Anthemius

| Anthemius | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Roman emperor | |||||

| Reign | 12 April 467 – 11 July 472 | ||||

| Predecessor | Libius Severus | ||||

| Successor | Anicius Olybrius | ||||

| Eastern emperor | Leo I | ||||

| Born | Constantinople[1] | ||||

| Died | 11 July 472 Rome | ||||

| Spouse | Marcia Euphemia | ||||

| Issue | Alypia Anthemiolus Marcian Romulus | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Theodosian (by marriage) | ||||

| Religion | Chalcedonian Christianity[a] | ||||

Procopius Anthemius[2] (died 11 July 472) was the Western Roman emperor from 467 to 472. Born in the Eastern Roman Empire, Anthemius quickly worked his way up the ranks. He married into the Theodosian dynasty through Marcia Euphemia, daughter of Eastern emperor Marcian. He soon received a significant number of promotions to various posts, and was presumed to be Marcian's planned successor. However, Marcian's sudden death in 457, together with that of Western emperor Avitus, left the imperial succession in the hands of Aspar, who instead appointed Leo, a low-ranking officer, to the Eastern throne, probably out of fear that Anthemius would be too independent. Eventually, this same Leo designated Anthemius as Western emperor in 467, following a two-year interregnum that started in November 465.

Anthemius attempted to solve the two primary military challenges facing the remains of the Western Roman Empire: the resurgent Visigoths, under Euric, whose domain straddled the Pyrenees; and the unvanquished Vandals, under Geiseric, in undisputed control of North Africa. Anthemius quickly began to butt heads with Ricimer, his own general of Gothic descent, who had long been the real power behind the Western throne and had controlled most previous emperors like marionettes. Unlike most of his predecessors, Anthemius refused to yield, and his insistence on ruling independently brought him into conflict with Ricimer. This eventually escalated into open warfare between the two, with the result that Anthemius lost not only his throne, but also his head, in 472.

Early life

[edit]Anthemius belonged to a noble family, the Procopii, which gave several high officers, both civil and military, to the Eastern Roman Empire. His maternal grandfather was Anthemius, praetorian prefect of the East (404–415) and Roman consul in 405. His father was Procopius, magister militum per Orientem from 422 to 424, who descended from Procopius, a cousin of Emperor Julian and a usurper against the Eastern emperor Valens (r. 365–366).[3]

Born in Constantinople, he went to Alexandria to study in the school of the Neoplatonic philosopher Proclus; among his fellow students, there were Marcellinus (magister militum and governor of Illyricum), Flavius Illustrius Pusaeus (Praetorian prefect of the East and Consul in 467), Messius Phoebus Severus (Consul in 470 and praefectus urbi), and Pamprepius (pagan poet).[4]

In 453, he married Marcia Euphemia, daughter of the Eastern emperor Marcian (450–457); after the marriage, he was elevated to the rank of comes and sent to the Danubian frontier with the task of rebuilding the border defences, neglected after Attila's death in 453. In 454, he was recalled to Constantinople, where he received the title of patricius in 454 or 455 and became one of the two magistri militum or magister utriusque militiae of the East. In 455, he received the honour of holding the consulate with the Western emperor Valentinian III as a colleague.

This succession of honourable events – the wedding with Marcian's daughter; a promotion to an important military rank, but with administrative rather than military tasks; the prestigious rank of patricius and the highest military position; the consulate held with an Emperor as a colleague – suggests that Marcian had selected Anthemius as a possible candidate for the Eastern or Western throne. This hypothesis is strengthened by Anthemius' prestige misled the 6th-century historian John Malalas to state that Marcian had designated Anthemius as Western Emperor after Avitus.[5]

In October 456, the Western emperor Avitus was deposed; Marcian probably considered Anthemius as his successor, but the Eastern emperor died in January 457 before choosing his colleague. Therefore, both empires had no emperor, and the power was in the hands of the Western generals, Ricimer and Majorian, and the Eastern Magister militum, the Alan Aspar. As Aspar could not sit on the throne because of his barbarian origin, he opposed Anthemius, whose prestige would have made him independent, and chose a low-ranking military officer, Leo; in the West, as his barbarian origin barred Ricimer from the throne, it was Majorian who received the purple.[6]

Anthemius stayed in service under the new emperor; as magister militum, his task was to defend the Empire from the barbarian populations pressing on its border. Around 460, he defeated the Ostrogoths of Valamir in Illyricum. During the winter of 466/467, he defeated a group of Huns, led by Hormidac, who had crossed the frozen Danube and pillaged Dacia. The raiders had conquered Serdica, and Anthemius besieged the city until the starved Huns decided to accept open battle; despite the treachery of his cavalry commander (a Hun), Anthemius led his infantry to victory, and when Hormidac offered surrender Anthemius asked for the deserter to be given to him.[7]

Rise to the throne

[edit]The newly elected Eastern Roman emperor, Leo I the Thracian, had a major foreign affairs problem: the Vandals of King Geiseric and their raids on the Italian coasts. After the death of Libius Severus in 465, the Western Empire had no Emperor. Gaiseric had his own candidate, Olybrius, who was related to Gaiseric because both Olybrius and a son of Gaiseric's had married the two daughters of emperor Valentinian III.

