, otherwise: "thirty years on, the piece still sounds and looks knotty indeed, exhausting alike to participants and audience".[103] The Third Symphony is overtly linked by Tippett to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony through a vocal finale of four blues songs, introduced by a direct quotation from Beethoven's finale. Tippett's intention, explained by the music critic Calum MacDonald, was to explore the contemporary relevance of the grand, universal sentiments in Schiller's Ode to Joy, as set by Beethoven. Tippett's conclusion is that while the need to rejoice remains, the 20th century has put paid to the Romantic ideals of universality and certainty.[90]

After completing his Piano Sonata No. 3 (1973), "a formidable piece of abstract composition" according to Bowen,[93] Tippett returned to the modern vernacular in his fourth opera, The Ice Break (1976). Describing the music in an introduction to the published libretto, Tippett identifies "two archetypal sounds: one relating to the frightening but exhilarating sound of the ice breaking on the great northern rivers in the spring; the other related to the exciting or terrifying sound of the slogan-shouting crowds, which can lift you on your shoulders in triumph, or stamp you to death".[164] The work was generally regarded as a critical and public failure, but aspects of its music have been recognised as among Tippett's best. The critic John Warrack writes that, after the violence of the opening acts, the third act's music has a lyrical warmth comparable to that of The Midsummer Marriage".[165] William Mann in The Times was equally enthusiastic, finding the music compelling and worthy of many a rehearing.[166]

Third period: 1977 to 1995

[edit]In the late 1970s Tippett produced three single-movement instrumental works: the Symphony No. 4 (1977), the String Quartet No. 4 (1978), and the Triple Concerto for violin, viola and cello (1979). The symphony, written in the manner of the tone poem or symphonic fantasia exemplified by Sibelius,[167] represents what Tippett describes as a birth-to-death cycle, beginning and ending with the sounds of breathing.[168] This effect was initially provided by a wind machine, although other means have been tried, with mixed results—according to Bowen "the sounds emitted can turn out to be redolent of a space-fiction film or a bordello".[167] The Fourth String Quartet, Tippett explains, is an exercise in "finding a sound" that he first encountered in the incidental music to a television programme on Rembrandt.[169] In the Triple Concerto, which is thematically related to the Fourth Quartet and quotes from it,[170] the three solo instruments perform individually rather than as a formal grouping. The work acknowledges Tippett's past with quotations from The Midsummer Marriage.[171]

"If this is, perhaps, a music which claims a momentary exemption from modernist prohibitions and complex argument, it is also an intensely personal affirmation of a humanism that will not be extinguished".

David Clarke, on Tippett's late works.[36]

Tippett described the longest and most ambitious of his late works, the oratorio The Mask of Time (1982), as "a pageant of sorts with an ultimately lofty message".[172] Mellers called the work "a mind-boggling cosmic history of the universe".[173] Paul Driver, who had been a critic of Tippett's new style, wrote that the Mask revealed "the authentic early Tippett", with a return to the lyricism of The Midsummer Marriage and multiple acknowledgements of his early compositions.[174]

Tippett had intended The Ice Break to be his final opera, but in 1985 he began work on New Year. Bowen saw this work as a summary of ideas and images that had attracted Tippett throughout his working life.[175] Donal Henahan was dismissive of the music: "the score generally natters along in the numbing, not-quite-atonal but antimelodic style familiar from other Tippett works."[107] In Byzantium (1990), Tippett set the five stanzas of W. B. Yeats's poem, with added orchestral interludes. By this time he was professing little interest in his own work beyond its creation; performance and reception had become irrelevant to him. In 1996 he told an interviewer: "I'm outside the music I've made, I have no interest in it".[176][177] After the String Quartet No. 5 (1991), which connects thematically with earlier works,[178] Tippett closed his main output with The Rose Lake (1993), described in Tippett's Daily Telegraph obituary as "of luminous beauty ... a worthy ending to a remarkable career".[179]

Reputation and legacy

[edit]

In a joint study of Tippett and Britten published in 1982, Whittall designated the pair as "the two best British composers of that ... generation born between 1900 and the outbreak of the First World War, and among the best of all composers born in the first two decades of the twentieth century".[180] After Britten's death in 1976, Tippett became widely regarded as the doyen of British music,[36] but critical opinion of his later works was not always favorable. After the first performance of the Triple Concerto in 1980, Driver wrote that "not since The Knot Garden has [he] produced anything worthy of his early masterpieces".[181]

