The Big Country

| The Big Country | |

|---|---|

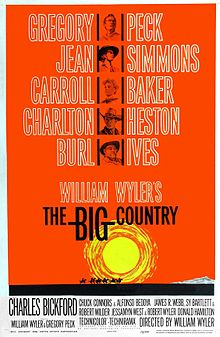

Theatrical release poster by Saul Bass | |

| Directed by | William Wyler |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by |

|

| Based on | Ambush at Blanco Canyon by Donald Hamilton |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Franz F. Planer, ASC |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Jerome Moross |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 166 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Box office | $3.5 million (US and Canada rentals)[2] |

The Big Country is a 1958 American epic Western film directed by William Wyler, starring Gregory Peck, Jean Simmons, Carroll Baker, Charlton Heston, and Burl Ives. The supporting cast features Charles Bickford and Chuck Connors. Filmed in Technicolor and Technirama, the picture was based on the serialized magazine novel Ambush at Blanco Canyon by Donald Hamilton[3] and was co-produced by Wyler and Peck. The opening title sequence was created by Saul Bass.

Burl Ives won the Academy Award as Best Supporting Actor for his performance, as well as the Golden Globe Award. The film was also nominated for an Academy Award for the musical score, composed by Jerome Moross. The film is one of the few in which Heston plays a major supporting role rather than the lead.

Plot

[edit]Former sea captain James McKay travels to the American West to join his fiancée Patricia at the enormous ranch owned by her father, Henry "The Major" Terrill. After a meeting with Patricia's friend, schoolteacher Julie Maragon, McKay, and Patricia are accosted by a group of drunks led by Buck Hannassey, the son of the Major's ardent and implacable enemy Rufus Hannassey − with whom he's had a longstanding feud over water access for cattle. In spite of the harassment and mockery, McKay surprises Patricia by making light of the incident and stating that he's experienced worse and the boys meant no harm, they were just drunk.

The next morning, McKay declines an invitation from the Major's foreman Steve Leech to ride an indomitable bronco stallion named "Old Thunder". McKay then brings a pair of dueling pistols once owned by his father to the Major as a gift. When the Major learns of Buck's pestering of his daughter and future son-in-law, he gathers his men and goes to raid the Hannassey ranch, despite McKay's attempts to defuse the situation. The Major's group of twenty men finds neither Rufus nor Buck, so they settle for terrorizing the Hannassey women and children, shooting holes in the Hannassey water reservoir. They find Buck's posse in town and proceed to beat and humiliate three of them. Meanwhile, McKay privately tames and rides Old Thunder after many unsuccessful attempts and swears his only witness, the ranch hand Ramon, to secrecy.

A gala is held on the Terrill ranch in honor of Patricia's upcoming wedding. At the height of the festivities, an armed Rufus crashes the party and accuses the Major of the hypocrisy of pretending to be a gentleman when his actions speak otherwise. The next day, McKay secretly goes to Maragon's abandoned ranch, known as the "Big Muddy", the property at the center of the Terrill-Hannassey dispute. With the only river nearby running through it, access is vital for both herds during times of drought. McKay persuades Maragon to sell the ranch to him in the hopes of both securing a gift for Patricia and ending the conflict by continuing Maragon's policy of unrestricted access to the river. McKay shows up at the camp of the Terrill search party led by Leech sent out to find the presumed lost McKay.

Upon returning to Ladder Ranch, Leech calls McKay a liar when McKay explains he was never lost or in danger. Again McKay refuses to be goaded into a fight, which disappoints Patricia enough to make the pair reconsider their engagement. Before dawn and without an audience, McKay challenges Leech to a prolonged outdoor fistfight, which ends in a draw. In the morning, Maragon tells Patricia of McKay's purchase of the Big Muddy as a wedding gift for her, which initially convinces her to attempt to make amends with McKay. When she learns of McKay's plan to allow the Hannasseys equal access to the water, she leaves for good.