With Olybrius on the throne, Gaiseric would become the real power behind the throne of the Western Empire. Leo, on the other hand, wanted to keep Gaiseric as far as possible from the imperial court at Ravenna, and took time to choose a successor to Severus. To put Leo under pressure, Gaiseric extended his attacks on Sicily and Italy to the territories of the Eastern Empire, sacking and enslaving people living in Illyricum, the Peloponnese and other parts of Greece, so Leo was obliged to take action.

In 467, Leo I designated Anthemius as Western emperor and sent him to Italy with an army led by the Magister militum per Illyricum Marcellinus. On 12 April, Anthemius was proclaimed Emperor (augustus) at the third or twelfth mile from Rome.[8] Anthemius' election was celebrated in Constantinople with a panegyric by Dioscorus.[9]

By choosing Anthemius, Leo obtained three results: he sent a possible candidate to the Eastern throne far away; he repulsed Gaiseric's attempt to put a puppet of his own on the Western throne; and he put a capable and proven general with a trained army in Italy, ready to fight the Vandals.

Rule

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2014) |

Foreign affairs

[edit]Relationship with the Eastern Empire

[edit]The reign of Anthemius was characterised by a good diplomatic relationship with the Eastern Empire; for example, Anthemius is the last Western Emperor to be recorded in an Eastern law.[10] Both courts collaborated in the choice of the yearly consuls, as each court chose a consul and accepted the other's choice. Anthemius had the honour of holding the consulate sine collega (without a colleague) in 468, the first year he started as Emperor, following a similar honour given to Leo in 466. The following year the two consuls were Anthemius' son, Marcian, and Leo's son-in-law, Flavius Zeno (later successor of Leo on the Eastern throne).

In 470 the consuls were Messius Phoebus Severus, Anthemius' old friend and fellow student at Proclus' school, and the Magister militum per Orientem Flavius Iordanes. In 471, the year in which Leo held his fourth consulate with the Praetorian prefect of Italy Caelius Aconius Probianus as colleague, the two emperors strengthened their bonds with a marriage between Anthemius' son, Marcian, and Leo's daughter, Leontia; Marcian was honoured with his second consulate the following year, this time chosen by the Eastern court.

Anthemius' matrimonial policy also included the marriage of his only daughter, Alypia, and the powerful Magister militum Ricimer. The poet Sidonius Apollinaris arrived in Rome on the occasion of the wedding at the end of 467 and described the celebrations in which all social classes were involved; he also hints that Alypia might have not liked her husband, a barbarian.[11]

Campaigns against the Vandals

[edit]

The Vandals were the major problem of the Western Empire. In late 467, Anthemius organised a campaign of the western Roman army, probably under the command of Marcellinus. The campaign to overthrow the Vandals was on a large scale, with more than 100,000 men.[12] However, the war would end in failure: the bad weather obliged the Roman fleet to return to its base before completing the operation.

In 468, Leo the Thracian, Anthemius and Marcellinus organized a major operation against the Vandal Kingdom in Africa. The commander-in-chief of the operation was Leo's brother-in-law Basiliscus (who would become Eastern emperor seven years later). A fleet consisting of upwards of one thousand vessels was collected to transport the combined Eastern-Western-Illyric army, and while most of the expenses were paid for by the Eastern Empire, Anthemius and the Western treasury contributed to the costs. The Roman fleet took a massive defeat at the Battle of Cape Bon due to Basiliscus allowing Gaiseric five days to draw up conditions for a peace, which he used to gather his ships and surprise attack the Roman fleet, destroying at least half of the Roman ships.[12] Basiliscus escaped the battle to Sicily to meet with Marcellinus, although Marcellinus was later killed by an assassin.

Leo decided to sign a separate peace with Gaiseric. Anthemius lost his allies and, with the imperial treasury almost emptied by the failed operation, renounced taking Africa back. Peter Heather considers this expedition to have been the final opportunity to restore the Empire, which from this point would now only control the Italian peninsula and Sicily.[13]

Campaigns against the Visigoths

[edit]After the disastrous campaign in Africa, Anthemius concentrated on the second problem of his Empire, keeping under his control the Western provinces targeted by Visigothic expansion. He turned to the reconquest of Gaul, occupied by Visigoths under the ambitious King Euric who had exploited the weak Roman control caused by political instability. Euric's sphere of influence had also separated some imperial provinces from the rest of the Empire. Even though Arelate and Marseilles in Southern Gaul were still governed by the Western court, Avernia was isolated from the rest of the Empire and governed by Ecdicius, son of Emperor Avitus, while the territory later included in the so-called Domain of Soissons was located further north.