In 1982, in his comparative study of Britten and Tippett, Whittall asserted that "it would be difficult to claim that any of the works [Tippett] has begun in his seventies are the equal of earlier compositions".[182] Although both Driver and Whittall later modified their opinions,[183] such comments represented a general view among critics that Tippett's creative powers had begun to decline after the triumph of King Priam. This perception was strongly expressed by Derek Puffett, who argued that the decline followed Tippett's abandonment of myth—seen as the key to the success of The Midsummer Marriage and King Priam—and stemmed from his increasingly futile efforts to universalise his private agonies and express them musically. Despite his admiration for the early works, Puffett consigned Tippett "to the ranks of those noble but tragic composers who have lived beyond their time".[114] The critic Norman Lebrecht, writing in 2005, dismissed almost all Tippett's output, labelling him "a composer to forget". With the forthcoming centenary celebrations in mind, Lebrecht wrote: "I cannot begin to assess the damage to British music that will ensue from the coming year's purblind promotion of a composer who failed so insistently to observe the rules of his craft".[184]

Against these criticisms Kemp maintained that while the style had become less immediately accessible, Tippett's later works showed no loss of creative power.[185] The critic Peter Wright, writing in 1999, challenged the "decline" theory with the view that the later compositions are "harder to come to terms with ... because of the more challenging nature of their musical language", a theme he developed in a detailed study of the Fifth String Quartet.[186]

After Tippett's death the more popular pieces from his first period continued to be played, but there was little public enthusiasm for the later works. After the relatively muted 2005 centenary celebrations, performances and recordings tailed off.[187] In October 2012 Hewett wrote in the Daily Telegraph of a "calamitous fall" in Tippett's reputation since his death.[117] Geraint Lewis acknowledges that "no consensus yet exists in respect of the works composed from the 1960s onwards", while forecasting that Tippett will in due course be recognised as one of the most original and powerful musical voices of twentieth-century Britain".[7]

Many of Tippett's articles and broadcast talks were issued in collections between 1959 and 1995. In 1991 he published an episodic autobiography, Those Twentieth Century Blues, notable for its frank discussions of personal issues and relationships.[188] Collectively, Tippett's writings define his aesthetic standpoint, which Clarke summarises thus: "Tippett holds that art's role in post-Enlightenment culture is to offer a corrective to society's spiritually injurious domination by mass technology. Art, he suggests, can articulate areas of human experience, unapproachable through scientific rationality, by presenting 'images' of the inner world of the psyche."[36]

Although Tippett did not found a compositional school, composers who have acknowledged his influence include David Matthews and William Mathias.[189][190] More generally, his musical and educational influence continues through the Michael Tippett Foundation. He is also commemorated in the Michael Tippett Centre, a concert venue within the Newton Park campus of Bath Spa University.[191] In Lambeth, home of Morley College, is Heron Academy (previously named The Michael Tippett School), an educational facility for young people aged 11–19 with complex learning disabilities.[192] Within the school's campus is the Tippett Music Centre, which offers music education for children of all ages and levels of ability.[193]

Writings

[edit]Three collections of Tippett's articles and broadcast talks have been published:

- Moving into Aquarius (1959). London, Routledge and Kegan Paul. OCLC 3351563

- Music of the Angels: essays and sketchbooks of Michael Tippett (1980). London, Eulenburg Books. ISBN 0-903873-60-5

- Tippett on Music (1995). Oxford, Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-816541-2

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Tippett could have studied with Ralph Vaughan Williams, but decided against this because he thought that study under so distinguished a teacher would lead him to imitation rather than towards finding his own voice.[17]

- ^ In 1938, with financial help from his father, Tippett bought this cottage and some adjoining land, and built a new bungalow on the site, which remained his home until 1951.[27]

- ^ Tippett put most of the blame on the orchestra's leader, Paul Beard, "who was always very difficult about my music". Beard had reorganised the string parts, despite Tippett's warning that this would lead to trouble. According to Tippett, Beard also "slowed down his violin solo in the scherzo, and the string-playing in general became more and more ragged".[77]

- ^ Tippett had heard recordings of gamelan orchestras in his youth, and incorporated the sound briefly into the first movement of Piano Sonata No. 1 of 1938.[98]

- ^ "Additive rhythm" is defined by Nicholas Jones as "the technique whereby a regular pulse is replaced by a series of irregular rhythmic metres".[120]