Wanting to lure the Major into an ambush in the canyon leading to his homestead, Rufus takes Maragon hostage. Although McKay personally promises Rufus equal access to the water, he finds himself in a clash with Buck, which is ultimately settled with a shootout using the old dueling pistols. Buck fires before the signal, his bullet grazing McKay's forehead − and leaving him open to be shot by McKay. Buck crawls under a wagon in a display of cowardice that convinces McKay to spare him. The frustrated Buck snatches another gun from a nearby cowboy, forcing Rufus to kill his own son. Rufus then goes to the canyon for a final confrontation with the Major and challenges him to a one-on-one showdown. Armed with rifles, the two old men advance and kill one another.

With that, the hostilities end, and McKay and Julie, clearly falling in love, ride off together with Ramon to start a new life together.

Cast

[edit]- Gregory Peck as James McKay

- Jean Simmons as Julie Maragon

- Carroll Baker as Patricia Terrill

- Charlton Heston as Steve Leech

- Burl Ives as Rufus Hannassey

- Charles Bickford as Maj. Henry Terrill

- Alfonso Bedoya as Ramón Gutierrez

- Chuck Connors as Buck Hannassey

- Chuck Hayward as Rafe Hannassey

- Buff Brady as Dude Hannassey

- Jim Burk as Blackie / Cracker Hannassey

- Dorothy Adams as Hannassey Woman

- Chuck Roberson as Terrill Cowboy

Production

[edit]Robert Wyler and Jessamyn West wrote the first screenplay for the film based on the Donald Hamilton story that had been serialized in The Saturday Evening Post. Leon Uris wrote a second screenplay and Robert Wilder wrote another, with the final script by James R. Webb and Sy Bartlett. After arbitration, Webb, Bartlett and Wilder received screenplay credit and Wyler and West received adaptation credit. Uris was not given credit as his script deviated too much from the original story.[4]

Director William Wyler was known for shooting an exorbitant number of takes on his films, usually without explaining to the actors what to do differently except "[make it] better", and this one was no exception. Many of the actors, including Jean Simmons and Carroll Baker, were so traumatized by his directing style that they refused to speak about the experience for years. Simmons later said they constantly received rewrites for the script, making acting extremely difficult. Gregory Peck and Wyler, who were good friends, fought constantly on the set and had a falling out for three years, although they later reconciled. Wyler and Charles Bickford also clashed, as they had done 30 years previously on the production of his 1929 film Hell's Heroes. Burl Ives, however, claimed to have enjoyed making the film.

Before principal photography was complete, Wyler left for Rome to start work on Ben-Hur, delegating creation of the final scenes involving McKay and Maragon to his assistant Robert Swink, whose resulting scenes pleased Wyler so much that he wrote Swink a letter stating: "I can't begin to tell you how pleased I am with the new ending.... The shots you made are complete perfection."[5]

Locations

[edit]The Blanco Canyon scenes were filmed in California's Red Rock Canyon State Park in the Mojave Desert. The ranch and field scenes with greenery were filmed in the Sierra Nevada foothills near the town of Farmington in central California.[6] Today Snow Ranch, a working cattle ranch, is also used during the winter months (of lower fire risk) by a club of the National Association of Rocketry for launches of model and mid- and high-power amateur rockets.[6]

Reception

[edit]Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote in a negative review, "for all this film's mighty pretensions, it does not get far beneath the skin of its conventional Western situation and its stock Western characters. It skims across standard complications and ends on a platitude. Peace is a pious precept, but fightin' is more excitin'. That's what it proves."[7] Variety called the film "one of the best photography jobs of the year", with a "serviceable, adult" storyline "which should find favor with audiences of all tastes."[8] Harrison's Reports declared it "a first-rate super-Western, beautifully photographed in the Technirama anamorphic process and Technicolor. It is a long picture, perhaps too long for what the story has to offer, but there is never a dull moment from start to finish and it holds one's interest tightly throughout."[9] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post called it "super stuff. Franz Planer's photography of Texas is downright awe-inspiring, the characters are solid, the story line firm, the playing first-rate, the music more than dashing in this nearly three-hour tale which should delight everybody."[10]

