Anti-Russian sentiment

Anti-Russian sentiment or Russophobia is dislike or fear or hatred of Russia, Russian people, or Russian culture. The opposite of Russophobia is Russophilia.

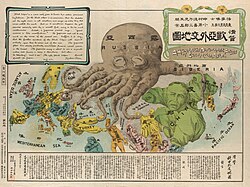

Historically, Russophobia has included state-sponsored and grassroots mistreatment and discrimination, as well as propaganda containing anti-Russian sentiment.[1][2] In Europe, Russophobia was based on various more or less fantastic fears of Russian conquest of Europe, such as those based on The Will of Peter the Great forgery documented in France in the 19th century and later resurfacing in Britain as a result of fears of a Russian attack on British-colonized India in relation to the Great Game. Pre-existing anti-Russian sentiment in Germany is considered to be one of the factors influencing treatment of Russian population under German occupation during World War II.

Nowadays, a variety of popular culture clichés and negative stereotypes about Russians still exist, notably in the Western world.[3] Some individuals may have prejudice or hatred against Russians due to history, racism, propaganda, or ingrained stereotypes.[4][5][6][7][8] Negative views of Russia are widespread, but most prevalent in Western liberal democracies.[9][10][11]

Some analysts have argued that official Western rhetoric and journalism about Russian actions abroad have contributed to the resurgence of anti-Russian sentiment, besides disapproval of the Second Chechen War, Russian reaction to NATO enlargement, the 2008 Russo-Georgian war and Russian interference in the 2016 United States election.[12][13][14] Anti-Russian sentiment rose considerably after the start of the Russian war against Ukraine in 2014.[15] By the summer of 2020, majority of Western nations had unfavorable views of Russia.[16]

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian-speaking immigrants experienced harassment, open hostility and discrimination.[17][18][19]

Some researchers have described use of "Russophobia" narratives to be a tactic used by Vladimir Putin. These narratives emphasizes the belief that Russia faces an existential threat from the Western powers and must take drastic measures to ensure domestic stability including support for the ongoing war in Ukraine. Such narratives have been described as Russian imperialism.[20][21][22]

History in Europe

Anti-Russian sentiment in Europe has a long history, dating back several centuries. Initially, it was largely driven by religious and cultural differences, as well as Russia's expansionist policies.[23]: 114–115 This sentiment has evolved over time, but the underlying themes of perceived barbarism, imperialism, and cultural inferiority have remained constant.[23]: 104–105

15th to 17th century

Negative views of Russia in Europe began to take shape in the 15th century during the period of Russian expansion into non-Russian lands under Ivan III. Russia's campaigns against Poland-Lithuania, Livonian cities, and Swedish-held Finland marked the beginning of a perception of Russia as a threat. During this era, Russia was often portrayed as a barbaric, un-Christian, and imperialistic nation by its European adversaries.[23]: 104–105 Michael C. Paul argued that the crusades of the 13th century against Russian Christian cities like Novgorod and Pskov may highlight even more deeply rooted religious and cultural animosity.[23]: 106

During the Livonian War (1558–83), European powers, particularly Poland-Lithuania and the Livonian German cities, intensified their negative perception of Russia. They imposed embargoes on war supplies to Russia, fearing the possibility of it receiving military supplies from England, which had an active trade mission in Russia. Queen Elizabeth denied the accusations.[23]: 106–107

Contemporaries described Tsardom of Russia and early Russian Empire as a barbaric enemy of Christianity. Accounts by Western travelers like Austrian Ambassador Sigismund von Herberstein and English Ambassador Giles Fletcher in the 16th century portrayed Russia in a negative light, focusing on aspects like superstition, brutality, and backwardness. Negative views persisted into the 17th and 18th centuries, with Western observers continuing to highlight aspects like superstition, drunkenness, and barbaric practices in Russian society. Notable figures like Captain John Perry and French travelers Jacques Margeret and Jean Chappe d'Auteroche contributed to these perceptions, often comparing Russian society unfavorably with Western standards.[23]: 107–109

18th and 19th centuries

On 19 October 1797, the French Directory received a document from a Polish general, Michał Sokolnicki, entitled "Aperçu sur la Russie". This forgery is known as the so-called "The Will of Peter the Great" and was first published in October 1812, during the Napoleonic wars, in Charles Louis-Lesur's much-read Des progrès de la puissance russe: this was at the behest of Napoleon I, who ordered a series of articles to be published showing that "Europe is inevitably in the process of becoming booty for Russia".[25][26] Subsequent to the Napoleonic wars, propaganda against Russia was continued by Napoleon's former confessor, Dominique Georges-Frédéric de Pradt, who in a series of books portrayed Russia as a power-grasping "barbaric" power hungry to conquer Europe.[27] With reference to Russia's new constitutional laws in 1811 the Savoyard philosopher Joseph de Maistre wrote the now famous statement: "Every nation gets the government it deserves" ("Toute nation a le gouvernement qu'elle mérite").[28][29]

Beginning from 1815 and lasting roughly until 1840, British commentators began criticizing the perceived conservatism of the Russian state and its resistance to reform efforts.[30] In 1836, The Westminster Review attributed growth of British navy to "Ministers [that] are smitten with the epidemic disease of Russo-phobia".[31] However, Russophobia in Britain for the rest of the 19th century was primarily related to British fears that the Russian conquest of Central Asia was a precursor to an attack on British-colonized India. These fears led to the "Great Game", a series of political and diplomatic confrontations between Britain and Russia during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[32]

In 1843 the Marquis de Custine published his hugely successful 1800-page, four-volume travelogue La Russie en 1839. Custine's scathing narrative reran what were by now clichés which presented Russia as a place where "the veneer of European civilization was too thin to be credible". Such was its huge success that several official and pirated editions quickly followed, as well as condensed versions and translations in German, Dutch, and English. By 1846 approximately 200 thousand copies had been sold.[33]

In 1867, Fyodor Tyutchev, a Russian poet, diplomat and member of His Imperial Majesty's Own Chancellery, introduced the actual term of "russophobia" in a letter to his daughter Anna Aksakova on 20 September 1867,[citation needed] where he applied it to a number of pro-Western Russian liberals who, pretending that they were merely following their liberal principles, developed a negative attitude towards their own country and always stood on a pro-Western and anti-Russian position, regardless of any changes in the Russian society and having a blind eye on any violations of these principles in the West, "violations in the sphere of justice, morality, and even civilization". He put the emphasis on the irrationality of this sentiment.[34] Tyutchev saw Western anti-Russian sentiment as the result of misunderstanding caused by civilizational differences between East and West.[35]

German atrocities in World War II

Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party regarded Slavic peoples (especially Poles and East Slavs) as non-Aryan Untermenschen (subhumans).[36] As early as 1925, Hitler suggested in Mein Kampf that the German people needed Lebensraum ("living space") to achieve German expansion eastwards (Drang nach Osten) at the expense of the inferior Slavs. Hitler believed that "the organization of a Russian state formation was not the result of the political abilities of the Slavs in Russia, but only a wonderful example of the state-forming efficacity of the German element in an inferior race."[37]

After the invasion of the Soviet Union, Hitler expressed his plans for the Slavs:

As for the ridiculous hundred million Slavs, we will mold the best of them as we see fit, and we will isolate the rest of them in their pig-styes; and anyone who talks about cherishing the local inhabitants and civilizing them, goes straight off into a concentration camp![38]

Plans to eliminate Russians and other Slavs from Soviet territory to allow German settlement included starvation. American historian Timothy D. Snyder maintains that there were 4.2 million victims of the German Hunger Plan in the Soviet Union, "largely Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians," including 3.1 million Soviet POWs and 1.0 million civilian deaths in the Siege of Leningrad.[39] According to Snyder, Hitler intended eventually to exterminate up to 45 million Slavs by planned famine as part of Generalplan Ost.[40]

Influenced by the guidelines, in a directive sent out to the troops under his command, General Erich Hoepner of the 4th Panzer Army stated:

The war against Russia is an important chapter in the German nation's struggle for existence. It is the old battle of the Germanic against the Slavic people, of the defense of European culture against Muscovite-Asiatic inundation and the repulse of Jewish Bolshevism. The objective of this battle must be the demolition of present-day Russia and must, therefore, be conducted with unprecedented severity. Every military action must be guided in planning and execution by an iron resolution to exterminate the enemy remorselessly and totally. In particular, no adherents of the contemporary Russian Bolshevik system are to be spared.[41]