- ^ Tippett revised the quartet in 1943 by merging the first two movements into one, a change about which, Whittall records, he later expressed some reservations.[147]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Kemp, pp. 1–3

- ^ Bowen, p. 15

- ^ Kemp, pp. 4–5

- ^ Kemp, pp. 6–8

- ^ Tippett (1991), p. 5

- ^ Tippett (1991) p. 7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Lewis (2004)

- ^ Bowen, p. 16

- ^ a b Kemp, pp. 9–10

- ^ Tippett (1991), pp. 8–9

- ^ Armstrong, Thomas; et al. (6 January 2011). "Sargent, Sir (Harold) Malcolm Watts". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35949. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ^ Kemp, pp. 6–7

- ^ Kemp, p. 11

- ^ a b c Kemp, p. 12

- ^ Tippett (1991), p. 11

- ^ Bowen, p. 17

- ^ a b c d Bowen, p. 18

- ^ Tippett (1991), pp. 17–18

- ^ Kemp, pp. 14–15

- ^ Tippett (1991), pp. 14–15

- ^ a b c Kemp, pp. 16–17

- ^ a b Cole, pp. 49–50

- ^ a b c Kemp, pp. 18–22

- ^ Tippett (1991), p. 22

- ^ Bowen, pp. 19–20

- ^ Tippett (1991), p. 23

- ^ Kemp, pp. 17–18

- ^ a b Kemp, p. 33

- ^ Bowen, pp. 21–22

- ^ Tippett (1991), pp. 57–58

- ^ a b Kemp, pp. 30–32

- ^ a b Kemp, pp. 25–28

- ^ a b Tippett (1991), p. 42

- ^ Cole, p. 60

- ^ Kemp, pp. 296–298

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Clarke, David. "Tippett, Sir Michael (Kemp)". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 26 August 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ Plant, J.J. (1998). "Michael Tippett (1905–1998)". Revolutionary History. 7 (1). Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Rees, p. xxiv

- ^ a b c Kemp, pp. 498–499

- ^ Schuttenhelm, Thomas (2005). Selected Letters of Michael Tippett. Faber and Faber. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-571-22600-9.

- ^ Gilgan, Danyel. "Michael Tippett: love in the age of extremes". The British Library. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Kemp, pp. 36–37

- ^ a b c d Robinson, pp. 96–98

- ^ Tippett (1991), pp. 231–232

- ^ Whittall (1982), p. 71

- ^ Tippett (1991), pp. 50–51

- ^ Steinberg, pp. 284–285

- ^ Gloag, A Child of Our Time, pp. 27–30

- ^ Tippett (1991), p. 113

- ^ Kemp, pp. 40, 45–46

- ^ Mark, pp. 37–38

- ^ a b Kemp, pp. 44–45

- ^ a b Bowen, pp. 24–25

- ^ Kemp, p. 51

- ^ Kemp, pp. 41–43

- ^ a b c d Kemp, pp. 52–55

- ^ Gloag, A Child of Our Time, p. 89

- ^ Steinberg, p. 287

- ^ Bowen, p. 35

- ^ Rees, p. xxvi

- ^ a b c Kemp, pp. 500–501

- ^ a b Bowen, p. 26

- ^ Cole, p. 59

- ^ Kemp, p. 181

- ^ a b Whittall (1982), p. 141

- ^ Tippett (1959), pp. 54–55

- ^ Gloag, "Tippett's Operatic World", p. 231

- ^ a b Dickinson, Alan Edgar Frederic (January 1956). "Round about The Midsummer Marriage". Music & Letters. 37 (1): 50–60. doi:10.1093/ml/37.1.50. JSTOR 729998. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Bowen, p. 27

- ^ a b Kemp, pp. 47–48

- ^ Tippett (1991), pp. 158–159

- ^ a b Gloag, "Tippett's Operatic World", pp. 230–231

- ^ Bowen, p. 28

- ^ Heyworth, Peter (30 January 1955). "The Midsummer Marriage". The Observer. London. p. 11.