In 470, Anthemius recruited Britons living in either Britain or Armorica to fight Euricus.[14] The Britons, under King Riothamus, were initially successful and occupied Bourges with twelve thousand men. However, when they entered the core of Visigoth territory, trying to conquer Déols, they were outnumbered and defeated by a Visigoth army, and Riothamus was forced to flee to the Burgundians, who were Roman allies.[15]

Anthemius took the matter into his own hands and decided to attack the Visigoths directly. He collected an army under the nominal leadership of his own son, Anthemiolus, but actually commanded by the generals Torisarius, Everdingus, and Hermianus. Anthemiolus moved from Arelate and crossed the Rhone river, but he was intercepted by Euric, who defeated and killed the Roman generals and pillaged the area.[16]

Internal affairs and relationship with the Roman Senate

[edit]While Africa was lost and the control over Western provinces was shaky, Anthemius' power over Italy was threatened by internal opposition; he was of Greek origin, had been chosen by the Eastern Emperor from among members of the Eastern court, and was suspected of being a pagan.[b]

In order to obtain the support of the senatorial aristocracy, Anthemius conferred the rank of patricius on members of the Italian and Gallic governing class. He introduced the practice, common in the East, of appointing even civilians to the patrician rank, and honoured so many members of the aristocracy with this title that it suffered a sort of inflation. Among the new patricii there were Italian senators, e.g. Romanus and Messius Phoebus Severus, but against common practice he also appointed Gallic senators and even aristocrats without noteworthy careers, such as Magnus Felix and the Gallic poet Sidonius Apollinaris.

Sidonius had come to Rome to bring a petition from his people; his contact in the court, the consul Caecina Decius Basilius, suggested that he should compose a panegyric to be performed at the beginning of Anthemius' consulate, on 1 January 468. The Emperor honoured the poet, conferring on him the patrician rank, the high rank of Caput senatus, and even the office of Praefectus urbi of Rome, usually reserved to members of the Italian aristocracy.[17] Sidonius was so influential that he convinced the Emperor to commute the death penalty of Arvandus, the Praetorian prefect of Gaul who had allied himself with the Visigoths.

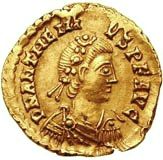

Coinage

[edit]

The good relationship between the two Roman Emperors was good news in the recent affairs between the two halves of the Roman Empire, and was used in imperial propaganda. Anthemius had his mints (at Mediolanum, Ravenna and Rome) issue solidi depicting the two Emperors joining hands in a show of unity.

Anthemius had restored his court in Rome, and thus this mint became more and more important, overshadowing the other two mints.

Some coins are in the name of his wife Marcia Euphemia; among these there is a solidus depicting two Empresses on the thrones, probably a reference to Alypia's marriage.

Death

[edit]

The most important figure at the Western court was Ricimer, the powerful magister militum, who had already decided the fate of several emperors.[19] The new emperor, however, had been chosen by the Eastern court, and, despite the bond of the marriage between Ricimer and Anthemius' daughter, Alypia, they were not on good terms. The tipping point of their relationship was the trial of Romanus, an Italian senator and patricius supported by Ricimer; Anthemius accused Romanus of treachery and condemned him to death in 470.[20]

Ricimer had gathered 6,000 men for the war against the Vandals, and after the death of Romanus he moved with his men to the north, leaving Anthemius in Rome. Supporters of the two parties fought several brawls, but Ricimer and the emperor signed a one-year truce after the mediation of Epiphanius, the Bishop of Pavia.[21]

At the beginning of 472, the struggle between them renewed, and Anthemius was obliged to feign an illness and took refuge in St. Peter's Basilica. The Eastern Roman emperor, Leo, sent Olybrius to mediate between Ricimer and Anthemius but, according to John Malalas, had sent a secret letter to Anthemius, urging him to kill Olybrius. Ricimer intercepted the letter, showed it to Olybrius, and had him proclaimed emperor.[22]

The struggle became an open war. Anthemius, with the aristocracy and the people of the city, faced the Gothic magister militum and the barbarian units of the army, which included Odoacer's men. Ricimer blockaded Anthemius in Rome; five months of fighting followed. Ricimer entered the city and succeeded in separating the port on the Tiber from the Palatine, starving the supporters of the emperor.[23]