Cold War

Russophobic stereotypes of an illiberal tradition were also favored by Cold War historiographers, even as scholars of early Russia debunked such essentialist notions.[42]

Widely criticized for being antisemitic and extremist nationalistic, Igor Shafarevich's 1981 work Russophobia[43] blamed "Jews seeking world rule" for alleged "vast conspiracy against Russia and all mankind" and seeking destruction of Russia through adoption of a Western-style democracy.[44]

After 1989

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the collapse of Communism, anti-Russian sentiment in the United States was at an all-time low. However, it has experienced a resurgence during the late 1990s due to Russia's opposition to the enlargement of NATO. According to a Gallup poll, 59% of surveyed Americans viewed Russia negatively in 1999, compared to 25% in 1991.[45]

Anatol Lieven considered the Western commentary on the Second Chechen War and a Russian reaction to eastward NATO enlargement to be the main cause of growing Russophobia in the 90s. Condemning the brutality of the Russian army and an exaggerated fear of NATO, he argued that the influence of the § Cold War elites and ethnic lobbies, coupled with 19th century stereotypes about Russian expansionism led Western journalists and intellectuals to drop professional standards and engage in propaganda, spreading Russophobia and national hatred.[12] In April 2007, David Johnson, founder of the Johnson's Russia List, said in interview to the Moscow News: "I am sympathetic to the view that these days Putin and Russia are perhaps getting too dark a portrayal in most Western media. Or at least that critical views need to be supplemented with other kinds of information and analysis. An openness to different views is still warranted."[46] California-based international relations scholar Andrei Tsygankov has remarked that anti-Russian political rhetoric coming from Washington circles has received wide echo in American mainstream media, asserting that "Russophobia's revival is indicative of the fear shared by some U.S. and European politicians that their grand plans to control the world's most precious resources and geostrategic sites may not succeed if Russia's economic and political recovery continues."[47] In contrast, Krystyna Kurczab-Redlich and some other reporters active in Chechnya alarmed already in early 2000s that Putin's true nature and intentions have been exposed by the Russian atrocities during the Second Chechen War as by no means resembling those of a Western democrat. It was, however, convenient for the Western elites to brand these reports as Russophobic and disregard them, in spite of such reports being delivered also by Anna Politkovskaya, a Russian journalist and human rights activist, later assassinated.[48][49] The first among these views has ultimately suffered utter discreditation in a humiliating manner after 2014, primarily because it was inherently flawed as it focused exclusively on the fantastic motivations behind anti-Russian sentiment in Western Europe, while entirely disregarding the precisely specified reasons of negative views of Russia in Central and Eastern Europe which stem in turn from real experience and knowledge.[50][51][52]

In October 2004, the International Gallup Organization announced that according to its poll, anti-Russia sentiment remained fairly strong throughout Europe and the West in general. It found that Russia was the least popular G-8 country globally. Overall, the percentage of respondents with a positive view of Russia was only 31%.[53]

Anti-Russian sentiment in the United States and Western European countries decreased during the presidency of Dmitry Medvedev, with about half of respondents in US, UK, Germany, Spain and France having positive views of Russia in 2011. It began to increase again after 2012.[16] The Transatlantic Trends 2012 Report indicated that "views of Russia turned from favorable to unfavorable on both sides of the Atlantic", noting that most Americans and Europeans, as well as many Russians, said that they were not confident that the election results expressed the will of voters.[54]

Attitudes towards Russia in most countries worsened considerably following Russia's annexation of Crimea, the subsequent fomenting of the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine and its intervention in the resulting War in Donbas. From 2013 to 2014, the median negative attitudes in Europe rose from 54% to 75%, and from 43% to 72% in the United States. Negative attitudes also rose compared to 2013 throughout the Middle East, Latin America, Asia and Africa.[15]

According to political scientist Peter Schulze, the accusations of collusion with Trump campaign, coupled with the criminal case of Lisa F., which was reported in Germany as an instance of Russia's hybrid war, sparked fears that the Kremlin could meddle in German campaigns as well, resulting in growth of anti-Russian sentiment in Germany after 2016.[55]

By the summer of 2020, majority of Western nations had unfavorable views of Russia, with an exception of Italy, which was attributed by Pew Research Center to a delivery of medical aid by Moscow early during the pandemic.[16]

85% of Americans polled by Gallup between 1 and 17 February 2022 had unfavorable view of Russia.[45]

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

There was a sharp uptick in manifestations of anti-Russian sentiment after the beginning of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine;[56][57] following the start of the invasion, anti-Russian sentiment soared across the Western world.[54][58][59][60][61] Since the invasion commenced, ethnic Russians and Russian-speaking immigrants from post-Soviet states are globally reporting rising instances of open hostility and discrimination towards them.[19][18] This hostility is not just towards Russian people; it has also been seen directed towards businesses as well.[62]

A "pervasive climate of distrust" towards Russian passport holders in Europe and rejections of bank account applications because of nationality were reported.[63] United Kingdom limited how much Russian nationals are allowed to save on bank accounts. The banking industry considered the restriction to violate UK equality laws, which forbid discrimination by nationality.[64] Leonid Gozman called European restrictions discriminatory and said that they harmed dissidents who were forced to leave Russia, leaving them without means to survive.[65]

Outrage was caused by pro-war demonstrations held in Athens, Berlin, Dublin, Hanover, Frankfurt and Limassol, consisting of "vehicles emblazoned with the pro-war Z symbol and marches attended by hundreds of flag-waving nationalists". Experts surveyed by The Times said that the rallies were likely coordinated by the Kremlin via the soft power Rossotrudnichestvo agency, stressing that a "bottom-up element" of support for Russia also exists.[66]

By 2023, the most negative perception of Russia was in Ukraine (net negative 79%), followed by Portugal with 69%, Japan with 68%, and Poland with 68%, according to the 2023 Democracy Perception Index.[67]

As a polemic device

The Kremlin and its supporters are sometimes criticised for using allegations of "Russophobia" as a form of propaganda to counter criticism of government policy.[68][22] Sources critical of the Russian government claim that it is Russian state-owned media and administration who attempt to discredit the "neutral" criticism by generalizing it into indiscriminate accusations of the whole Russian population – or Russophobia.[22][69][70] In 2006, poet and essayist Lev Rubinstein wrote that similarly to the term "fascism", the term "Russophobia" has become a political sticker slapped onto people who disagree with words or actions of people or organizations who position themselves as "Russian ones" in the ideological, rather than an ethnic or geographical sense.[71]

Russian responses to outside anti-Russian criticism has intensified the growth of contemporary Russian nationalist ideology, which in many ways mirrors its predecessor, Soviet nationalism.[22][72] Sociologist Anatoly Khazanov states that there's a national-patriotic movement which believes that there's a "clash of civilizations, a global struggle between the materialistic, individualistic, consumerist, cosmopolitan, corrupt, and decadent West led by the United States and the idealist, collectivist, morally and spiritually superior Eurasia led by Russia."[73] In their view, the United States wants to break up Russia and turn it into a source of raw materials. The West being accused of Russophobia is a major part of their beliefs.[74]

Joseph Stiglitz wrote that these attitudes are reinforced by the failure of the post-Soviet liberal economic reforms, which are perceived to have been influenced by the US Treasury.[75] A mismatch between U.S. rhetoric about promoting democratic reforms in Russia and actual U.S. actions and policy has been said to cause deep resentment among Russians, helping Russian propaganda to construct a narrative of U.S. malign interference.[76]

Since the 2014 annexation of Crimea and subsequent sanctions, there was a rapid growth of charges of Russophobia in the official discourse. Use of the term on the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs website rose dramatically during the period between 2014 and 2018.[77] Russian President Vladimir Putin compared Russophobia to antisemitism.[78][79][80] Academic Jade McGlynn considered conflation of modern Russophobia and Nazi antisemitism to be a part of propaganda strategy that uses historical framing to create a flattering narrative that the Russo-Ukrainian War is a restaging of the Great Patriotic War.[81][82] Kathryn Stoner and Michael McFaul explained the turn to radical nationalism as a strategy to preserve the regime within domestic economical and political pressures, claiming that "To maintain his argument for legitimacy at home, Putin needs... constant confrontation that supports the narrative that Russia is under siege from the West, that Russia is at war with the United States."[20]