- ^ The Times, 4 September 1953, quoted in Kemp, p. 52

- ^ Bowen, p. 30

- ^ Tippett (1991), pp. 207–209

- ^ Letter from R.J.F. Howgill to The Times, quoted in Kemp, p. 54

- ^ Tippett (1991), pp. 230–231

- ^ Gloag, "Tippett's Operatic World", p. 240

- ^ Kemp, pp. 373–374

- ^ a b Kemp, pp. 502–503

- ^ Stannard, p. 121

- ^ Kemp, p. 322

- ^ Sadie and Macy (eds), pp. 329–332

- ^ Bowen, p. 31

- ^ Bowen, p. 33

- ^ a b Bowen, p. 144

- ^ a b c Bowen, p. 32

- ^ a b MacDonald, Calum (1972). "Tippett's Third Symphony". Tempo (102): 25–27. doi:10.1017/S0040298200056680. JSTOR 942845. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Rees, p. xxix

- ^ a b Bowen, p. 37

- ^ a b Bowen, p. 122

- ^ Kemp, p. 57

- ^ a b c Rees, p. xxx

- ^ Tippett (1991), p. 244

- ^ Kemp, p. 58

- ^ a b c Bowen, p. 93

- ^ "The Michael Tippett Musical Foundation: History". The Michael Tippett Musical Foundation. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ Kemp, p. 49

- ^ Tippett (1991), p. 116

- ^ Kemp, p. 462

- ^ a b Mellers, pp. 195–196

- ^ Bowen, pp. 131–132

- ^ Tippett: Introduction, The Mask of Time, quoted in Clarke, David. "Tippett, Sir Michael (Kemp)". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 26 August 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ Kemp, pp. 504–505

- ^ a b Henahan, Donal (30 October 1989). "Time Traveling and Agoraphobia in Tippett Opera". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ "First Performances: Tippett's New Year". Tempo. New Series. 3 (175): 35–38. December 1990. ISSN 1478-2286. (subscription required)

- ^ Schuttenhelm (2013), p. 109

- ^ Driver, Paul; Revill, David (10 January 1998). "Obituary: Sir Michael Tippett". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Bowen, Meirion (1 July 2013). "A Composer of Our Time: How Sir Michael Tippett's Activism Could Be an Inspiring Example in Our Modern World". Huffington Post Blog. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ Whittall, Arnold; Griffiths, Paul (January 2011). Tippett, Sir Michael (Kemp). Oxford Companion to Music Online. ISBN 978-0-19-957903-7. Retrieved 1 October 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ Kemp, pp. 481–482

- ^ a b Puffett, Derrick (January 1995). "Tippett and the Retreat from Mythology". The Musical Times. 136 (1823): 6–14. doi:10.2307/1003276. JSTOR 1003276.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (21 May 2013). "Tippett, Michael". Oxford Dictionary of Music Online. ISBN 978-0-19-957810-8. Retrieved 1 October 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ Bowen, p. 154

- ^ a b Hewett, Ivan (19 October 2012). "Michael Tippett: a visionary in the shadow of his rival". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Jones, pp. 207–208

- ^ Tippett, quoted from liner notes in Jones, p. 208

- ^ Jones, p. 208

- ^ a b c d e Milner, Anthony (October 1964). "The Music of Michael Tippett". The Musical Quarterly. 50 (4): 423–438. doi:10.1093/mq/l.4.423. JSTOR 740954.

- ^ a b Mason, Colin (May 1946). "Michael Tippett". The Musical Times. 87 (1239): 137–141. doi:10.2307/933950. JSTOR 933950. (subscription required)

- ^ Whittall (2013), p. 13

- ^ Gloag, "Tippett's Second Symphony", pp. 78–94

- ^ Fussell, Charles (Summer 1984). "Book review: Arnold Whittall: The Music of Britten and Tippett". The Musical Quarterly. 70 (3): 413–416. doi:10.1093/mq/lxx.3.413. JSTOR 742046.

- ^ Bowen, Meiron (September 1986). Britten, Tippett and the Second English Music Renaissance. London Sinfonietta Britten–Tippett Festival 1986 (Programme Note). Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Schuttenhelm (1913), pp. 108–109

- ^ Tippett, quoted in Schuttenhelm (2013), p. 113

- ^ Tippett (1981), p. 348

- ^ Schuttenhelm (2013), p. 113

- ^ Schuttenhelm 2014, p. 14

- ^ Schuttenhelm (2014), pp. 15–16

- ^ Bowen, p. 152

- ^ a b Kemp, pp. 65–67

- ^ a b Kemp, pp. 68–69

- ^ Tippett and Bowen, p. 57

- ^ Kemp, p. 72

- ^ Bowen, p. 90

- ^ Tippett and Bowen, p. 29

- ^ Tippett and Bowen, p. 96

- ^ Kemp, p. 87

- ^ Tippett (1991), pp. 43–44

- ^ Matthews, pp. 17–18

- ^ a b c d e Kemp, pp. 73–84

- ^ a b "Alan Blyth talks to Sir Michael Tippett". Gramophone. April 1971. Retrieved 16 June 2016. Republished by Gramophone online, 29 October 2012