John McCarten of The New Yorker wrote, "Of those involved in this massive enterprise, Mr. Bickford and Mr. Ives are the most commendable as they whoop and snort about the sagebrush. But even they are hardly credible types, and as for the rest of the cast, they can be set down as a rather wooden lot."[11] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times called the film "too self consciously 'epical' to be called great, but at its best, which is frequently, it's better than good."[12] The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote that the picture's attempts to convey a message were for the most part "superficial and pedestrian," and found that "the pivotal character of McKay, played on a monotonously self-righteous note by Gregory Peck, never comes alive. It is mainly due to the power of the climactic canyon battle, and Burl Ives' interesting playing as Rufus, that this remains a not unsympathetic film, decorated pleasantly by Jean Simmons and with spirit by Carroll Baker."[13]

The film was a big hit, being the second-most popular movie in Britain in 1959.[14] On review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 100% based on 13 reviews, with an average rating of 7.4/10.[15]

President Dwight D. Eisenhower liked the movie so much, he screened it on four successive evenings in the White House during his second administration.[16]

Playmobil designed an entire cowboy line based on the architecture of the film.[citation needed]

In a poll of 500 films held by Empire, it was voted 187th-greatest movie of all time.[17]

Accolades

[edit]Ives won the Academy Award as Best Supporting Actor, as well as a Golden Globe Award. The film was also nominated for an Academy Award for the musical score by Jerome Moross.[18]

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Burl Ives | Won |

| Best Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture | Jerome Moross | Nominated | |

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Film from any Source | Nominated | |

| Directors Guild of America Awards | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | William Wyler | Nominated |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Burl Ives | Won |

| Kinema Junpo Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | William Wyler | Won |

| Laurel Awards | Top Action Drama | Nominated | |

| Top Score | Jerome Moross | Nominated | |

Preservation

[edit]The Academy Film Archive preserved The Big Country in 2006.[19]

Comic book

[edit]A comic-book adaptation of the novel and tie-in to the movie was first released in 1957.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Four Eastern Openings For 'Big' This Week". Motion Picture Daily: 2. August 13, 1958.

- ^ Cohn, Lawrence (October 15, 1990). "All-Time Film Rental Champs". Variety. p. M146.

- ^ "Detail view of Movies Page". Afi.com. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "New York Soundtrack". Variety. March 26, 1958. p. 7. Retrieved October 10, 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Miller, Gabriel (2013). William Wyler: The Life and Films of Hollywood's Most Celebrated Director. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. p. 357. ISBN 978-0813142098. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ a b "Orvis Cattle Company page about the film locations".

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (October 2, 1958). "War and Peace on Range in 'Big Country'". The New York Times: 44.

- ^ "The Big Country". Variety. August 13, 1958. p. 6.

- ^ "'The Big Country' with Gregory Peck, Jean Simmons, Carroll Baker and Charlton Heston". Harrison's Reports: 128. August 9, 1958.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (August 22, 1958). "'Big Country' Is a Whopper". The Washington Post. p. B10.

- ^ McCarten, John (October 11, 1958). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 93.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (August 10, 1958). "Lengthy 'Big Country' Jogs, Lopes and Gallops". Los Angeles Times: E1.

- ^ "The Big Country". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 26 (301): 14. February 1959.

- ^ FOUR BRITISH FILMS IN 'TOP 6': BOULTING COMEDY HEADS BOX OFFICE LIST Our own Reporter. The Guardian (1959-2003) [London (UK)] 11 Dec 1959: 4.

- ^ "The Big Country". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ^ Coyne, Michael (1997). The Crowded Prairie: American National Identity in the Hollywood Western. New York, NY: I. B. Tauris. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-86064-259-3.

- ^ "Empire Features". Empireonline.com. December 5, 2006. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "Jerome Moross: The Big Country". Classic FM. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive.

External links

[edit]- 1958 films

- 1958 Western (genre) films

- 1950s American films

- 1950s English-language films

- American Western (genre) epic films

- Films adapted into comics

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on Western (genre) novels

- Films directed by William Wyler

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award-winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films about feuds

- Films scored by Jerome Moross

- Films set in the American frontier

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in the Mojave Desert

- Films with screenplays by James R. Webb

- United Artists films

- Films produced by Gregory Peck

- English-language Western (genre) films