A Russian political scientist and a senior visiting fellow at the George Washington University Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies Maria Lipman said that this narrative was made more convincing by imposing sanctions on Russia and supporting Ukraine with weapons, as well as by statements about weakening Russia made by American establishment, amplified on Russian television.[83]

The Washington Post reported effectiveness of using the label of "Russophobia" by Russian propaganda to sustain support for the invasion of Ukraine by presenting it as an existential confrontation with the West. According to an independent polling agency, "people explain that a significant part of the world is against us and it's only Putin who hopes to hold onto Russia, otherwise we would be eaten up completely. To them it is Russia that is defending itself".[21]

By country

| Democracy Perception Index 2024[84][85] "What is your overall perception of Russia?" (default-sorted by decreasing negativity of each country) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country polled | Positive | Negative | Neutral | Difference |

| -87 | ||||

| -75 | ||||

| -71 | ||||

| -70 | ||||

| -68 | ||||

| -63 | ||||

| -61 | ||||

| -56 | ||||

| -55 | ||||

| -55 | ||||

| -53 | ||||

| -52 | ||||

| -52 | ||||

| -51 | ||||

| -50 | ||||

| -50 | ||||

| -47 | ||||

| -45 | ||||

| -39 | ||||

| -37 | ||||

| -36 | ||||

| -33 | ||||

| -32 | ||||

| -30 | ||||

| -28 | ||||

| -23 | ||||

| -19 | ||||

| -18 | ||||

| -16 | ||||

| -14 | ||||

| -11 | ||||

| -2 | ||||

| +1 | ||||

| +1 | ||||

| +5 | ||||

| +7 | ||||

| +13 | ||||

| +14 | ||||

| +16 | ||||

| +16 | ||||

| +18 | ||||

| +28 | ||||

| +29 | ||||

| +30 | ||||

| +33 | ||||

| +35 | ||||

| +45 | ||||

| +48 | ||||

| +48 | ||||

| +53 | ||||

| +53 | ||||

| +58 | ||||

| +78 | ||||

South Caucasus

Armenia

After Nicholas II intensified russification policies and did not provide significant opposition to the Ottoman Empire's massacres against Armenians, anti-Russian sentiment among Armenian nationalist groups rose. After the Russian government confiscated Armenian Church lands in 1903, this led to attacks on Russian authorities and Armenians who cooperated with them by Armenians mobilised by the ARF party.[86]

In July 1988, during the Karabakh movement, the killing of an Armenian man and the injury of tens of others by the Soviet army in a violent clash at Zvartnots Airport near Yerevan sparked anti-Russian and anti-Soviet demonstrations.[87] In 2015, relations between Armenia and Russia were strained after the massacre of an Armenian family of 7 in Gyumri by a Russian serviceman, stationed at the Russian base there.[88][89]

Relations between Armenia and Russia have worsened in recent years, due to Russia's refusal to help Armenia in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war and the September 2022 Armenia–Azerbaijan clashes,[90] as well as due to statements perceived to be anti-Armenian made by figures close to Russian President Vladimir Putin.[91] This has resulted in anti-Russian sentiment rising sharply in the country.[92]

Azerbaijan

The 1990 Black January massacre prior to Azerbaijani independence and Russia's complicated role in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War between Azerbaijan and Armenia increased the negative perception of Russia.[93] Under Abulfaz Elchibey's presidency in 1992–93, relations between Russia and Azerbaijan were damaged due to his anti-Russian policies,[94] however under Ilham Aliyev, relations instead improved.[95]

Georgia

There has been increased animosity towards Russians in Tbilisi after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has also been directed towards exiled Russians who recently fled their home country. It has included signs from businesses and posts from Airbnb hosts declaring “Russians not welcome”, anti-Russian graffiti found on many central streets, the famous Bassiani nightclub banning anyone with a Russian passport, and an online petition signed by thousands of locals demanding tougher immigration rules for Russians.[96][97]

Accordingly, in March 2022 a strong majority of 84% of respondents to a Georgian poll said Russia is the enemy of Georgia,[98] a sharp uptick compared with a decade earlier. According to a 2012 poll, 35% of Georgians perceived Russia as Georgia's biggest enemy.[99] Furthermore, in a February 2013 poll a majority of 63% said Russia is Georgia's biggest political and economic threat as opposed to 35% of those who looked at Russia as the most important partner for Georgia.[100] In November 2023, 11% preferred closer ties with Russia, while abandoning western ties, and 25% wanted to deepen ties with Russia.[101]

The root of the Georgian anti-Russian sentiment lies in the history of Russian colonialism of Transcaucasia. For Georgians, the country was twice occupied and annexed by Russia. First in 1801 under the Tsarist regime, and then, after a short interlude of independence of the Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918–1921), a 70-year period of forceful Soviet occupation.[102] This sentiment was further fed by the events of the 1990s, when Russia supported the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, two historically inalienable parts of Georgia, causing the Abkhaz–Georgian conflict, the Georgian–Ossetian conflict and later the war with Russia in 2008.[103] It was also followed by Georgian sympathy to the Chechens during the Chechen–Russian conflict of the 1990s.[104]

Rest of Europe

In a 2012 survey, the percentage of Russian immigrants in the EU that indicated that they had experienced racially motivated hate crimes was 5%, which is less than the average of 10% reported by several groups of immigrants and ethnic minorities in the EU.[105] 17% of Russian immigrants in the EU said that they had been victims of crimes in the preceding 12 months, as compared to an average of 24% among several groups of immigrants and ethnic minorities.[106]

Baltics

In 2015, the chairman of the Russian State Duma's Foreign Affairs Committee Aleksey Pushkov alleged that Russophobia had become the state policy in the Baltic states[107] and in 2021 Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov accused the Baltic states of being "the leaders of the Russophobic minority" in NATO and the European Union.[108]

Estonia

This section may be unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. (August 2021) |

A poll conducted by Gallup International suggested that 34% Estonians have a positive attitude towards Russia, but it is supposed that survey results were likely impacted by a large ethnic Russian minority in the country.[53] However, in a 2012 poll only 3% of the Russian minority in Estonia reported that they had experienced a hate crime (as compared to an average of 10% among ethnic minorities and immigrants in EU).[105]

According to Estonian philosopher Jaan Kaplinski, the birth of anti-Russian sentiment in Estonia dates back to 1940, as there was little or none during the czarist and first independence period, when anti-German sentiment predominated. Kaplinski states the imposition of Soviet rule under Joseph Stalin in 1940 and subsequent actions by Soviet authorities led to the replacement of anti-German sentiment with anti-Russian sentiment within just one year, and characterized it as "one of the greatest achievements of the Soviet authorities".[109] Kaplinski supposes that anti-Russian sentiment could disappear as quickly as anti-German sentiment did in 1940, however he believes the prevailing sentiment in Estonia is sustained by Estonia's politicians who employ "the use of anti-Russian sentiments in political combat," together with the "tendentious attitude of the [Estonian] media."[109] Kaplinski says that a "rigid East-West attitude is to be found to some degree in Estonia when it comes to Russia, in the form that everything good comes from the West and everything bad from the East";[109] this attitude, in Kaplinski's view, "probably does not date back further than 1940 and presumably originates from Nazi propaganda."[109]

Latvia

According to The Moscow Times, Latvia's fears of Russia are rooted in recent history, including conflicting views on whether Latvia and other Baltic states were occupied by the USSR or joined it voluntarily, as well as the 1940–1941 June and 1949 March deportations that followed and more recently the annexation of Crimea that fueled a fear that Latvia could also be annexed by Russia.[110] Russian-American journalist and broadcaster Vladimir Pozner believed the fact that many Russian migrants in the Latvian SSR did not learn Latvian and expected the local population to speak Russian also contributed to an accumulation of anti-Russian sentiment.[111]