- ^ Kemp, p. 85

- ^ Whittall (1982), p. 32

- ^ Ridout, p. 181

- ^ Matthews, p. 27

- ^ Schuttenhelm (2014), p. 35

- ^ a b Kemp, p. 164

- ^ Kemp, p. 172

- ^ Tippett (1944), pp. ii–iv

- ^ Whittall (1982), p. 84

- ^ Mellers, p. 190

- ^ Whittall (1982), p. 155

- ^ Tippett and Bowen, p. 93

- ^ Matthews, p. 103

- ^ Bowen, p. 63

- ^ Gloag, "Tippett's Operatic World", p. 242

- ^ Kemp, p. 370

- ^ Souster, Tim (January 1966). "Michael Tippett's Vision". The Musical Times. 107 (1475): 20–22. doi:10.2307/953675. JSTOR 953675. (subscription required)

- ^ Bowen, p. 34

- ^ Tippett, Michael (May 1978). ""Back to Methuselah" and "The Ice Break"". The Shaw Review. 21 (2). Penn State University Press: 100–103. JSTOR 40682521. (subscription required)

- ^ Warrack, John (July 1977). "The Ice Break". The Musical Times. 118 (1613): 553–556. doi:10.2307/958095. JSTOR 958095. (subscription required)

- ^ William Mann, The Times 8 July 1977, quoted in Tippett, Michael (May 1978). ""Back to Methuselah" and "The Ice Break"". The Shaw Review. 21 (2). Penn State University Press: 100–103. JSTOR 40682521. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Bowen, pp. 124–125

- ^ Collisson, pp. 144–145

- ^ Tippett, quoted in Jones, p. 220

- ^ Collisson, p. 159

- ^ Gloag, "Tippett and the Concerto", pp. 186–188

- ^ Tippett and Bowen, p. 246

- ^ Mellers, p. 199

- ^ Driver, Paul (June 1984). "First Performances: "The Mask of Time"". Tempo. New Series. 149: 39–44. JSTOR 945085. (subscription required)

- ^ Bowen, quoted in Gloag, "Tippett's operatic world", p. 260

- ^ Schuttenhelm, p. 116

- ^ Tippett and Bowen, p. 106

- ^ Jones, p. 222

- ^ "Obituary: Sir Michael Tippett, OM". The Daily Telegraph. 10 January 1998. Archived from the original on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Whittall (1982), p. 2

- ^ Driver, Paul (December 1980). "Tippett's Triple Concerto". Tempo (135): 6.

- ^ Whittall (1982), p. 292

- ^ Wright, p. 221

- ^ Lebrecht, Norman (22 December 2004). "Michael Tippett—A composer to forget". La Scena Musicale online. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ^ Kemp, pp. 477–478

- ^ Wright, p. 220

- ^ Whittall (2013), p. 3

- ^ Clarke, David (August 1993). "Tippett in and out of 'Those Twentieth Century Blues': The Context and Significance of an Autobiography". Music & Letters. 74 (3): 399–491. doi:10.1093/ml/74.3.399. JSTOR 736284. (subscription required)

- ^ Dunnett, Roderick. "Matthews, David John". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ Lewis, Geraint (2001). "Mathias, William (James)". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.18063. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription required)

- ^ "Michael Tippett Centre". The Michael Tippett Centre. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ "The Michael Tippett School". Borough of Lambeth. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ "Tippett Music centre". Borough of Lambeth. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Bowen, Meirion (1983). Michael Tippett. London: Robson Books. ISBN 1-86105-099-2.

- Cole, Suzanne (2013). "Things that really interest ME: Tippett and Early Music". In Gloag, Kenneth; Jones, Nicholas (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Michael Tippett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 48–67. ISBN 978-1-107-60613-5.

- Collisson, Stephen (1999). "Significant gestures to the past: formal processes and visionary moments in Tippett's triple concerto". In Clarke, David (ed.). Tippett Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 145–65. ISBN 0-521-02683-0.