Both sides appealed to the army in Gaul, but the Magister militum per Gallias, the Burgundian Gundobad, supported his uncle Ricimer. Anthemius elevated Bilimer to the rank of Rector Galliarum and had him enter Italy with the loyal army. Bilimer arrived in Rome but died trying to prevent Ricimer entering the centre of the city from the other side of the Tiber, through the Pons Aelius in front of the Mausoleum of Hadrian.[24]

Losing any hope of external help and pressed by the scarcity of food, Anthemius tried to rally, but his men were defeated and killed in great numbers.[23] The emperor fled for the second time to St. Peter's (or, according to other sources, to Santa Maria in Trastevere), where he was captured and beheaded by Gundobad[23][25] or by Ricimer[26] on 11 July 472.[27]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Although Anthemius is generally understood to have, at least nominally, been a Christian, he was presumed to be pagan by some contemporary sources.

- ^ Anthemius had many pagans as collaborators: Marcellinus was a pagan, as was Anthemius' friend, the philosopher, Consul of 470 and Praefectus urbi, Messius Phoebus Severus.

References

[edit]- ^ PLRE, "Anthemius 3", p. 96.

- ^ His full name is only known by a few coins. Kent, John (2018). Roman Imperial Coinage. Volume X. Spink Books. p. 411. ISBN 978-1-912667-37-6.

- ^ PLRE, "Procopius 2", p. 920.

- ^ O'Meara, Dominic, Platonopolis: Platonic Political Philosophy in Late Antiquity, Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-19-925758-2, p. 21.

- ^ John Malalas, Chronicon, 368–369, cited in Mathisen.

- ^ Mathisen (1998).

- ^ Thompson, Edward Arthur, The Huns, Blackwell Publishing, 1996, ISBN 0-631-21443-7, p. 170.

- ^ Fasti vindobonenses priores, no. 597, s.a. 467: "his cons. levatus est imp. do.n. Anthemius Romae prid. idus Aprilis.", cited in Mathisen.

- ^ Dioscorus was the teacher of Leo's daughters, Ariadne and Leontia, and later became Praetorian prefect of the East.

- ^ Justinian code, I.11.8, issued on 1 July 472, cited in Mathisen.

- ^ Sidonius Apollinaris, Epistulae, i.5.10–11.

- ^ a b Bury, J.B. (1923). History of the later Roman Empire : from the death of Theodosius I to the death of Justinian (A.D. 395 to A.D. 565). Vol. 1. London: Macmillan. p. 336. ISBN 9781375904957.

- ^ Heather, Peter (11 June 2007). The Fall of the Roman Empire. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-532541-6.

- ^ Chronica gallica anno 511, n. 649, s.a. 470; Sidonius Apollinaris, Epistulae III.9

- ^ Jordanes, 237–238; Gregory of Tours, ii.18.

- ^ Chronica gallica anno 511, n. 649 s.a. 471, cited in Mathisen.

- ^ Sidonius Apollinaris, Epistulae, i.9.1–7.

- ^ "Roman Imperial Coinage – RIC IX, Antioch".

- ^ Ricimer had deposed Avitus and Majorian and supported the election of Libius Severus.

- ^ Cassiodorus, Chronicon, 1289; Paul the Deacon, Historia Romana, xv.2; John of Antioch, fragments 209.1–2, 207, translated by C.D. Gordon, The Age of Attila (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1966), pp. 122f

- ^ Magnus Felix Ennodius, Vita Epiphanii, 51–53, 60–68; Paul the Deacon, Historia Romana, xv.203.

- ^ John Malalas, Chronographica, 373–374.

- ^ a b c John of Antioch, fragment 209.1–2; translated by C.D. Gordon, The Age of Attila, pp. 122f.

- ^ Paul the Deacon, Historia Romana, xv.4.

- ^ John Malalas, Chronographica, 37.

- ^ Cassiodorus, Chronicle, 1293; Marcellinus Comes, Chronicon, s.a.472; Procopius of Caesarea, Bellum Vandalicum, vii.1–3. Chronica gallica anno 511 (n. 650, s.a. 472) records both versions.

- ^ Fasti vindobonenses priores, n. 606, s.a. 472.

Bibliography

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]Sources for Anthemius's life are richer than for most fifth century Western Emperors, partly because of his origin in Constantinople, where the tradition of court histories was kept alive, and partly because of the details that can be extracted from a panegyric delivered on 1 January 468 by the Gallo-Roman poet Sidonius Apollinaris.

- Gregory of Tours, Historia Francorum

- Jordanes, Getica

- Sidonius Apollinaris, Epistulae and Carmen

Secondary sources

[edit]- Mathisen, Ralph W. (1998). "Anthemius (12 April 467 – 11 July 472 A.D.)". De Imperatoribus Romanis. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Morris, John; Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Martindale, John Robert (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07233-6.