No Russians have ever been killed or even wounded for political, nationalistic or racist reasons in Latvia ever since it regained its independence[112][113][114] and in a 2012 poll only 2% of the Russian minority in Latvia reported having experienced a 'racially' motivated hate crime (as compared to an average of 10% among immigrants and minorities in EU).[105] An earlier 2004 research "Ethnic tolerance and integration of the Latvian society" by the Baltic Institute of Social Sciences found that Latvian respondents on average rated their relations with Russians 7.8 out of 10, whereas non-Latvian respondents rated their relationship with Latvians 8.4 out of 10. Both groups believed that the ties between them were satisfactory, had not changed in the last five years and were to either remain the same or improve in the next five years. 66% of non-Russian respondents said they would also support their son or daughter marrying an ethnic Russian. Respondents did mention some ethnic conflicts, but all of them were classified as psycholinguistic such as verbal confrontations.[115]

Occasionally, Russians in Latvia have been targeted by anti-Russian rhetoric from some of the more radical members of both the mainstream and radical right parties in Latvia. In 2010, Civic Union's internal e-mail correspondence between Minister for Foreign Affairs of Latvia Ģirts Valdis Kristovskis and Latvian American doctor and party member Aivars Slucis was leaked.[116] In one of the e-mails titled "Do Latvians Surrender?"[117] Slucis complained of the current situation in Latvia and being unable to return and work in Latvia, because he would not be able to treat Russians in the same way as Latvians.[117][118] Kristovskis agreed with his opinion and evaluation,[117] but warned against hysterical responses, cautioning party members to avoid discussions counterproductive to the party's political goals. After the leak the Civic Union ousted Slucis from the party for views unacceptable to the party and returned his financial contributions, while the opposition parties Harmony Centre and For a Good Latvia initiated an unsuccessful vote of no confidence against Kristovskis.[118][117]

On the other hand, the results of a yearly poll by the research agency "SKDS" showed that the population of Latvia was more split on its attitude towards the Russian Federation. In 2008, 47 percent of respondents had a positive view of Russia and 33% had a negative one, while the remaining 20 percent found it hard to define their opinion. It peaked in 2010 when 64 percent of respondents felt positive towards Russia, in comparison with the 25 percent that felt negative. In 2015, following the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, however, it dropped to the lowest level since 2008 and for the first time, the people with a negative attitude towards Russia (46%) surpassed people with a positive attitude (41%).[119] 43.5 percent also believed Russia posed a military threat to Latvia and even in 2019 that number had decreased only slightly and stood at 37.3 percent.[120]

Lithuania

Due to historical experiences, there is a fear prevailed in Lithuania that Russia has never stopped wanting to consolidate power over the Baltics, including fears of Russian plans for an eventual annexation of Lithuania as was seen in Crimea.[121] There are also concerns over Russia's increasing military deployment, such as in the Russian region of Kaliningrad, an exclave of Russia bordering Lithuania.[122][123]

Eastern Europe

Romania

Anti-Russian sentiment dates back to the conflict between the Russian and Ottoman empires in the 18th and early 19th centuries and the ceding of part of the Moldavian principality to Russia by the Ottoman Empire in 1812 after its de facto annexation, and to the annexations during World War II and after by the Soviet Union of Northern Bukovina and Bessarabia and the policies of ethnic cleansing, Russification and deportations that have taken place in those territories against ethnic Romanians. Following WWII, Romania, a former ally of Nazi Germany, was occupied by Soviet forces. Soviet dominance over the Romanian economy was manifested through the so-called Sovroms, exacting a tremendous economic toll ostensibly as war-time reparations.[124][125][126][127]

The emergence of anti-Russian sentiment in the Danubian Principalities, the precursors to unified Romania which became independent of the Ottoman Empire with the 1829 Treaty of Adrianople concluding the 1828–1829 Russo-Turkish War, arose from the post-1829 relationship of the Danubian Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia to Russia, and was caused by mutually economic and political grievances of two influential classes that were often odds also with each other. As per the 1829 treaty, Russia was named the protector of the two principalities, allowed to occupy them, and also drafted a quasi-constitution known as the Organic Regulations which formed a powerful assembly of 800 boyars (the local landowning economic elite) nominally under the authority of the less nominal prince, the document crafted with strong support from the boyars. The boyars, a "reactionary oligarchy" as described by Misha Glenny, stopped short any hint of liberal reform, and the growing urban elite began to associate Russia with the slow progress of reform and the obstacles they faced in building an industrial base. On the other hand, the boyars themselves began to sour on Russia during the 1830s and 1840s due to their economic conflict of interest with Russia. After the Ottomans withdrew from the three forts along the Danube basin, the boyars exploited the highly fertile land to drastically increase Romanian wheat production, such that eventually future Romania consisting of Wallachia unified with Moldavia would become the fourth-largest wheat producer in the world. Whereas before 1829 Wallachian and Moldavian wheat had been limited to Ottoman markets, Russia increasingly felt threatened by growing competition in its jurisdiction that it feared could drive down the price of Russian wheat. Accordingly, Russia exploited its role as protector of the Principalities to let the Danube silt up, sabotaging the possible market competitor. As a result of this as well as "Russian foot-dragging on the economy", the boyars too became increasingly resentful of Russian domination. The rapid erosion of public relations with Russia led to a revolution in 1848, in which the newly emerging Romanian intellectual and political class sought the help of the Ottomans, their old hegemon, to drive out Russian influence—although, after pressure applied by Russia, the Russian and Ottoman armies joined forces to squash the movement.[128]

Ukraine

In 2004, the leader of the marginal Svoboda party Oleh Tyahnybok urged his party to fight "the Moscow-Jewish mafia" ruling Ukraine.[129] For these remarks Tyahnybok was expelled from the Our Ukraine parliamentary faction in July 2004.[130] The former coordinator of Right Sector in West Ukraine, Oleksandr Muzychko talked about fighting "communists, Jews and Russians for as long as blood flows in my veins."[131]

In May 2009, a poll held by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in Ukraine said that 96% of respondents were positive about Russians as an ethnic group, 93% respected the Russian Federation and 76% respected the Russian establishment.[132]

In October 2010, statistics by the Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Science of Ukraine said that positive attitudes towards Russians have been decreasing since 1994. In response to a question gauging tolerance of Russians, 15% of Western Ukrainians responded positively. In Central Ukraine, 30% responded positively (from 60% in 1994); 60% responded positively in Southern Ukraine (from 70% in 1994); and 64% responded positively in Eastern Ukraine (from 75% in 1994). Furthermore, 6–7% of Western Ukrainians would banish Russians entirely from Ukraine, and 7–8% in Central Ukraine responded similarly. This level of sentiment was not found in Southern or Eastern Ukraine.[133]

The ultranationalist party Svoboda (once prominent, but now marginal),[134][135][136] has invoked radical anti-Russian rhetoric[137] and has electoral support enough to garner majority support in local councils,[138] as seen in the Ternopil regional council in Western Ukraine.[139] Analysts explained Svoboda's victory in Eastern Galicia during the 2010 Ukrainian local elections as a result of the policies of the Azarov Government who were seen as too pro-Russian by the voters of "Svoboda".[140][141] According to Andreas Umland, Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy,[142] Svoboda's increasing exposure in the Ukrainian media has contributed to these successes.[143] According to British academic Taras Kuzio the presidency of Viktor Yanukovich (2010–2014) fabricated this exposure in order to discredit the opposition.[144] Since the Euromaidan revolution, the Svoboda party lost a lot of its support. In the 2019 Ukrainian parliamentary election Svoboda formed a united party list with the Governmental Initiative of Yarosh, Right Sector and National Corps.[145] The united list received only 2.15% of the votes, less than half of the 5% election threshold, and thus no parliamentary seats via the national party list.[146]

According to the Brookings Institution after Ukraine regained its independence, only a small minority of nationalists expressed strong anti-Russian views; the majority hoped to have good relations with Russia. In 2014, after the Russian annexation of Crimea, the attitude to Russia changed sharply. In April 2017, a poll by Sociological group "RATING" found that 57% of respondents expressed a "very cold" or "cold" attitude toward Russia while 17% expressed a "very warm" or "warm" attitude.[147] In February 2019, 77% of Ukrainians had a positive attitude towards Russians, 57% of Ukrainians had a positive view of Russia, but only 13% of Ukrainians had positive attitude towards the Russian government.[148] Sentiments due to the 2022 war have declined enormously. In March 2022, 97% of Ukrainians said they had an unfavourable view of Russian President Putin, with a further 81% saying they had a very unfavourable or somewhat unfavourable view of the Russian people. However, 65% of Ukrainians agreed that "despite our differences there is more that unites ethnic Russians living in Ukraine and Ukrainians than divides us."[149] Ukrainian officials are working to rid the country's cities of streets named after Russian historical figures like Tchaikovsky or Tolstoy.[150] According to historian at the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv Vasyl Kmet, this is being done to undo the Russian propaganda "of the so-called Russkiy Mir — the Russian-speaking world" by creating "a powerful alternative, a modern Ukrainian national discourse.”[150]