- Gloag, Kenneth (1999). "Tippett's Second Symphony, Stravinsky and the language of neoclassicism". In Clarke, David (ed.). Tippett Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–94. ISBN 0-521-02683-0.

- Gloag, Kenneth (1999). Tippett, A Child of Our Time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59753-1.

- Gloag, Kenneth (2013). "Tippett and the concerto: from Double to Triple". In Gloag, Kenneth; Jones, Nicholas (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Michael Tippett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 168–89. ISBN 978-1-107-60613-5.

- Gloag, Kenneth (2013). "Tippett's operatic world: from The Midsummer Marriage to New Year". In Gloag, Kenneth; Jones, Nicholas (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Michael Tippett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 229–263. ISBN 978-1-107-60613-5.

- Jones, Nicholas (2013). "Formal archetypes, revered masters and singing nightingales: Tippett's string quartets". In Gloag, Kenneth; Jones, Nicholas (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Michael Tippett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 206–28. ISBN 978-1-107-60613-5.

- Kemp, Ian (1987). Tippett: the Composer and his Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282017-6.

- Lewis, Geraint (23 September 2004). "Tippett, Sir Michael Kemp". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/69100. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- Mark, Christopher (2013). "Tippett and the English traditions". In Gloag, Kenneth; Jones, Nicholas (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Michael Tippett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 25–47. ISBN 978-1-107-60613-5.

- Matthews, David (1980). Michael Tippett – An Introductory Study. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-10954-3.

- Mellers, Wilfrid (1999). "Tippett at the millennium: a personal memoir". In Clarke, David (ed.). Tippett Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 186–199. ISBN 0-521-02683-0.

- Rees, Jonathan (2013). "Chronology of Tippett's life and career". In Gloag, Kenneth; Jones, Nicholas (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Michael Tippett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. xxi–xxxi. ISBN 978-1-107-60613-5.

- Ridout, Alan (1965). "The String Quartets". In Kemp, Ian (ed.). Michael Tippett: A Symposium on his 60th Birthday. Faber & Faber. OCLC 906471.

- Robinson, Suzanne (2013). "Coming out to oneself: encodings of homosexual identity from the First String Quartet to The Heart's Assurance". In Gloag, Kenneth; Jones, Nicholas (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Michael Tippett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–102. ISBN 978-1-107-60613-5.

- Sadie, Stanley; Macy, Laura, eds. (2006). The Grove Book of Operas (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530907-2.

- Schuttenhelm, Thomas (2014). The Orchestral Music of Michael Tippett: Creative Development and the Compositional Process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00024-7.

- Schuttenhelm, Thomas (2013). "Tippett's 'Between image and the imagination: Tippett's creative process'". In Gloag, Kenneth; Jones, Nicholas (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Michael Tippett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 103–18. ISBN 978-1-107-60613-5.

- Stannard, Iain (2013). "Tippett's 'great divide': before and after King Priam". In Gloag, Kenneth; Jones, Nicholas (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Michael Tippett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 121–43. ISBN 978-1-107-60613-5.

- Steinberg, Michael (2005). Choral Masterworks: a Listener's Guide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512644-0.

- Tippett, Michael (1944). A Child of Our Time: Oratorio for soli, chorus and orchestra. London: Schott & Co. Ltd. OCLC 22331371.

- Tippett, Michael (1959). Moving into Aquarius. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. OCLC 3351563.

- Tippett, Michael (1981). "The Composer's World". In Spence, Keith; Swayne, Giles (eds.). How Music Works. London: Collier Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-026-12870-4.

- Tippett, Michael (1991). Those Twentieth Century Blues. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-175307-4.

- Tippett, Michael (1995). Bowen, Meirion (ed.). Tippett on Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816542-0.

- Whittall, Arnold (1982). The Music of Britten and Tippett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23523-5.

- Whittall, Arnold (2013). "Tippett and twentieth-century polarities". In Gloag, Kenneth; Jones, Nicholas (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Michael Tippett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–24. ISBN 978-1-107-60613-5.

- Wright, Peter (1999). "Decline or renewal in late Tippett? The Fifth String Quartet in perspective". In Clarke, David (ed.). Tippett Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 200–222. ISBN 0-521-02683-0.

External links

[edit]- "Discovering Michael Tippett". BBC Radio 3.

- Tippett discography at Discogs

- Michael Tippett biography on CDMC

- 1905 births

- 1998 deaths

- 20th-century classical composers

- 20th-century British conductors (music)

- 20th-century English musicians