Central Europe

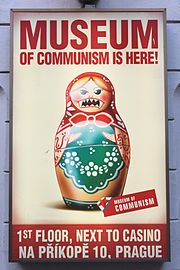

Czech Republic

Russia remains continuously among the most negatively perceived countries among Czechs in polls conducted since 1991, and just 26% of Czechs responded that they had a positive opinion about Russia in November 2016.[151][152][153]

According to writer Tim Nollen in 2008, Russians in Czechia were almost universally disliked as a people due in part to the presence of Russian mafiosi, as well as the "arrogant hordes of Russian visitors that descend upon Prague and the Spas in Karlovy Vary".[154]

Following the start of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, anti-Russian tensions rose in the country.[155][156] Martin Dlouhý, a professor at the Prague University of Economics and Business, wrote on Facebook on February 24 that he would not conduct, test, or correct the final thesis of Russian students “due to conscience and moral principles”; but deleted the post after a strong backlash.[157] Violence in elementary schools prompted attack by students on their ethnic Russian classmates, prompting a condemnation by Prime Minister Petr Fiala.[158] Many Czech shops and restaurants put up signs saying that Russians and Belarusians were not allowed.[159]

Poland

In 2005, The New York Times reported after the Polish daily Gazeta Wyborcza that "relations between the nations are as bad as they have been since the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1989."[160] Jakub Boratyński, the director of international programs at the independent Polish think tank Stefan Batory Foundation, said in 2005 that anti-Russian feelings have substantially decreased since Poland joined the EU and NATO, and that Poles feel more secure than before, but he also admitted that many people in Poland still look suspiciously at Russian foreign-policy moves and are afraid Russia is seeking to "recreate an empire in a different form."[161] According to Boris Makarenko, deputy director of the Moscow-based think tank Center for Political Technologies, much of the modern anti-Russian feelings in Poland is caused by grievances of the past.[161] One contentious issue is the Katyn massacre in 1940 as well as the Stalinist-era ethnic-cleansing operations including the deportation of hundreds of thousands of ethnic Poles, even though the Russian government has officially acknowledged and apologized for the atrocity.[162]

According to a 2013 BBC World Service poll, 19% of Poles viewed Russia's influence positively, with 49% expressing a negative view.[163] According to a Gazeta.pl report in 2019, some Polish hoteliers disliked Russian guests,[164] and the vice president of Poland's Chamber of Tourism admitted back in 2014 that some private guesthouses were rejecting Russian tourists.[165]

Hungary

Hungary's relations with Russia are shadowed by the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 which was crushed with the help of Russian troops[166] as well the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 which was brutally crushed by the Red Army and was followed by the mass arrest and imprisonment of Hungarians.[167][168][169] The current government of Viktor Orbán is seen as friendlier toward Russia.[170] According to a 2019 survey by Pew Research, 3% of Hungarian respondents had a favourable opinion of Russia, 32% had a somewhat favourable opinion, 31% had a somewhat unfavourable opinion and 16% had a very unfavourable opinion.[171]

Northern Europe

Norway

Norway's diplomatic and cultural ties with the West have complicated continuing relations with Russia.[172] A 2017 poll of Norwegians found that 58% believe that Vladimir Putin and Russia pose a security threat.[173]

Russian officials escalated the tensions. A Russian deputy foreign minister stated in Oslo that Russia views the October 2018 Trident Juncture NATO military exercises in Norway to be "anti-Russian" in nature.[174][175] Russian expansion in the Arctic has contributed to increasing mutual distrust between Russia and Norway.[176] Norway's perceptions of Russian militarism and regional antagonism, as well as Norway's hosting of the US Marine Corps in the country, have contributed to the deterioration of relations between Norway and Russia.[175][177]

Finland

In Finland, anti-Russian sentiment has been studied since the 1970s. The history of anti-Russian sentiment has two main theories. One of them claims that Finns and Russians have been archenemies throughout history. The position is considered to have been dominated at least the 1700s since the days of the Greater Wrath. This view largely assumes that through the centuries, "Russia is a violent slayer and Finland is an innocent, virginal victim". Another, perhaps a more plausible view, holds that idea of Russia as the archenemy was only invented during the early years of independence for the purposes of building the national identity.[178]

The Finnish Civil War in 1918 between the Reds and the Whites—won by the Whites—left behind a popular wave of anti-Russian and anti-Communist feelings in Finland.[179] Hundreds of ethnic Russians were executed in 1918 in the city of Vyborg.[180]

According to polls in 2004, 62% of Finnish citizens had a negative view of Russia.[53] In a 2012 poll, 12% of Russian immigrants in Finland reported that they had experienced a racially motivated hate crime (as compared to an average of 10% of immigrants in the EU).[105] A 2012 report by the Ministry of Employment and the Economy said that job applicants with Russian or Russian-sounding names tended to have to send in twice the amount of applications as an applicant with a Finnish name.[181]

Western Europe

France

In the mid 18th century Voltaire gave French intellectuals a positive image, portraying Russia as an opportunity society, in which an all-powerful leaders such as Peter the Great could create a rational and enlightened society by decree. On the other hand, equally influential French enlightenment writers especially Denis Diderot portrayed Russia in dark colours, emphasizing the lack of an enlightenment tradition or a middle class, and a propensity toward harsh dictatorship.[182][183]

Relations between France and Russian during the 19th century oscillated between one of relative friendship to open conflict. French Emperor Napoleon established a military alliance with Russia, before unsuccessfully launching an invasion of the country in 1812 over Russia's refusal to abide by the Continental System. Russophobia in France grew during the 1830s over Russia's suppression of the November Uprising in Poland, with the French public fearing the expansion of a militarily strong "Asiatic" power into Europe. This national mood of Russophobia created support in France for going to war with Russia in 1854.[184][185][186] Fyodor Dostoyevsky noted in A Writer's Diary (1873–1876):

Europeans do not trust appearances: “Grattez le russe et vous verrez le tartare”, they say (scratch a Russian and you'll find a Tatar). That may be true, but this is what occurred to me: do the majority of Russians, in their dealings with Europe, join the extreme left because they are Tatars and have the savage's love of destruction, or are they, perhaps, moved by other reasons?"[187]

According to a 2017 Pew Global Attitudes Project survey, 36% of French people have a favorable view of Russia, with 62% expressing an unfavorable view.[188] In return numerous French scholars and politics argue that France had a longstanding positive opinion about Russia and regret that France from the late 2000s tends to follow American positions against Russia blindly.[189][original research?]

United Kingdom

Though Anglo-Russian relations were traditionally warm from the 16th to the 18th century, by the beginning of the 19th century Russophobia started to appear in the media.[190] Depictions of Russia by British travel writers and newspaper correspondents described the country "as a semi-barbaric and despotic country", an image which ingrained itself in the British public consciousness as such depictions were frequently published in the British media; these depictions had the effect of increasing Russophobia in Britain despite growing economic and political ties between the two countries.[191] The Russian conquest of Central Asia was perceived in Britain as being a precursor to an attack on British India and led to the "Great Game", while the Crimean War between the two countries in 1853–1856 deepened Russophobia in Britain.[192][page needed]

In 1874, tension lessened as Queen Victoria's second son Prince Alfred married Tsar Alexander II's only daughter Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna, followed by a state visit to Britain by the tsar. The goodwill lasted no more than three years, when structural forces again pushed the two nations to the verge of war, leading to a re-emergence of Russophobia in Britain.[193] Large outbursts of Russophobia in Britain typically occurred during periods of tense political standoffs, such as the 1904 Dogger Bank incident, when the Baltic Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy attacked a group of British fishing trawlers in the mistaken belief they were Japanese warships; outrage in Britain led to the Russian government paying compensation to the fishermen involved.[194]

British Russophobia also manifested itself in popular literature of the period; Bram Stoker's Dracula has been seen by some historians as depicting an allegorical narrative in which the eponymous character (representing Imperial Russia) is "destroyed by warriors pledged to the Crown."[192][page needed] However, by the tail end of the 19th century, Russophobia in Britain subsided somewhat as Russian literature, including works written by authors such as Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky began to gain a level of popularity in Britain; positive views of the Russian peasantry also started to appear in British writing during this period.[195]

A May 2021 YouGov poll had 73% of British respondents expressing an unfavourable view of Russia, with no other country more negatively viewed in the UK except for Iran at 74% unfavourability.[196] Russian people in the UK, however, generally didn't encounter harassment or infringement of their rights based on nationality or ethnicity until 2022.[197]

Some Russians in the UK have reported experiences of local hostility after Russia's invasion of Ukraine.[198] Conservative MP Roger Gale called for all Russian nationals to be expelled from the country.[199] Gale acknowledged that most Russians in the UK were not a threat to national security, he believed it was necessary to "send a very harsh message through the Russian people to Putin."[200] MP Tom Tugendhat also suggested in one occasion that Russian citizens should be expelled from the country.[201][202][200] Evgeny Lebedev, a Russian-born British businessman, claimed that businesses and institutions declined to collaborate with the Evening Standard newspaper, which he owns, amid the war in Ukraine, citing anti-Russian sentiment.[203] Poole-born Alexandra Tolstoy had her account closed by NatWest, which she suspected to have happened because of her Russian name.[204][205]

North America

A National Hockey League agent who works with most of the Russian and Belarusian players in the league has claimed that since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, many of his clients have faced extreme harassment because of their nationality and high prominence, including xenophobia and death threats, as have those Russians and Belarusians who play in other professional North American leagues.[206][207]

Canada

In February 2022, a Russian Orthodox Church in Calgary was vandalized with red paint.[208][209] On 4 March 2022, a parish of the Russian Orthodox Church in Victoria, British Columbia was painted blood red by vandals, possibly in response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[210][211] The next day, the colours of the Ukrainian flag were spray painted on the doors of a Vancouver Russian Community Centre.[212][213] The Calgary Police Service announced in March they were investigating reports of anti-Russia hate speech and harassment on social media.[214][215][216][217]

In October 2022, numerous threats were made towards individuals affiliated with a Russian Orthodox Church in Calgary.[218] Police stated, "As it is believed the church was targeted because of its Russian heritage, this incident has been deemed a hate-motivated crime".[219] Around the same time Calgary police received several other reports related to threats and harassment of Russian Calgarians which they believe are related. An individual has been located and charged with multiple counts of hate-motivated criminal harassment. A representative of the Calgary police stated, "We would like to make it clear that hate-motivated crimes of any kind will not be tolerated in our city."[219][217][220]

United States

After friendly relations from the United States' founding in 1776 to the mid-19th century, Americans' view of Russia gradually deteriorated by the 1880s because of pogroms as well as the monarchical system.[221] Relations with the Russian Communist government had been highly hostile ever since the Bolshevik coup in 1917 and their subsequent crackdown on all opposition and the state-sponsored Red Terror.[222] The United States recognized Soviet Russia only in 1933 under the Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the countries were allies against Germany in World War II.[223]

Relations quickly turned hostile again in 1945–1947, after the war ended, and remained so during the Cold War years, 1947–1989. The Soviet Union's aggressive and increasingly militaristic foreign policy that led to their takeover of Eastern Europe and establishment of a network of satellite states, known as the Soviet Bloc,[224] as well as totalitarian rule at home that was accompanied by political repression and persecution of dissidents.[222] However, Americans often conflated the terms "Russians" and "Communists"/"Soviets". To stop that in 1973 a group of Russian immigrants in the US founded the Congress of Russian Americans with the purpose of drawing a clear distinction between Russian national identity and Soviet ideology, and preventing the formation of anti-Russian sentiment on the basis of anti-communism.[225] Members of the Congress see the conflation itself as Russophobic, believing "Russians were the first and foremost victim of Communism".[226]

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the collapse of Communism, anti-Russian sentiment in the United States was at an all-time low. 62% of Americans expressed a positive view of Russia in 1991 and only 25% viewed the country negatively. In 1997, 66% of Americans indicated their friendliness to Russia.[227] However, Russophobia has experienced a resurgence during the late 1990s due to Russia's opposition to the enlargement of NATO. According to a Gallup poll, 59% of surveyed Americans viewed Russia negatively in 1999, compared to only 25% in 1991.[45] Still, as relations recovered after the September 11 attacks, and Russia's support for the United States, favorability ratings of Russia again rose to 66% in 2002.[227]

Recent events (since 2012) such as the Anti-Magnitsky bill,[228] the Boston Marathon bombing,[229] annexation of Crimea,[15] the Syrian Civil War, the allegations of Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections,[230] the mistreatment of LGBT people in Russia following the passage of a 2013 anti-LGBT propaganda law in the country, and the seizure and destruction of banned Western food imports in Russia starting in August 2015[231] are many examples of events which have been deemed[according to whom?] to have caused a rising negative attitude toward Russia in the United States.[citation needed]

In 2013, the formerly majority positive view of Russia among American respondents critically declined and this perception was replaced by a majority negative view of 60% by 2014. By 2019, a record 73% of Americans had a negative opinion of Russia as a country, and formerly dominant positive opinions had fallen from 66% down to 24%. In 2019, the share of Americans considering Russia to be a "critical" threat to national security reached a majority of 52% for the first time.[232]

2001 to Russian reset

In 2005, scholars Ira Straus and Edward Lozansky described negative coverage of Russia in mainstream American media, contrasting sentiment in media coverage with largely positive sentiment of the American public and U.S. government.[233][234]

The 2008 Russo-Georgian War was one of the recent events that contributed to growth of the negative sentiment toward Russia by the U.S. government. However, in 2011 the majority of American respondents still viewed Russia favorably.[227] According to researchers Oksan Bayulgen and Ekim Arbatli, whose content analysis of the coverage of the events in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal indicated presence of anti-Russian framing bias, people who followed the news more closely had a more negative opinion of Russia than those who rarely followed the conflict. They describe the politicization of foreign policy in the 2008 United States presidential election debates, concurrence of which with the Russo-Georgian War "made Russia a part of the national political conversation". They also suggest that the links between media, public opinion and foreign policy exist, where U.S. media had an important role in sustaining the Cold War mentality and anti-Russian public sentiment.[14]

End of Russian reset to present

According to surveys by Pew Research Center, favorable views of Russia in the United States started to decrease after reaching their peak in 2011, reducing from 51% to 37% by 2013.[16] In a 2013 survey, 60% of Americans said the United States could not trust Russia.[235] Additionally, 59% of Americans had a negative view of Russia, 23% had a favorable opinion, and 18% were uncertain.[236] According to a survey by Pew Research Center, negative attitudes towards Russia in the United States rose from 43% to 72% from 2013 to 2014.[15]

Whereas in 2006 only 1% of Americans listed Russia as "America's worst enemy", by 2019 32% of Americans, including a plurality of 44% of Democrats, shared this view,[232] with a partisan split having emerged during the 2016 presidential campaign. The sharper distaste among the Democrat population stands in contrast to the prior history of American public opinion on Russia, as Republicans were formerly more likely to view Russia as a greater threat.[237]

In May 2017, former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper stated on NBC's Meet the Press that Russians are "almost genetically driven" to act deviously.[238][239] Freelance journalist Michael Sainato criticized the remark as xenophobic.[240] In June 2017, Clapper said that "[t]he Russians are not our friends", because it is in their "genes to be opposed, diametrically opposed, to the United States and Western democracies."[241] Yuliya Komska in The Washington Post took note of a Russiagate-awareness media project featuring Morgan Freeman and James Clapper and wrote that its "hawkish tenor stokes blanket Russophobia that is as questionable as the Russian state media's all-out anti-Americanism."[242]

In June 2020, Russian American professor Nina L. Khrushcheva wrote: "Normally, I would not side with the Kremlin. But I cannot help wondering whether the Russophobia found in some segments of America's political class and media has become pathological."[243] In July 2020, academic and former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul spoke about "combatting Russophobia", appealing to U.S. officials and journalists to cease "demonizing" Russian people, and criticizing propagation of stereotypes about Russians, Russian culture and Russian national proclivities.[244] He, and some other commentators, have argued that the U.S. media does not make enough distinction between Putin's government and Russia and the Russians, thus effectively vilifying the whole nation.[245][246]

On July 2, 2020, the Lincoln Project, a group of anti-Trump Republicans,[247] released Fellow Traveler, an ad saying in Russian with English subtitles that "Comrade Trump" had been "chosen" by Vladimir Putin and had "accepted the help of Mother Russia." The ad featured communist imagery such as the hammer and sickle, as well as photographs and imagery of Bolshevik dictators Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, and Mikhail Gorbachev. Eliot Borenstein, Professor of Russian and Slavic Studies at NYU, criticized the Lincoln Project's "Russophobic" ad, saying: "How would we feel about a two-minute video filled with Stars of David, men in Orthodox garb, sinister snapshots of Bibi, and soldiers in tanks, all to the tune of “Hava Nagila”? If that doesn't make you uncomfortable, I'm not sure what to tell you."[248]

The Wall Street Journal argued in an editorial that the White House blamed Russia for the 2021–2022 inflation surge to deflect criticism of the domestic economic policies.[249]

Hollywood and video games

Russians and Russian Americans are usually portrayed as ruthless agents, brutal mobsters, psychopaths, and villains in Hollywood movies[250][251][252] and video games. In a 2014 news story, Fox News reported that "Russians may also be unimpressed with Hollywood's apparent negative stereotyping of [the Russian people] in movies. The Avengers featured a ruthless former KGB agent, Iron Man 2 centers on a rogue Russian scientist with a vendetta, and action thriller Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit saw Kenneth Branagh play an archetypal Russian bad guy, just to name a few. Some games in the critically-acclaimed Grand Theft Auto series depict Russians and the Russian Mafia they are supposedly part of as ruthless and heavily-armed enemies which the player has to fight against as part of the storyline, particularly Grand Theft Auto IV which features a Russian mobster named Dimitri Rascalov as its primary antagonist.[253][254][255][256][257]

The video game Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 portrays Russian soldiers as over-the-top villains and contains a controversial mission titled "No Russian", which involves the player engaging in a mass shooting in a Russian airport. In Russia, the game sparked calls for boycotts and prompted live streamers to pull out of deals with publisher Activision, with Russians also flooding Metacritic online to vote down the game's user score.[258]

Pacific

New Zealand

Russophobia in New Zealand dates back to the colonial era; early anti-Russian sentiment among New Zealanders was influenced by "the general Victorian dislike of Tsarist autocracy" and British immigrants to the colony who brought "with them the high level of anti-Russian sentiment at home." Polish, Hungarian and Jewish refugees fleeing Russia's suppression of various rebellions and outbreaks of anti-Jewish pogroms also influenced Russophobia in New Zealand. In the aftermath of the Crimean War, suspicion of a possible Russian invasion of New Zealand led the colonial government to construct a series of "Russian-scare" coastal fortifications along the coastline. However, during the First World War, anti-Russian sentiment subsided as New Zealand and Russia found themselves fighting on the same side against Imperial Germany and anti-German sentiment grew in its place. By late 1920s pragmatism moderated anti-Russian sentiment in official circles, especially during the Great Depression. Influential visitors to the Soviet Union, such as George Bernard Shaw, provided a sympathetic view of what they experienced.[259] The history of Russophobia in New Zealand was analyzed in Glynn Barratt's book Russophobia in New Zealand, 1838–1908,[260] expanded to cover the period up to 1939 in an article by Tony Wilson.[259]

Asia and Middle East

Iran

16th-18th centuries

Anti-Russian sentiment in Iran dates back centuries. The modern historian Rudi Matthee explains that already by the Safavid period (1501-1736), the Iranians "had long despised Russians for their uncouthness".[261] Russians enjoyed a bad reputation in Iran, where, by the 17th century, they were known as the Uzbegs of Europe, the worst of all Christians, unmannered, unintelligent and perpetually intoxicated.[262] This perception can be traced back to ancient Greco-Roman cosmographical conceptions which had been conveyed to the Islamic world. According to this concept, the world was divided into seven climes; the farther away the concentric clime from the center, the more barbarian its inhabitants were deemed. The notion was also connected to the old concept of Gog and Magog as found in the Quran, according to which, beyond this boundary lay a murky land inhabited by dimwitted people.[262] Hence, describing this stereotype, in written Safavid sources the denigratory adjective rus-e manhus ("inauspicious Russia" or "ominous Russia") was coined.[262][263] Over time, it became a generic term for Iranians referring to Russians.[262]

By the mid-17th century, the term rus-e manhus designated Cossacks in particular who created havoc around the Caspian littoral, and whom the Iranians did not really distinguish from "real" Russians. By the 18th century, according to Matthee "stereotypes about a primitive people more given to act out of instinct than reason are also likely to have been reinforced by the fact that Iranians, in Jonas Hanway’s words, probably did not see more of “Russians” than tribal, nomadic peoples living around the Caspian Sea, and of “real” Russians at most uncouth soldiers and illiterate fishermen."[262] However, contemporaneous Iranians were probably no less prone to view Russians as primitive and uncivilized than contemporary English commentators were.[264]

Due to said perceptions, 17th-century Russian envoys were treated with occasional rudeness by the Iranians. Most of the mistreatment of said envoys was however grounded in suspicion and resentment about possible hidden objectives and designs by the Russians. However this was a common global view at the time regarding envoys. Envoys and emissaries were basically invariably seen as having (secret) motives and being spies. In fact, it was this very view that prevented the establishment of permanent diplomatic missions in Europe in the early modern period.[264] Iranian suspicions in the mid-17th century about Russian motives were nevertheless longstanding, ran deep amongst the populace, and were based on genuine concerns.[265]

At the time, the Russians tried to present profitable commercial missions as diplomatic embassies, and covertly tried to support Cossack attacks on Iran. The construction of fortresses in the Caucasus however was the most important factor at the time (see also; Russo-Persian War (1651-1653), with Iranian concerns about Russian plans to subjugate the Caucasus dating back to the mid-16th century. With the rise of the Tsarist realm of Peter the Great and his aggression against Iran in the first half of the 18th century, such concerns were quickly reinvigorated, and were ultimately prophetic in view of the later Russian annexation of the Caucasus in the course of the 19th century.[265]

In the course of the 18th century Iranian views of Russians were somewhat adjusted, due to Peter the Great's modernization efforts and expansionism as initiated by Catherine the Great. However, Iranian views of their northern neighbors as being somewhat bland and primitive were apparently never relinquished.[264]

19th-21st centuries

In his book Iran at War: Interactions with the Modern World and the Struggle with Imperial Russia, focusing on the two Russo-Iranian Wars of the first half of the 19th century (1804-1813, 1826-1828), the historian Maziar Behrooz explains that Iranian and Russian elites held a demeaning view of each other prior to the reunification campaigns of Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar (r. 1789–1797), as well as through the early 19th century.[263] They viewed each other as uncivilized and backwards, and thus held each other in contempt.[263] For instance, the most commonly used contemporaneous denigratory adjective in Iran for Russians was the aforementioned adjective rus-e manhus.[263] The contemporaneous British diplomat, traveller and novelist James Justinian Morier, writing in 1808, noted that the Iranians spoke of Russians with the greatest disdain.[266] As a result of aforementioned wars, Russia annexed large parts of Iranian territory in the Caucasus; With the Treaty of Gulistan (1813) and Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), Iran was forced to cede what is present-day Azerbaijan, Armenia, eastern Georgia and southern Dagestan to Russia.[267] This fuelled anti-Russian sentiment which led to an angry mob storming the Russian embassy in Tehran and killing everyone in 1829. Among those killed in the massacre was the newly appointed Russian ambassador to Iran, Alexander Griboyedov, a celebrated playwright. Griboyedov had previously played an active role in negotiating the terms of the treaty of 1828.[268][269]

Soviet involvement in the Azerbaijani and Kurdish separatist movements also fueled negative attitudes.[270] In 2009, negative attitudes to Russia among the Iranian opposition was also observed due to Russian support of the Iranian government.[271] A September 2021 poll done by the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland had 42% of Iranian respondents holding an unfavourable view of Russia compared to 56% holding a favourable view.[272]

India

Russian visitors to Goa make up one of the largest groups in the state and according to Indian media, there has been tension between them and the locals due to violence and other illegal activities committed by some visitors.[273][274][275] In February 2012, Indian politician Shantaram Naik accused Russians (as well as Israelis) of occupying certain coastal villages in Goa.[276] In August 2012, Indian politician Eduardo Faleiro rejected the Russian consul general's claim that there was no existence of the Russian mafia there, alleging "a virtual cultural invasion" was occurring in Morjim.[277] According to the Indian Express in 2013, Goan resentment of foreigners had been building, with anger particularly directed towards Russians and Nigerians.[278]

In 2014, after Goan taxi drivers protested against Russian tour operators allegedly snatching tourist transport services from them, Goa's ministry of tourism cancelled an Indo-Russian music festival, sparking criticism from a few Russian diplomats.[279] In 2015, the Russian information centre reportedly said India and Goa "were not considered as good destinations for Russian travellers".[280][281]

Japan

Many Japanese interactions with Russians as of 2009 occurred with seamen and fishermen of the Russian fishing fleet, therefore some Japanese carried negative stereotypes associated with sailors over to Russians.[282][283][284]

According to a 2012 Pew Global Attitudes Project survey, 72% of Japanese people view Russia unfavorably, compared with 22% who viewed it favorably, making Japan the most anti-Russian country surveyed.[285] A 2017 poll from the Japanese government found that 78.1% of Japanese said they felt little or no affinity to Russia, which was the second highest percentage out of 8 regions polled (behind China at 78.5%).[286]

In December 2016, protesters gathered in Tokyo demanding the return of islands in the Kuril Islands dispute.[287]

Instances of harassment, hate speech and discrimination targeting Russians living in Japan were reported after 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi condemned human rights abuses against Russians that took place.[288]

Kazakhstan

According to the Jamestown Foundation, while previously not known for being anti-Russian, Kazakhstan since independence has grown increasingly hostile to both Russia and China. Russian commentator Yaroslav Razumov alleges that "anti-Russian articles are a staple of the Kazakh media".[289] Recently, Kazakh nationalists have criticized people who prefer speaking in Russian than Kazakh despite being one of the two official languages in the country.[290] In 2014, ethnic Kazakhs were enraged with the statement of Russian president Vladimir Putin that "Kazakhs never had any statehood" before independence.[291][292]

China

Tensions between Russia and China began with the Sino-Russian border conflicts, which began in 1652 and lasted until 1689.[293] During the 19th century, when the Qing dynasty of China was distracted suppressing the Taiping Rebellion and fighting the Second Opium War, the Russian government annexed the region of Outer Manchuria through the Unequal Treaties of late imperial China.[294] Russia would continue to sponsor various groups, both pro and anti-Chinese, helping to destabilize China with the Dungan rebellion and Russian occupation of Ili.[295] Towards the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Russia invaded Manchuria and was among a major participant that crushed the Boxer Rebellion against European powers.[296][297]

With the collapse of the Tsarist Empire in Russia, the Soviet Union was founded. Nonetheless, tensions between the USSR and China remained high. The Soviet Union waged the 1929 war against China, which ended in Soviet victory.[298] The Soviet Union would continue following Imperial Russia's expansion of influence by sponsoring a number of various militia groups destabilizing China, especially in Xinjiang which resulted in the Kumul Rebellion, Soviet invasion of Xinjiang and followed by the Islamic rebellion and Ili Rebellion in 1937 and 1944.[299] The Soviet invasion and occupation of Manchuria in 1945 following Japanese control increased anti-Russian and anti-Soviet sentiment as a result of war crimes committed by Soviet troops, including rape and looting.[300][301][302][303][304][305]

Nowadays however, anti-Russian sentiment in China has greatly downgraded, due to perceived common anti-Western sentiment among Russian and Chinese nationalists.[306][307] Ethnic Russians are one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People's Republic of China.[308]

South Korea

A 2020 Gallup International poll had 75% of South Koreans viewing Russia's foreign policy as destabilizing to the world, which was the third highest percentage out of 44 countries surveyed.[309][310] A Morning Consult poll finished on February 6, 2022, had South Korean respondents holding a more unfavorable than favorable impression of Russia by a difference of 25% (the second highest percentage in the Far East).[311] Anti-Russia protests against the country's invasion of Ukraine were held in Seoul and Gwangju,[312] with one also planned in Busan.[313]

Turkey

According to a 2013 survey, 73% of Turks viewed Russia unfavorably against 16% with favorable views.[314] A 2011 SETA poll had 51.7% of Turks expressing a negative opinion of Russians compared to 20.7% expressing a positive opinion.[315] According to a 2012 report, hoteliers in Antalya viewed Russian tourists more negatively than tourists from the West.[316]

Historically, Russia and Turkey fought several wars and had caused great devastation for each nation. During the old Tsardom of Russia, the Ottomans often raided and attacked Russian villagers. With the transformation into Russian Empire, Russia started to expand and clashed heavily with the Turks; which Russia often won more than lost, and reduced the Ottoman Empire heavily. The series of wars had manifested the ideas among the Turks that Russia wanted to turn Turkey into a vassal state, leading to a high level of Russophobia in Turkey.[317] In the 20th century, anti-Russian sentiment in Turkey was so great that the Russians refused to allow a Turkish military attache to accompany their armies.[318] After the World War I, both Ottoman and Russian Empires collapsed, and two nations went on plagued by their civil wars; during that time Soviet Russia (who would later become Soviet Union) supported Turkish Independence Movement led by Mustafa Kemal, leading to a warmer relations between two states, as newly established Turkish Republic maintained a formal tie with the Soviet Union.[319] But their warm relations didn't last long; after the World War II, the Bosphorus crisis occurred at 1946 due to Joseph Stalin's demand for a complete Soviet control of the straits led to resurgence of Russophobia in Turkey.[320]

Anti-Russian sentiment started to increase again since 2011, following the event of the Syrian Civil War. Russia supports the Government of Bashar al-Assad, while Turkey supports the Free Syrian Army and had many times announced their intentions to overthrow Assad, once again strained the relations.[321] Relations between the two went further downhill after a Russian jet was shot down by a Turkish jet,[322] flaring that Russia wanted to invade Turkey over Assad's demand; and different interests in Syria. Turkish media have promoted Russophobic news about Russian ambitions in Syria, and this has been the turning point of remaining poor relations although two nations have tried to re-approach their differences. Turkish military operations in Syria against Russia and Assad-backed forces also damage the relations deeply.[323]

Business

On 27 July 2006, The New York Times quoted the analysts as saying that many Western investors still think that anything to do with Russia is "a little bit doubtful and dubious" while others look at Russia in "comic book terms, as mysterious and mafia-run."[324]

See also

- Death of Alexei Navalny

- Allegations of genocide in Donbas

- Allegations of genocide of Ukrainians in the Russo-Ukrainian War

- Anti-Slavic sentiment

- Anti-Sovietism

- Atrocity crimes during the Russo-Ukrainian War

- Crimes against humanity

- German atrocities committed against Soviet prisoners of war

- Great Russian chauvinism

- International reactions to the war in Donbas

- Rashism

- Reactions to the Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Russian filtration camps for Ukrainians

- Russian war crimes

- Russo-Ukrainian War

- Sexual violence in the Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Torture

- War crimes in the Russian invasion of Ukraine

References

- ^ McNally, Raymond T. (1958). "The Origins of Russophobia in France: 1812-1830". Slavic Review. 17 (2): 173–189. doi:10.2307/3004165. ISSN 1049-7544. JSTOR 3004165.

- ^ Williams, Robert C. (1966). "Russians in Germany: 1900-1914". Journal of Contemporary History. 1 (4): 121–149. doi:10.1177/002200946600100405. JSTOR 259894. S2CID 154477120.

- ^ Brook, Tom (5 November 2014). "Hollywood stereotypes: Why are Russians the bad guys". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ "Submission to the United States Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination". Human Rights Documents Online. doi:10.1163/2210-7975_hrd-9211-20180082.

- ^ Macgilchrist, Felicitas (21 January 2009). "Framing Russia: The construction of Russia and Chechnya in the western media". Europa-Universitat Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder). Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2015.